May 2007: Berlin – Potsdamer Platz, Germany

I distinctly recall how I wanted to begin my introduction with the sentence: “In Berlin, the hot summer has come in the month of May.”[1] I’m not sure why this sentence suggested itself with utmost importance; maybe I only aimed for some sort of rhetorical effect. But it was true that when I met Pavel for the first time in Berlin, it was May and it was very hot. We cooled down with a drink and we talked about (Eastern) Europe, borders and the experience of the contemporary baroque, as themed in Shoes for Europe (2001), Welcome to EU (2006) and Baron’s Hill (2006). The latter I had just recently seen at Neue Nationalgallerie. I wished I saw Shoes for Europe in Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta 11, but at 19 I had no interest in, or knowledge of, contemporary art. I also remember how, following the discussion with Pavel, I quickly resolved to book a trip to Documenta 12, to faithfully return ever since.

Reading this interview again now, I’m happy to see it has aged well. What Pavel said about migration, borders, work (artistic or otherwise), and the art world still rings true. But I pick up a detail from that discussion that I have completely forgotten: right at the beginning Pavel told me how, around 1999 when he was living in between the Netherlands and Belgium, he had started to collect laboratory data about the annual increase in water levels, which indicated that the planet is getting warmer.

Was I thinking about Global Warming in 2007? No, not really; yet I did insist on beginning my introduction by saying that in Berlin the hot summer had arrived earlier, in May.

November 2007: Paris – Centre Culturel Suisse, France

Do you remember the ‘Neue Europa’[2]? Do you recollect the time when cultural hybridity was in (intellectual) fashion? And – precisely this is the question – who had the privilege to move around that post-socialist and post-imperial Mittel Europa and experience it as ‘New Europe’? If anything, it was a handful of artists and curators who were already doing the work of deconstructing ‘Europe’. Pavel was doing his bit: see the haunting images of train wheels and railway gauges at the border between Romania and Moldova (Shoes for Europe, 2001); or images documenting the journey of a raffia bag from Chișinău to Western Europe (Eurolines Catering or Homesick Cuisine, 2006).

On that wet night in November the raffia bag travelled from Chișinău to Paris[3]. The sarmale, wine and plăcinte that Pavel’s parents lovingly made tasted like home. In Artforum Anthony Gardner wrote how the work entwined ‘images […] to suggest a fragile dialectic of nomadism and localism.’[4]

Pavel Brăila, Shoes for Europe, video, 2002

September 2010: Chișinău -Valea Morilor, Republic of Moldova

On the previous evening Pavel performed again his Welcome to EU (2006), stamping Moldovan passports with the 12 golden stars of the European flag. The space was buzzing, and I thought there was cultural vibrance there of a kind I had not experienced in Bucharest. It was the first time I saw the performance live. On the following afternoon we agreed that I will write a text to go in the Romanian Cultural Resolution catalogue[5] and Pavel showed me a first draft of his Chișinău – City Difficult to Pronounce (2011). It vaguely reminded me why I had liked Baron’s Hill – something to do with how the camera insists on details – but I understood that this work is about place, memory, and loss. As I watched it, I couldn’t help thinking that once this city becomes easier to pronounce, something of the extraordinary energy and lust for life I experienced during those days will be irremediably lost.

February 2011 – Loughborough University, United Kingdom

‘Spin’, ‘flight,’ ‘accelerate’ – ah, this comes at the end of a year of reading Deleuze and Guattari[6]! I’m far removed from that place now: I go over some sentences that remain stubbornly opaque. And yet, can one disagree that ‘in his images, everything performs’? I can’t forget Pavel’s body crawling and twisting on chalk-drawn black floors in Recalling Events (2001). Would this be something that Deleuze and Guattari have recognised as an ‘asygnifying semiotic’? I still think that describing Pavel as ‘an engineer of political poetry’ is very accurate. In 2007 Pavel did tell me how documenta 11 cured his imposter syndrome (he does not have a degree in Fine Art); but even if it didn’t, I now know that, if anything, the world needs more engineering and more poetry.

June 2014 – St Petersburg, The Hermitage Museum, Russia

In the Summer of 2012, there was a UEFA Euro Tournament in Poland and Ukraine, and matches were played in Lviv, Kyiv, Kharkiv and Donetsk. In the Winter of 2014, there were Olympic Winter Games in Sochi, Russia: for years, up to 710,000 cubic metres of snow were stockpiled high up in the mountains to prevent the area’s subtropical climate from derailing a global event. In March 2014 I watched live streams from Kyiv’s Maidan Square, and footage of coffin processions and public funeral ceremonies. Between June and October, 2014, Manifesta 10 occupied the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

I watched a recording of Pavel’s public performance, Golden Snow of Sochi Olympics on Youtube[7]: 300 kg of snow collected from Sochi were unloaded from black Mercedes cars into the Palace Square. As the snow melted away and children started a snowball fight, Pavel observed: “Now you see, we don’t want war, we want fun”[8] (to be continued in Athens).

Pavel Brăila, Cold Painting, performance, Manifesta 10, Palace Square, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, 2014

April 2017: Athens – EMST, Greece

September 2017: Kassel – City Centre, Germany

A splinter sun on my chest[9] and sweating at 28 °C, I was attending a meeting in Athens where post-war Europe met New Europe. I think this meeting occurred about 10-15 years too late. I must confess that I found beauty in documenta’s tragic downfall: there had already been rumours that the German bureaucratic machine was poised to have a nervous breakdown in Athens. We were going to see Pavel’s jars of Sochi snow in the EMST: 98 jars to correspond to the 98 Olympic medals, all labelled with a graphics to remind us that at the Sochi opening ceremony one snowflake (the red one) had failed to metamorphosize into an Olympic circle. ‘When you look carefully at this snowflake, the red one, it’s like a bloody bullet wound on Ukraine,’ Pavel said. I wondered if the snow had already melted at the Greek border: perhaps sending it via a raffia bag would make its journey easier?

Months later I noticed, for the first time, that German infrastructure is not what it used to be: my train for Kassel was very late. But I eventually got there. Pavel met me and I was very happy to embark on his Ship of Fools (2017), the public bus line 16, half submerged in sea water. In the documenta daybook I wrote about ‘a changing world mediated by water from the Aegean sea.’[10] I am now obsessed with an apocalyptic image: a bus half submerged in seawater from the Aegean sea, running for safety (but where?) in the burning landscape of the Greek summer. In 2023 the National Observatory of Athens concluded that between 2017 and 2023 more than 55,000 hectares of land were scorched – 23% of the Attica region.

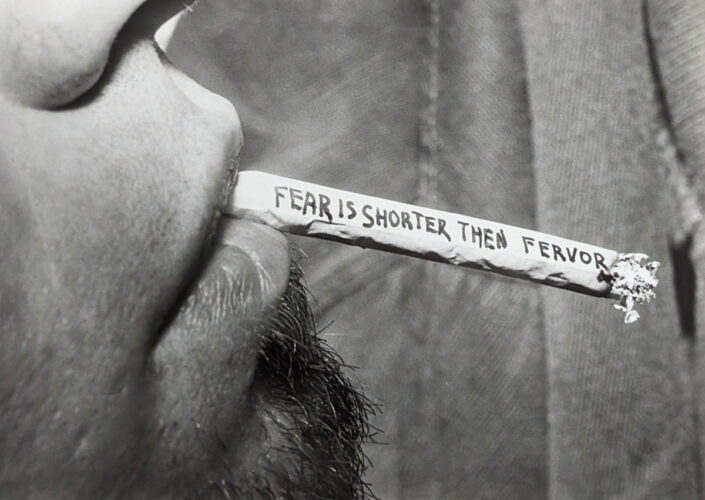

September 2020: London – Home, United Kingdom

There isn’t much to do in a pandemic. On TV and YouTube X Factor and Got Talent ran in a loop, yet I thought one should forget Simon Cowell, because DJ Benzo was the real thing[11]! In the year 2100 a Benjaminian cultural historian will unearth BenzoKaraoke from the depths of the internet and will argue how it represents a symptom of cultural metamorphosis: ‘It became mandatory,’ they will have said. ‘From then on, all American road movies started with a BenzoKaraoke!’ And they continued: ‘But BenzoKaraoke’s cultural significance can be grasped only as a dialectical image, in juxtaposition with something like Neue Deutsche Härte and Rammstein’s piece Benzin, released almost a century ago. One needs to take DJ Benzo’s Insta-Talent data feed out of its historical continuity and confront it with these lyrics as performative speech act:

Willst du dich von etwas trennen,

Dann musst du es verbrennen.

Willst du es nie wieder sehen,

Lass es schwimmen in Benzin.’[12]

February 2024: London – Home, United Kingdom

The Monthly Climate Bulletin of Copernicus – the European Union’s Earth Observation Programme – reports that February 2024 was the warmest February since 1940, when data was first recorded. February was also the 9th consecutive warmest month. ‘The average global surface air temperature for February was 13.54°C, 0.81°C above the 1991-2020 average for February and 0.12°C warmer than February 2016, the previous warmest. Sea surface temperatures over the extra-polar regions reached a new record absolute value at 21.09°C.’[13] In London, Berlin, Athens, Bucharest, Chișinău, Kyiv, St. Petersburg, as well as everywhere else, the hot summer is determined to come much, much earlier.

[1] Vlad Morariu and Pavel Brăila, ‘On the Western Track.’ In: Idea, no. 27, 2007, pp. 96-104.

[2] See, for example, The New Europe. Culture of Mixing and Politics of Representation. Curated by Marius Babias and Dan Perjovschi. Generalli Foundation: 20/1/2005- 24/4/2005. Available here.

[3] See Europe en devenir. Partie II. Curated by Marius Babias. Centre Culturel Suisse, Paris: 11/11/2007 – 30/12/2007. Available here.

[4] Anthony Gardner, “L’Europe en Devenir (Partie 2)” (Europe of the Future [Part 2])’. In: ArtForum: Critics’ Pics, 2007 (online). Available here.

[5] Vlad Morariu (2011). ‘Pavel Brăila: Material Poetry.’ In Bojenoiu, A & A. Niculescu (eds.), Romanian Cultural Resolution, Hatje Kantz Verlag, pp. 113-121, ISBN 978-3-7757-2848-5

[6] Ibid.

[7] Manifesta 10, Public Programme. Pavel Brăila. Golden Snow of Sochi. Available here.

[8] Sally McGrane, ‘Allowed a Space in Russia for Criticism, Artists Have Fun With It.’ In: The New York Times, 9 October 2014. Available here.

[9] Pavel Brăila, Splinters of the Sun, first produced in a limited series for the Moldovan Pavilion in Milan, at World Expo 2015.

[10] Vlad Morariu, ‘Pavel Brăila.’ In documenta 14 Daybook, edited by Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk. Also available here.

[11] See All 10 episodes of Brăila’s BenzoKaraoke here.

[12] ‘If you want to part with something/ then you have to incinerate it./ If you never want to see it again/ let it swim in gasoline’. Rammstein, ‘Benzin,’ Track no. 1 of Rosenrot. Released 28 October 2005 by Universal Records.

[13] Copernicus, ‘Monthly Climate Bulletin’ published on 8th of March 2024. Available here.

POSTED BY

Vlad Morariu

Vlad Morariu is a researcher, curator and academic based at Middlesex University London. His work sits across 20th Century philosophy, semiotics, and visual and material cultures, particularly focusin...

Comments are closed here.