On artist-run spaces in Romania, with Dan Perjovschi, a conversation that is necessarily and inevitably uncomfortable at times about this segment of the art scene and the entire recent and current context.

Mălina Ionescu: Artist-run spaces and independent initiatives are an important part of the art scene, complementing the environment they operate in and making it more dynamic. At the same time, they are directly tied to its features. In Romania, their position relative to institutionalized art has existed, until very recently, between the poles of official and subversive art. Compared to the last three decades, how do independent spaces relate to cultural institutions today?

Dan Perjovschi: I think that, most often, artist-run spaces do more interesting things than established institutions. They’re more mobile, braver, and oftentimes more inventive than museums or galleries. That’s what need teaches you. My encounters with Atelier 35 Oradea, the Atlantic Center for the Arts Florida, Franklin Furnace New York, IBID Projects London, Schnittraum Köln, Isola Milano, Protokol Cluj, Prozori Zagreb, White Cuib Cluj, Salonul de proiecte, and 101 Bucharest have been essential.

Unfortunately not every such space in Romania is innovative. Or not all the time. Underfinancing and marginalization maintain things at the level of mere survival, which itself is no small feat. But it’s not what’s needed.

It is unclear what these spaces’ position is in Romania because scrambling for financing and dealing with stifling bureaucracy take up their time, energy, and drive. As does the lack of an international network. Some of them exhibit the same kind of projects (and artists) as state museums and private galleries. Romanian spaces are not critical per se, nor do they take a position relative to state institutions. They only try, and oftentimes succeed, to create things more professionally than state institutions and offer the kind of freedom that local art museums lack. This is how it’s like abroad too. I, for one, have oftentimes felt freer and better in a small independent space than at the Pompidou.

It’s true that the life of an artist-run space can be short. Some disappeared after their first project. Others are outgrowths of Art Safari. And some which were at one time radical now act like commercial galleries.

To me, our Romanian ones seem a bit too artistic… I don’t know how to put it.

Still, they’re all dear to me, and I think that here, in these “life or death” conditions of precarity, is where the most interesting practices develop.

It’s hard to define an independent space. Does independent mean non-profit? Is the UAP network independent? Is the Tranzit.ro network independent? What is a “cultural institution” in Romania? Is IDEA Magazine an institution? How about ARTA?

In Romania, municipal art museums are so (ultra) conservative that just driving a nail into a wall makes you radical.

I think we’re living in the age of hybridizations, where terms like state, independent, private, commercial, and non-profit mix with each other. Private galleries in Romania sometimes act like project spaces (if they’re not selling much anyway) and export artists onto the international scene, in museums and biennials, which the National Museum in the Palace of the Parliament or the Private Museum on Primăverii Street seem incapable of doing. Nonprofits exhibit at Liste Basel. Artist-run spaces have a dedicated section at Art Wien. The projects at Salonul de proiecte look more museum-like than anything exhibited in a museum. Some projects have long disappeared, while Lia’s CAA is over 30 years old at this point. Some spaces cling to public institutions, others to showrooms. Some make exhibitions, others edit books. At one point, contemporary dance was more radical (politically and formally speaking) than anything happening in the visual arts. Movies told things as they were. Now it’s all mixed up.

We all exhibit at the Venice Biennial.

What has changed since the 1990s? Independent projects and artist-run spaces have become more pragmatic. If at first there was only a wish to distance themselves from public institutions, stuck within their gilded frames, now there are intentions. Queer and permaculture. There is a minimal international network. We used to only be local. We used to compete with Baba. Now we also compete with Damien Hirst. What you make do with what you have depends on you and your philosophy…

Let’s not forget, Secession Vienna is an artist-run space…

M.I.: To return to the period before independently managing a space was possible, there were artist- or theorist-run initiatives that were seen as individual, even though they were part of the official system, like the programs of some museums, camps, or culture houses. After 1989 we see this kind of practice again – a recent example would be the MNȚR+C space in the National Museum of the Romanian Peasant (MNȚR). What do you think about this hybrid model?

D.P.: Well, let’s not mix things up. Sculpture camps gave the impression of great freedom, but have you ever seen a work there even metaphorically critical of the dictatorship? Or any to just honestly address the cows and sheep? Because, honestly, those were their only viewers. I know of no state museum programs under Communism that could have been called “independent,” or even interesting. Dictatorship and art don’t go together. The performances in the basement of the Sibiu Pharmacy Museum, various bolder actions from Atelier 35, the short period of relaxation between 1968 and 1971, the Rebreanu Salons in Bistrița, or the tents up in the mountains at Lake Saint Ann have become mythical in comparison to the official stiffness in the rest of the country.

First off, MȚR should only be called the Peasant Museum. We’re in 2022, for God’s sake! I wouldn’t get too excited. I doubt that MȚR “produces” the contemporary art shows it hosts, I don’t know if it has a budget for +C and, if it does, I doubt it’s decent. I doubt the museum’s carpenter will build the furniture for the independent project without visible distaste… I doubt there has been a public call for projects for that space. It’s likely based on personal, informal relations. And that creates dependence. Maybe I’m wrong. I haven’t seen enough. I don’t have enough data. Few independent projects are integrated into the philosophy of a state institution (listen to me, “philosophy”) or have a conceptual or critical relation to the space they operate in.

What does the Romanian peasant have to do with contemporary art?

What does the Parliament?

But, as I’ve said, and as you’ve said, hybrid projects that can make their own decisions and that, for a time, collaborate with or are hosted in public institutions are possible, see the Kinema Ikon room at the Art Museum in Arad. Except project rooms in museums (the basements where “young artists” exhibit) or photo-video departments at all of our art universities seem to me an excuse to not see the state of the rest of the museum (with paintings hanging by strings and a 19th century understanding of art) or the art school (with medieval princes made of plaster or Taschen paintings).

In other words, I’m afraid that if the museum hosting that decent space gets a new director, you can say goodbye to the space… it’s not part of the strategy or the vision, it’s rather something tolerated. But, again, maybe I’m wrong.

And yet, artists and curators need to “occupy” museums, libraries, and Romanian Cultural Institutes. The walls and the budgets belong to them.

M.I.: One of the most frequent kinds of spaces that are not so much managed by artists as open to experimentation has been that of the studio, and one of the most interesting and relevant studio-focused programs in Romania was the one you had in Casa Robescu in Bucharest together with Lia Perjovschi. Tell us a bit about that space, its projects, and the actions and interactions with students and artists.

D.P.: I think already on the third day we opened our studio as a space for debate. As soon as we got it, we were visited by a mail artist from Belgium we had exchanged letters with during the dictatorship. But we didn’t know what was mainstream and alternative, we didn’t know the anti-system and anti-market movements. From our perspective, everything beyond the Berlin Wall was compact, good, and free. That discussion from the summer of 1990 brought us back to earth. We had a lot to catch up with. And we couldn’t do it alone. So we had dozens of meetings.

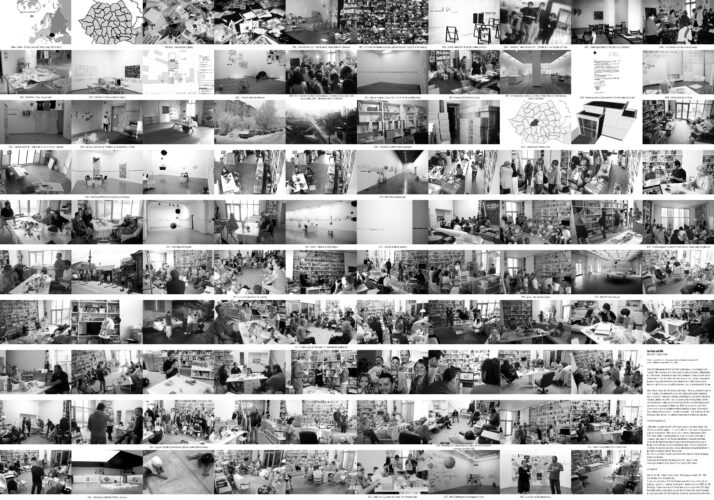

With a lot of people, one on one, with prepared topics, or informally… We had lectures by Mike Nelson, Roxana Marcoci & Cristian Alexa, and Claire Bishop and her students from the Curating Contemporary Art MA at the Royal College of Art. We saw videos from the Venice Biennale, filmed by Lia herself during a time when nobody had the money and resources to get there… We had live TV segments in the studio. A memorable one was with the students who rose up against the stiffness of the art school (does the Cutter group still ring a bell for anyone?). We frequently hosted artists from outside the capital city, from Iași, Târgu Mureș, or Cluj, who had nowhere to wait for their train… Vienna Days in Bucharest had our studio (more precisely the Center for Art Analysis) as a host (alongside the great state museums ha ha ha). In the end, it’s simple: we had a space in the city center while others didn’t and while public lectures and debates were rare or totally absent.

We had barely reached Picasso in our art education, so when we started traveling, the art of the 1960s-1990s hit us all of a sudden. That magnitude of information, the history we had been cut off for so long, was a huge motivation. We wanted the same for back home. And for people to understand, we needed to show them models. Our activity as an experimental space was financed (in terms of information and money) by our activity as artists. Our careers fed the discussion.

We didn’t only want to know world art, but also to disseminate it and, especially, to discuss it. Hence the studio as a space of knowledge production, analysis, interaction, and less as a space for painting or still lifes… In the meantime, the AAC – Arhiva de artă contemporană / Contemporary Art Archive (about which you can read in the issue of ARTA about archives) became the CAA – the Center for Art Analysis. And, just to be clear, both are Lia Perjovschi’s ideas and practice. I just promoted them.

The archive’s publications which recovered practices and concepts that were nonexistent in Romania (installation, photo-video, performance art) became publications for analysis and criticism. “Defective Draft” is the first critical take on the National Museum located in the Parliament building (by a corrupt government and a president under criminal investigation). For years, Lia carried backpacks full of information from the west, organized them into files, and offered them for consultation… We had become kind of like meeting agents, putting curator x in touch with artist y etc.

In 2000 we were the moderators of a live TV show on channel 1 on TVR (Romanian Television), Saturdays from 11 to 1 pm. Three hours live talking about culture. All our studio experience and all the CAA’s experience were broadcast nationally. Chris Burden in every Romanian’s home. Ha ha ha…

Everything out in the open – that was always our concept regarding being, making, and disseminating art.

The idea came after we had organized one of the only open studios of the 1990s. And we made it like an artwork for the exhibition and catalog “Experiment…” which attempted to condense between its covers everything that seemed different and brave from the art of the 1950s-1990s.

For us, dialogue, education, and sharing were art.

And, of course, after 20 years the Arts University kicked us out. Without remorse and without understanding a single thing. (Geta Brătescu had it for 10 years, we for 20, so what?)

Tell me where a young artist can go nowadays and discuss their practice honestly, one on one, without arrogance and pretentiousness?

So yes, we were the pioneers of an activity that was never formalized, which we fed with our energy, knowledge, money, and time, and which nourished and strengthened us in turn as artists and citizens.

M.I.: You have experience with independent spaces from many cultural areas, so could you talk about what is characteristic for the Romanian scene, if anything? At the same time, you have a declared interest in collaborating with alternative spaces, artist-run initiatives, the public space, and publications. What is, right now, the artist-run space model that works best?

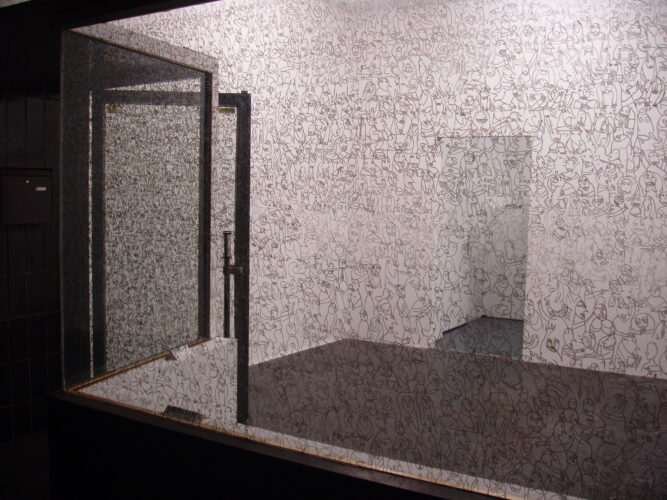

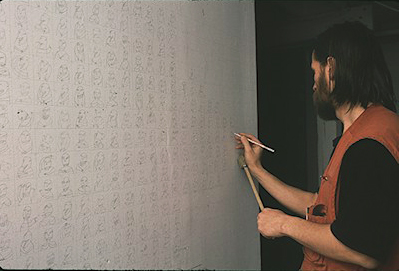

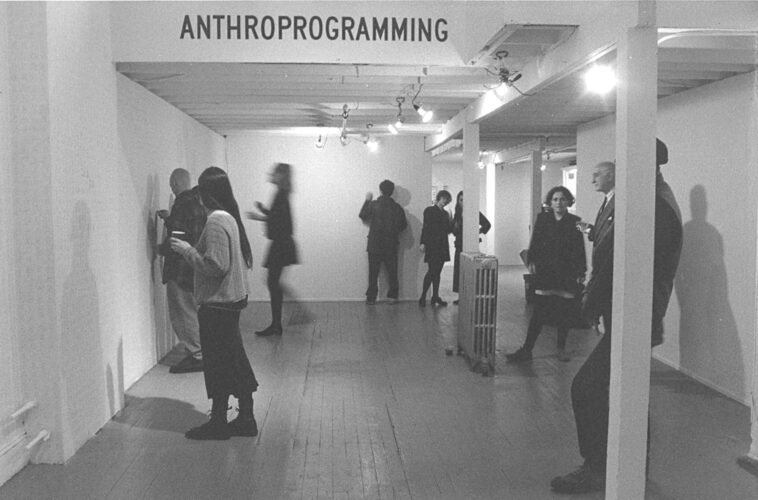

D.P.: Some of the most important moments in my career are connected to artist-run or project spaces. Atelier 35 in Oradea, at the end of the 1980s, was my real art university. I learned art by making art shows. At Franklin Furnace New York in 1995 I made one of my most radical projects (having drawn all over the exhibition space, from floor to ceiling, in pencil, I offered erasers at the opening and the audience erased me, literally). Collective Gallery Edinburgh was one of my first projects in the public space. At Electroputere Craiova and Centrale Kosovo I partnered up with Lia, she had her Museum Knowledge inside, I had the walls outside… At Casa Tranzit Cluj, instead of an exhibition, I made a public debate together with Lia, for which we brought together three generations of remarkable townspeople, the elder Doina Cornea and Eva Ghimesi, the mature Tim Nădășan and Antik Sandor, and the (then) young people from Philosophy and Stuff.

Last year, I was exhibiting with transit.ro Bucharest at Sala Floreasca and in the exhibition “I also donate for UNArte” at Cazul 101 gallery, and this year I am exhibiting at White Cuib in Cluj and Indecis & Secret Garden in Timișoara.

I’ll take part in any independent, alternative project, outside the closed-mindedness of the state or the market. When I say “take part,” I most often mean that I finance my own presence. I can, so I do it. I grew up with artist-run spaces, it’s my turn to support them. I participate with all my artistic strength and my international know-how (I’m not after a fee, sometimes I’ll even make things that can be sold for the benefit of the space). Besides, I bring in people. I’m aware that my name means something, and I offer it in full solidarity.

The more I exhibited outside Romania, the more I exhibited in Romania.

What is typical for Romania is that there are a lot of pioneering projects. The first open studio. The first critical platform, the first decent exhibition space, the first debate space, the first white cube, or cuib ha ha ha, etc. I’m invested in the struggle with obtuse local administrations (in Romania or in Milan), with the visually illiterate political elite (in Romania), with mainstream institutional arrogance (in Romania or in New York), with the lack of funds (in Romania), or with the defeatism that needs to be overcome every day (in Romania again).

And now, a feature that has been baffling me for 30 years. Even though we’re poor and on the brink of bankruptcy, the independent world wants to look like in a Taschen catalog. We never developed an arte povera (or an architecture of poverty), the art of cheap material, art without hardware. We are not conceptual, immaterial. We paint and sculpt, we want HD projections and iMacs.

Because we lack and don’t know how to obtain spaces, we’ve developed murals, which are more and more baroque, more and more colorful, surrealisms and metaphors galore… The public space is no longer a place for ideological and social critique, it is a wall of paintings. But it’s fine like this, perhaps after all the melodrama we’ll finally write some manifestos.

There’s been a more radical wind in recent years, with things said more frankly, more critically… thanks to the LGBTQ+ community, feminism, the local-international mix (Romanian artists studying in Düsseldorf or staying in London for a while and then coming back with new ideas, international couples, etc.).

Still, I’m amazed that artists who lack this and that never stage public protests, never graffiti the Ministry of Culture or the Pangrati studios. If we didn’t have Kunsthalle and museums, we made our own (I’ve been drawing in Revista 22 since 1990, and Lea has been founding institutions, like the Contemporary Art Archive, the Center for Art Analysis, and the Museum of Knowledge). We’ve done all we could with what we had (we used our studio, Romanian Television, the museum’s guard booth, school blackboards, pages in newspapers, international alliances, chalk, markers, and pens).

As a sign of protest (dubious founding, dubious location, dubious management, etc.) I never stepped into the National Museum of Contemporary Art, and I am boycotting the Romanian Cultural Institute, the Ministry of Culture, and most state institutions in Romania (after they lapsed one by one into nationalism and pathetic discourse) as well as the arrogant and commercial Artmark, which pretends to “educate,” by mixing in sculptures ridiculously attributed to Brâncuși with Meleșcanu’s pen. We don’t apply anywhere and we ask no one for permission to exist as artists.

Why? Because we’re independent.

What does a young artist with nothing, who has reached GAEP, Sandwich gallery, or Salonul de proiecte, do? Why are they quiet?

You ask me about which model I think would work best.

Probably a hybrid one, with an anchoring point (A35 and CAV in UAP-owned spaces, White Cuib with architects and IT people in Cluj, B5 in Iotzo Bartha’s studio, 030202 at the Comedy theater), new territories (Sandwich at Liste Basel, 101 at Berlin Art Week), or that revitalize forgotten places (the thermal power plant in Slănic Moldova, an open-air cinema in Eforie Colorat, a culture house at Cecalaca). The functional model is the one in which the founder is collective and invests not only money and energy, but also themselves (Indecis, Secret Garden, Etaj).

There might be more, but those are the ones I’ve collaborated with…

M.I.: The pressure and difficulties of such projects are primarily a matter of autosuggestion, and whether an independent initiative works or not depends on various forms of state financing or the dynamics and demands of the art market. To what extent do older idiosyncrasies make way for new ones, and which model of initiative manages to get close to the public in its totality, especially in a context where the notion of public is opposed to the private?

D.P.: In Romania everyone depends on the Administration of the National Cultural Fund (AFCN). Romania has not generated alternatives (other foundations, funds, sponsors, and partners), except vaguely and rarely. The real kicker is that both independents and state institutions depend on the AFCN. It’s preposterous.

Romania is in the early stages of the “art market,” so if independent initiatives don’t have a law firm, an auction house, or a collector, God help them… You can’t support yourself by selling books, for instance, as small Kunstvereine in Germany and Austria do. And there aren’t really funds for contemporary art on the city or county level.

They do for festivals dedicated to beer, the Călușari, the Middle Ages, van Buuren, or strawberries. For the kind of street art that “improves the city’s appearance” you have funds. If you add a still life painting workshop for kids, bam, you got yourself some public cash. Lately, everyone’s a doctor in art and everyone teaches kids how to paint. On easels.

But there’s no money for art research and production. What state or private entity in this country will give you a 2-3-year scholarship to write a book of contemporary art criticism, if I may ask?

As I’ve said before. The hybridization and relativization of how we define the public is in full swing. The notion of public as opposed to the private? I do public projects when working with private galleries. For me, the National Museum, the Arts University, and the Pangrati studios are a family business. A private one.

Right now, some private initiatives in Romania (Art Encounters, Plan B, Ivan, to name a few), do more for the art scene than national museums… Same with the artist-run spaces Salonul de proiecte, Sandwich, B5, Camera K-arte, Cazul 101, and the other ones mentioned above.

The public’s eyes are on Tik Tok and NFTs.

Let’s be real, for us the pandemic was the big fix, 30% of visitors is precisely our audience. Why should an audience be demanded of me if I can’t finance myself decently? That’s why I drew in the public space in Sibiu. I count every passer-by and everyone waiting for the bus as my audience ha ha ha.

And now the bright side. I’ve seen Eforie Colorat, Centrala In Context in Slănic, and Indecis full of visitors… there’s a lot of interest in what White Cuib or Salonul de proiecte exhibit. In Lia’s reading room installation on the top floor of Astra Library in Sibiu all the desks are occupied by young people.

There’s a lot of pressure on autosuggestion, but it’s a good lesson. That’s what I would teach in schools. How to be a legal freelancer. How to found and manage an artist-run space. How to get money to finance your project. What sources there are. Who your allies are. What possibilities there are.

M.I.: The last two years have been very hard. Especially now with the emergency someplace I won’t name right now (and when we all hope the situation will be defused), I don’t want to repeat the clichés about the pandemic’s impact – we have all felt it. Of course, we can’t generalize: new spaces have been opened and new openings that we didn’t expect have been made, and it is in the struggle of the traditional functioning model that the importance of the individual, transitory, and the openness to change direction has been redefined. I would therefore like to situate my question not in a suspended present, but in an uncertain future – what would a possible evolution of artist-run initiative look like, what would be a likely scenario and an ideal one?

D.P.: I will be critical. I haven’t seen anything new. A different form, practice, or aim. Maybe a more radical decision. Revista ARTA for example came out in color, even though the situation was gray. Now was the time. Nobody was asking for an audience. You could do anything. In a museum, or on the sidewalk in front of the museum. Or on the utility poles and the billboards in front of the University of Economic Studies… on the sky or in a rearview mirror.

The scene wants to do the same things in the same places. You can’t anymore!

I haven’t seen any solidarity, be it between independents or those dependent on public funds and the rest of the world. The art scene has become fragmented. Everyone for themselves.

Vaccination rooms still have empty walls.

Now is when we need a federation of independent spaces. The independent sector has to demand its rights, to stop applying alongside the National Theater to the same AFCN. New spaces must be found. On TV, on Instagram. How come there are film festivals without a visual arts section? How come there are communal or neighborhood libraries with no visual projects? How come not every competent city has its own city art gallery, its public Kunsthalle?

This is the time for collectives, for pooling resources together. Perhaps new alliances with the UAP and local high schools can be made? With museums with butterfly collections? Perhaps we can find partners instead of sponsors? Perhaps our “unions” should have some members that aren’t artists.

We need to be more inventive. In the end, a sheet of paper is an independent space…

I think that every artist, every collective, and every project needs to redefine itself and restate its goal. Why and for what? Do we want to be revolutionary? Do we want to be local heroes? Do we want to change the arts? The world? Do we want to have a decent life, a quiet place where we can shine once every two weeks? Are we still curious? Do we still have a drive? Do we still have it in us?

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Mălina Ionescu

Mălina Ionescu (b.1978) is a visual artist and theoretician, holds a PhD in Museum Studies, currently curator at MNAC Bucharest – The National Museum of Contemporary Art Romania. Lives and works i...

Comments are closed here.