Comprising a series of object-photographs, collages, and textile installations, the project from someone other than myself, exhibited by Aurora Király at Anca Poterașu Gallery (financed through the SEE Grants 2014-2021, as part of the RO-CULTURA program) is a complex artistic project that is hard to fit into one category. Her mature research is rather an investigation into the dissolution of categories, genres, and borders, engaging in a relevant inter- and trans-media discourse that relates the fluidity of identity to the qualitative flow of time – duration as a chance encounter of the past with the present and future.

from somewhere other than myself is impossible to place in a linear narrative, difficult to fix in time, space, or one single medium. The exhibition adopts the architecture of a rhizome, a network where all images communicate with one another. A hyper-narrative structure is produced, a multiplicity of wires that tie the characters of the photograms to those in the collages or textile installations, inviting the viewer to slide along the chain of free associations and memory-images, down the Bergsonian flow of spontaneous memory. One moment we are in the artist’s apartment, next to her beloved Pisi (as a collage character dressed in animal print), a few seconds later we are in Belgium, in the shade of trees transposed onto glass through silver emulsion. Thanks to another object-photograph, enclosed in glass and Plexiglas, we return to the center of Bucharest, next to the high-rise in Piața Palatului, and then back to the collages and installations where the artist, in the light of an elegant pink lamp, reads about contemporary dance and avant-garde experiments, identifying in turn with famous performers and choreographers like Léonide Massine, Yvonne Rainer, or Mette Ingvartsen.

One can say that the project comes into being in a transitional space, at the intersection of the posthumanist discourse around the self and nature and the discourse marking the medial shifts of postphotography and postcinema. The important question that Aurora Király raises is whether in this post regime, marked by a lack of faith in beauty or essence, these two unstable territories might not in fact conceal an unexpected poetics and an essence beyond essence.

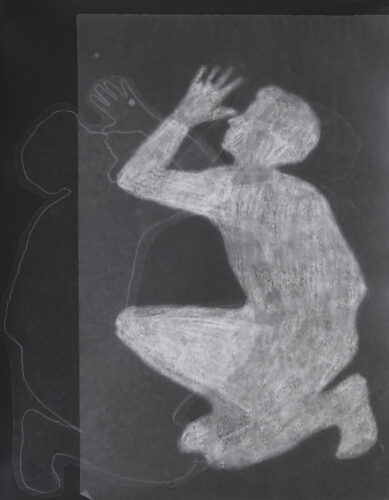

We see that photography, which Benjamin sees as lacking aura and the pleasure of contemplation, becomes for Aurora Király, in her elaborate photograms and glass prints, the revelation of an unfixed but precious and unique object. When it is projected onto the lightbox, it reveals a convoluted process while at the same time initiating a subsidiary game with materiality, simulating the touch of a light, see-through fabric and the rustling of tracing paper. We find ourselves exposed to a paradoxical type of poetry that blends craft with dreams and enthusiasm, bringing ancient Greek horizons back into presence. Old internal mechanisms of art are resurrected – the Apollonian and Dionysian, beauty and light, dream and the revelry we need to accept the tragic truths about human existence.

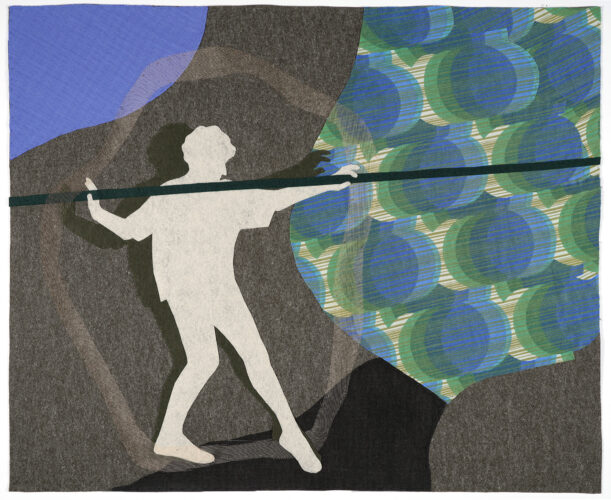

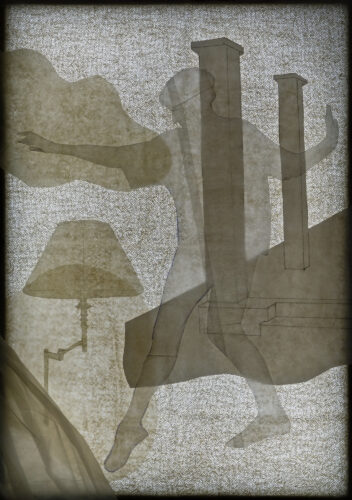

What contributes to this are the symbol of the column, abstracted but always present somewhere in the background, as well as the characters, often seen in profile, in movements that seem to deconstruct mythologies portrayed on vases and amphoras. This series of outline-figures, featureless yet expressive, whose profiles reproduce the artist’s, revives the ancient discourse of persopon and persona: individuality as an accident, identity as a mask. Thanks to the artist’s remarkable position as Pierrot, the singularity/multiplicity game also gains connotations from the Commedia dell Arte, improvisations woven around human typologies. Additional references are provided by Léonide Massine’s posture in the ballet piece Pulcinella, a collaboration with Picasso and Stravinsky that revives the program of the avant-gardes. We may conclude that the characters make up just as many heteronyms of Aurora Király which function like an hourglass gathering time, turning it into gesture, giving the moment not just extension but a body of gauze, cotton, or felt. In this formula of successive references and identifications, the self of the mature artist reveals itself as fluid, multiplicitous, and self-fashioned, while still being anchored in the biological body. Restating the message of the good life developed by theorist of aesthetics Cristian Iftode, the artist invites one to self-recovery as ethical-aesthetic subjectivity, practicing the art of living in the horizon of freedom, multiplicity, and opposition to biopolitical normalization.

All in all, we see how these ethical or aesthetic recoveries do not damage the relevance of the project, which remains above all a contemporary analysis of the technical image and the way in which it shapes identity and our relationship to the natural or urban landscape. Who am I if not the sum of all my posted selfies and pictures? Who am I if not all the places and landscapes I inhabit? The series Viewfinder Clash, containing poetic landscape photographs transposed on glass treated with silver emulsion, continues the analysis of the photographic act itself previously developed in projects like Viewfinder and Viewfinder Mock-Ups (2015-2019). In its similarity with the act of consciousness, photography presupposes here the subjective selection of one perception from an infinite field of possibilities. In the Bergsonian view of the world as a system of connected images, photography moves away from merely generating representations, and the perception impregnated by memory-images differentiates itself from the machinic photographing of things. Moreover, by replacing concepts with uses of focal length, filters, colors, and framings, photography becomes thought, a discourse capable of delivering a more substantial answer than the quantitative, scientific one around the meaning of “affect as affect,” around the multiplicity and instability of the self, around the intimate structure of space or time.

I salute the connections drawn by Bogdan Ghiu with Bergson’s writings as well as with Deleuze’s ideas in Cinema II around cinema-thinking and the time-image practiced in postwar auteur film. Standing alongside such filmic masterpieces as Je t’aime, Je t’aime or L’Année dernière à Marienbad, directed by Alain Resnais, Aurora Király’s project adopts the same fascinating discourse of crystals of time, the same cyclical narrative pointing to the non-chronological, mathematically non-quantifiable structure of duration. In this sense, the lesson we learn from the characters portrayed in dance poses in 50s or Soft Dispair and Soft drawings_Subconscious Narratives is the same lesson which states that behind any useless quantification into days and hours, “time as time” is closer to a flow, a continuity. Just as a dance only truly begins once the steps have been forgotten and the movements evolve freely from one another, time as flow can be understood and felt only with the abandonment of any attempt to sequentialize or spatialize it (on the screen of a clock, on the pages of a planner or a calendar).

As far as the recovery of the self is concerned, it would concern inhabiting a space with the other and the intimate horizon of familiar things. In the collages Subconscious Narratives, the artist creates a textile Umwelt in which everyday items – a lamp, a coat hanger, an umbrella – are cut from the fabric of a worn dress or an old couch, surpassing mere functionality, redefining themselves as phantasms that populate dreams or as authentic things that, thanks to their ability to “convey trust” and existential meaning, make possible the assertion of the self as Heideggerian being-in-the-world.

The connotations of the title Subconscious Narratives rejuvenate the play between memory and perception, the mechanism by which a memory returns from virtual to real, from subconscious to conscious. There is no doubt that this project, whose internal architecture is that of a permanently rearranging archive, represents an investigation into the subjective mechanisms of memory, as Cristina Stoenescu, the exhibition’s curator, remarks. The basis of this investigation – the measure of manual labor and an essential ingredient of photography – is qualitative time, with its spontaneous loops and leaps between present and various layers of the past. What remains is for us to let ourselves be carried away by this flow of duration in order to learn to differentiate matter from memory, the real from the virtual, the present and the moving body from the past and memory as an infinite reservoir governed by the secret laws of the subconscious.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Raluca Oancea

Raluca Oancea (Nestor), member of International Association of Art Critics (AICA) and European Network for Cinema and Media Studies (NECS), is a lecturer at The National University of Arts in Buchares...

www.Dplatform.ro

Comments are closed here.