In the micro-universe of the village, history is made up of gardens, houses, and objects passed down from generations. These cherished objects house family stories and histories. Histories doomed to disappear when no one is left to preserve them. They are all tangible and intangible traces of our journey through the world. It naturally begs the question: how can we fight against oblivion? How do we define “home” in a dynamic, fluid, ever-changing social and economic context?

Imagine closing your eyes, and for a few moments, you could envision your childhood home. What would be the first things that would come to mind? You’d perhaps see the front door and stairs. A tablecloth and plates of dishes. Maybe you’d see a roof or a hallway. Whatever the answer, the memory of the house we each grew up in remains almost physically engraved within us. The traces that the built space leaves on memory are what anthropologist Gaston Bachelard calls the poetics of inhabited space.[1] The exhibition Harvest Time by artist Ioana Sisea and curated by Anca Verona Mihuleț and Iris Ordean represents an exercise of returning to the image of the house as a mental construct. It represents the house as memory – subject to degradation, change, and transformation.

Presented at Kunsthalle Bega starting September 2nd 2022, the exhibition consists of two parts: an art installation and a short documentary film. The installation reveals itself in layers, being made of multi-colored walls of tens of thousands of beads tied into strings without a start or an end point. The installation covers the entire surface of the room so that as a visitor you become part of it, you can examine it, touch it and look at it closely. The work begins to take on a much deeper meaning when you discover that what you are seeing is literally the childhood home of the artist’s grandparents. Through a meticulous process that took five years, the objects were thus melted, made into fretwork, and cut into bead shapes. Chairs, beds, carpets, household appliances, bills, newspapers, mugs, and glasses. Silver-plated cutlery for special occasions and Sunday clothes. All became one and the same through an almost alchemical process of preservation and recycling. Room by room, material by material, object by object.

“I wanted to keep the house without keeping the house,” says the artist in an interview with Igloo magazine.[2]

In this way of interpretation, the work becomes in a literal sense the materialization of the reverberation of a once-inhabited space. The work process itself is thus completed by the memory of domestic activities around the house, from the care and cleaning of the space to the agricultural routines that require sustained physical labor daily. In fact, the title is a reference to the tradition present in south-eastern Europe of drying fruit and vegetables in autumn and hanging them up on the walls of the house or from the ceiling. The link between the way the installation is represented and traditional agricultural activities is a reference to processes involving physical labor, both in art and in everyday life.

From a socio-economic point of view, abandoned houses are no longer of immediate use, and they end up decaying to the point of destruction or being sold. The past generations of grandparents and great-grandparents looked at their homes as a source of personal identity and a context of history lived together. When the place becomes a tradable commodity on the real estate market, it loses some of its existential meaning, as Sarah Robinson points out in the book Nesting: Body, Dwelling, Mind. Sarah Robinson provides a study of the many ways in which our built environment shapes us just as we shape it. The author describes how the still-existing search for the ideal ‘home’ is strongly influenced by the status of the home as a commodity and by the consequence of the freedom of delocalization:

“Our environment mirrors what we have come to believe about our relations and ourselves: that all are re-place-able […] Dislocated from the tissue of community, people are routinely forced to start tabula rasa […]”[3]

Therefore, the installation consciously or unconsciously becomes a symptom of this phenomenon. In fact, the autobiographical aspect and the triggering point of the artist’s approach is the house in a village near Giurgiu, passed on to her with the death of her grandparents. The objects became perishable goods and were consequently stripped of their value once they were taken out of the context of living and village life. The objects became perishable goods and were consequently stripped of their value once they were taken out of the context of living and village life. The work thus wrests them from the sale-purchase circuit that is predestined for any object.

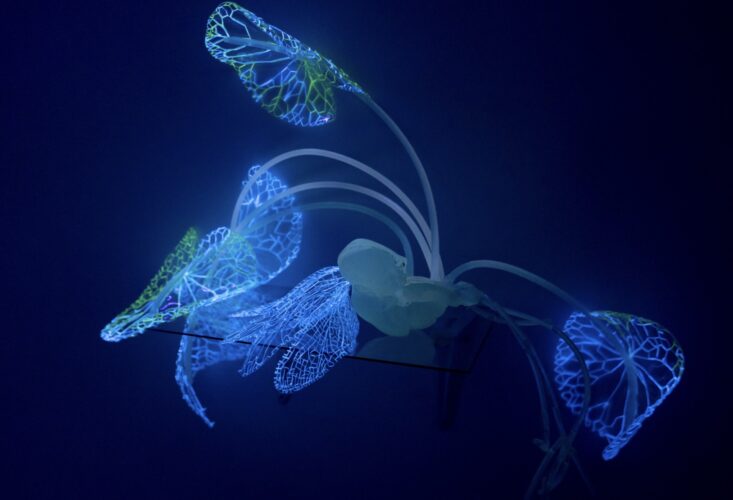

It is interesting to note that, during the same period in which Harvest Time took place, another exhibition presented in Timișoara at META Spațiu by the artist Andreea Medar focused on the topic of the childhood home. Solarium. The Forever Garden, curated by Mălina Ionescu, is based on an autobiographical thread: the village house of the artist’s grandparents and the garden that was abandoned after the death of her grandfather. However, the exhibition clearly stands out from Harvest Time by the way it represents the space of the house and the discourse it suggests. Solarium. The Forever Garden depicts the childhood home in a futuristic dystopian universe where natural organic materials are replaced by plastic and silicone. The artist has recreated the house as a greenhouse in which fluorescent silicon plants are born and grow. An immersive installation that takes up the entire exhibition room.

The exhibition incorporates references to the practice of gardening and brims with plant imagery. Gardening is here understood through the lens of the tradition that the artist’s grandfather practiced from generation to generation, as well as a metaphor for the bond between generations and the preservation of one’s roots. How the artist has hand-stitched the greenhouse from plastic threads taken from solarium sheets is also a direct reference to the practice of rural women hand-weaving their clothing and other domestic objects. The exhibition talks about the need to preserve endangered practices and customs (such as gardening or sewing) as well as the importance of knowing your own family history to build your identity.

So, both exhibitions stem from the search for the past and the underlying relationship between the self and the childhood home, but they represent two distinct ways of understanding this relationship. Naturally, it begs the question: is the artistic recovery of the native domestic space a symptom of reclaiming the relationship between the self and the environment, a relationship increasingly dematerialized in the digital age? Is it a wake-up call to the fact that the old world is disappearing, and the new generation feels the need to fill the void that the past leaves behind by creating an imaginary link between generations?

The opposites that co-exist today at the level of identity continue to be reflected in the search for a timeless “home” on the one hand and the freedom of movement from one corner of the world, and the infinite possibilities of choosing what you want to become on the other.

Coming back to Harvest Time, the emotional experience you have as a viewer after exploring the installation is enhanced by the documentary film showing the house as it was entrusted to Ioana by her grandparents. Without a narrative line, the shots show you a domestic world that you know has no real counterpart. The camera enters every room, where every object is revealed as it was originally: the floral bedspreads on the bed, the tablecloths, the kitchen cupboards, the TV with white doily, the framed Gobelin tapestries on the wall, the wardrobe with Avril Lavigne and Titanic stickers on the doors.

Simple objects of home décor denote layers of deep-rooted feelings, thoughts, and behaviors from the perspective of personal memory. You look at the house, and you feel that you are looking at a familiar place, a place that could be yours. You recognize fragments of familiar material culture and, so, recognize a part of your past.

Through the discourse it proposes, Harvest Time is not a nostalgic approach to home understood as a lost paradise. It represents the deconstruction of an idealized image of the personal past and proposes possible ways to understand the status of an object from a commercial good that goes out of fashion with time to a memory that has the power to reverberate. It is an approach that answers the question: “How can we fight against oblivion?”

[1] Gaston Bachelard, The poetics of space, edit. Beacon Press Books, Boston, 1994

[2] https://www.igloo.ro/harvest-time-sau-conservarea-prin-distrugere-interviu-cu-artista-ioana-sisea/

[3] Sarah Robinson, Nesting: Body, Dwelling, Mind, edit. William Scout Publishers, 2011

Translated by Camelia Diaconu

POSTED BY

Ioana Gabriela Cherciu

Ioana Gabriela Cherciu ( n.1995) a absolvit Facultatea de Filosofie, urmând apoi un master în studii culturale la Centrul de Excelență în Studiul Imaginii. Practica ei se concentrează pe documen...

Comments are closed here.