About 20 people, sitting in a circle, pass each other notes where each writes a solution for a person’s difficult emotional issue (how would you tell, if you were to tell, your significant other that you had an affair): a guy, the performer, Cristi Gheorghe. None of us knows what the others wrote until the notes go full circle. As the notes pass from person to person and Cristi Gheorghe’s story unfolds, one thing is clear: he never uses gender pronouns when talking about the people in his love life; his “monologue” is meant to be “gender-blind” (and that is no easy task in the Romanian language, that’s why it really stands out; in Eugen Jebeleanu’s monologue, written in Neil LaBute’s drama workshop – a monologue that eventually turned into the show Why not do it in the middle of the road – he states that avoiding masculine and feminine pronouns is a real feat of strength. But the public’s written answers obviously ignore this ambiguity where any gender combination (girlfriend/boyfriend/mistress/lover) is possible. What appears to be a teenage (or Facebook) game quickly becomes an excursion into the hetero-normative imaginarium – in their overwhelming majority, the spectators/participants were deconstructing and reconstructing the situation in various versions of types of homosexual relationships.

At the beginning of summer, WASP studios presented the conclusion of an action-performance workshop by Ioana Păun, where artists were meant to “willingly position themselves in highly risky personal, professional, political or ethical situations”. Ioana Păun, who studied theater directing, has worked a lot with performance art, especially with themes concerning domestic labor and immigrants who work as nannies or maids (in Romania, Itally, USA, Austria).

Most of the participants (eight out of six, to be exact – everyone except Răzvan Dutchevici, who studied audio-visual communication and works in film, and Corina Tărău, a competitive dance champion) had a background in theater – some of them are actors, while others (Selma Dragoș) are directors – generally speaking, they all had previous performative experiences (as in they were familiar with the stage). It is really interesting to see performance into play, especially for the actors (I admit, for someone who knows a few things about their training system, as opposed to an “naive” spectator, it is easy to retrace an actor’s steps within a workshop by judging the final work), because, paradoxically, nothing seems more open to this intimate “truth” while at the same time strongly opposing any type of direct contact with the audience and owning up to this “truth”, than the Romanian acting method. “Myself in this situation” – the magical phrase that is used in training every actor to relate to a fictional situation through their own inwardness, affective memory, personal life experiences – is able to build an entire structure that is meant to protect the actor from identifying and personally owning up to that situation. It is a make-believe that pushes realism to the borders of the actor’s own values and beliefs – just beyond the point where the performative action begins. This is evident in the workshop’s title – it’s less about the specific types of performance art structures and more about building an instrument for losing inhibition: “getting on stage” (this phrase says it all: there is less need to get on stage nowadays, but our entire vocabulary is based on the realist theater convention, where the stage is everything) and talking about the most delicate moments of your life and your most intimate beliefs – and you don’t get to transfer them onto a character.

The public’s involvement in each performance varied – the space which hosted the actions was a decisive element: a black box, a theatre stage with the viewers sitting quietly in their amphitheatre seats, with frontal vision, meaning that the forth wall could easily be broken. For example, Corina Tărău’s performance, What can you do when you can’t do what you’ve been doing since forever (7 minutes), a sort of free improve based on a given situation – that moment of “free time” when the young lady that has been training for dance competitions ever since she was a little girl suddenly finds herself torn from her work routine, a job and a sense of purpose -, was a very intimate look (due to its approach), from the sidelines, into “a slice” of undramatised loneliness and unhappiness that makes the spectator fell completely powerless.

The general interaction between the performers and the public was via direct addressing – either verbally (Selma Dragoș asked each of us if we were happy), visually (Simona Cuciurianu, Alec Secăreanu, Cristina Găvruș), or by mobilising the public, through emulation, into a collective action (Răzvan Dutchevici). All the while, Ruxandra Hule’s The woman was created from Adam’s rib (10 minutes) came close to a happening because of its construct and direct (non)relation to the public: the elegantly dressed and sexy performer uses a moulding paste (red, in contrast with the black dress), a moulding profile and a meat grinder. She then proceeded to use the grinder on a penis.

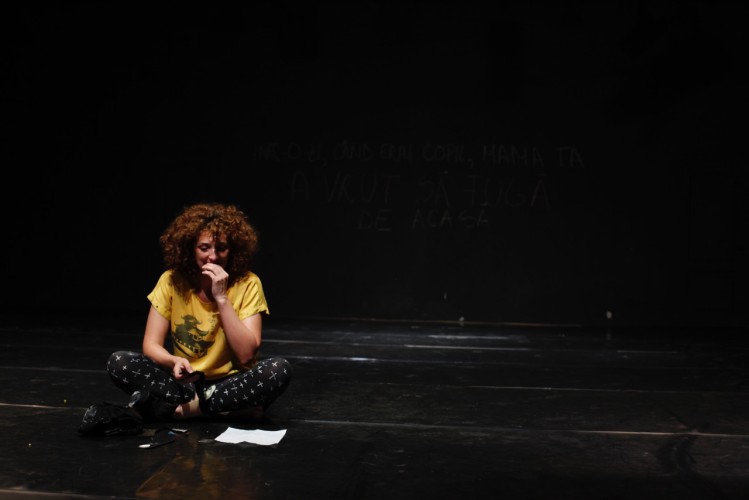

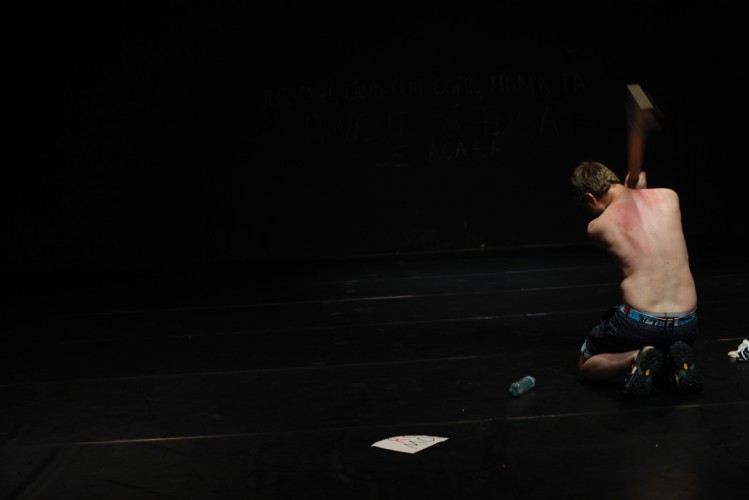

Cristi Gheorghe’s work, Once upon a time… (12 minutes), where we all passed notes to each other about what to do when you cheated on the partner you actually love, was the only participative performance – but, precisely because of this, it was also the least confrontational. The relation between exposure and protection is very carefully balanced (the level of personal exposure was split between the performer and spectators). In fact, Once upon a time… and Mother, only the mother by Selma Dragoș (8 minutes) were the two pieces that involved less immediate physical action (as opposed to the call to solidarity by making noise with bottles and rocks, followed by a solitary self-flagellation by Răzvan Dutchevici in United we can save, or the making of a molotov cocktail by using the Romanian flag as a wick in We are Orthodox Christians. The majority rules by Simona Cuciurianu) and more well performed stage drama. Mother, only the mother can qualify as a theatrical monologue in which the theme itself establishes the nature of the performance: a mother’s moments of meltdown and her inevitable desire to flee, at least for a short while, and leave the house and the maternal responsibly behind (it’s interesting to see that the performer avoided using the first person and opted for a diagonal performative identification: “mother Selma” empties the contents of her own bag and enumerates the objects that belong to her child).

It is clear that the WASP workshop wasn’t meant to produce performances, but to offer the artists the possibility of discovering their own mechanisms of non-traditionally working with their bodies and their personal and political preoccupations, thus profoundly exposing them and testing them in a safe space. It was worth it.

POSTED BY

Iulia Popovici

Iulia Popovici is a performing arts critic and curator. She is editor for the performing arts section at the Observator cultural weekly cultural magazine (Bucharest). She has written about the alterna...

Comments are closed here.