Within the Landschaft (Peisaj) project undertaken by Galeria Posibilă and Fotogalerie Wien, exhibiting ten Romanian artists in Vienna and six Austrians in Bucharest is just the tip of the iceberg. Going beyond the works on display, what this collaborative process highlights is a number of essential transformations of contemporary visual art as it re-adapts to an age of post-photography, post-cinema, and post-truth. For starters, the collaboration produces a free space of meditation (Gleizal) in which the artist can deliver an independent, critical discourse capable of remolding the social. Space-producing art un-conceals a world (Heidegger): in the light of a new kind of Aufklärung (an illumination from the age of the Enlightenment and any cult of positivism), actors, relations, and an entire mechanism in which contemporaneity becomes part of the artistic act are unconcealed.

Landschaft (Peisaj) reveals a paradigm in which the artist becomes anthropologist, historian, and social critic (see Lucian Bran’s in situ investigations on a local landscape that was “borrowed” to shoot an American TV series, or those by Valentin Cernat and Mihai Șovăială on the Danube-Black Sea Canal, or the way Michele Bressan and Bogdan Gîrbovan map out the past using a metal detector). At the same time, the curator and gallery owner redefine themselves as mediating artists, as essential catalyzers of the art scene. Art as game and competition is performed by curators Susanne Gamauf and Alexandra Manole, by gallery owner Matei Câlția – passionate about the topic of nature and habitation – by the Fotogalerie Wien collective, together with the participating artists. All are engaged in a game of territorial generation. The resulting territories are placed outside any national perimeter, as free territories of poetry, noting that this poetry is not organically embedded in the social fabric (Bogdan Bordeianu, Irina Botea, and Nicu Ilfoveanu develop a visual phenomenology in which time and the present are investigated in relation to housing and peripheral poetry).

The Baudelairian game reveals the image of the artist as flâneur, a crowd person and world citizen. In this sense all the exhibited artists are moving figures, travelling throughout the art-life continuum guided by the rules of flâneurism and deterritorialization. Among the Romanian artists exhibited in Vienna, Irina Botea, a true world citizen (whose path through life encompasses London, having done a PhD at Goldsmiths, Bucharest, and Chicago, in which latter two she taught at various art universities), wanders through Transylvanian landscapes whose picturesque quality clashes with the decay of villages, mines, and abandoned factories. Michael Höpfner traces lines of flight with his foot in the Tibetan Plateau and with threads of wool throughout Galeria Posibilă (reminiscent of how Tibetans spin wool during long walks through nature). In fact, most of the Viennese artists exhibited in Bucharest showcase projects from residencies far away: Yosemite National Park, a remote forest in Finland, the Hudson Valley, a pine forest in the Nevada desert, and, last but not least, the Tibetan Plateau, nicknamed “the Roof of the World.”

I believe that Landschaft (Peisaj) is a complex attempt at redefining photography and film in the digital age (beyond narrative and the traditional mirroring of the real), even aiming at redefining the concepts of landscape and contemplation. This is done against the contemporary backdrop of art’s complicity with the posthumanist doctrine of reconsidering nature and “letting it be,” as well as of art’s interdisciplinarity (moving art closer to knowledge and the sciences to aesthetics). Moreover, the landscape, which Walter Benjamin demotes to an element of disinterested contemplation, is redefined by contemporary photography as a component of the anthropology of social life. In other words, it becomes a complex mediator between art, geography, biology, and anthropology. Or, in the words of architecture theorist Christian Norberg-Schulz, the landscape (be it natural or urban) becomes an element of identity. Being becomes synonymous with inhabiting, in equilibrium with the heavens and earth, says Heidegger, and Schulz, in Genius Loci, states the following: we are what we are in accordance with our buildings and landscapes.

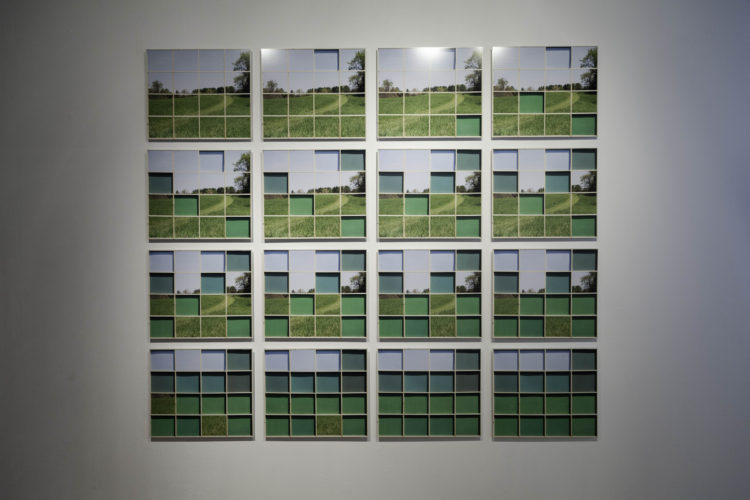

These new approaches to the concept of landscape are taken up by the six impressive Austrian projects exhibited in April 2019 at Galeria Posibilă. Markus Guschelbauer’s Taming of Landscape proposes a different contemplation of nature, through the rectangular grid of culture. A natural view in the Hudson Valley, half sky half pasture, is photographed a number of times through a wooden frame divided into a 4×4 cell grid. This orthogonal object, built by the artist during his U.S. residency as response to the obsessive partition of U.S. territory (at the level of state, yards, and politics, physically and administratively) can be read as a sculpture, but also as an instrument of sight. Initially all squares open onto the landscape like the Renaissance pictorial standard. The cells are then covered one by one with an image of the average color of the pixels in the cell. The transition from reality representation to the total fragmentation and abstraction of the landscape – keeping in mind the structure’s resemblance to a jigsaw puzzle or the architecture of a beehive – opens up a debate about the relationship between nature-culture, analog-digital, and play-contemplation-work. The artist also highlights the opposition between the orthogonal nature of the mental territory of reason and functionality, and the organic nature of work.

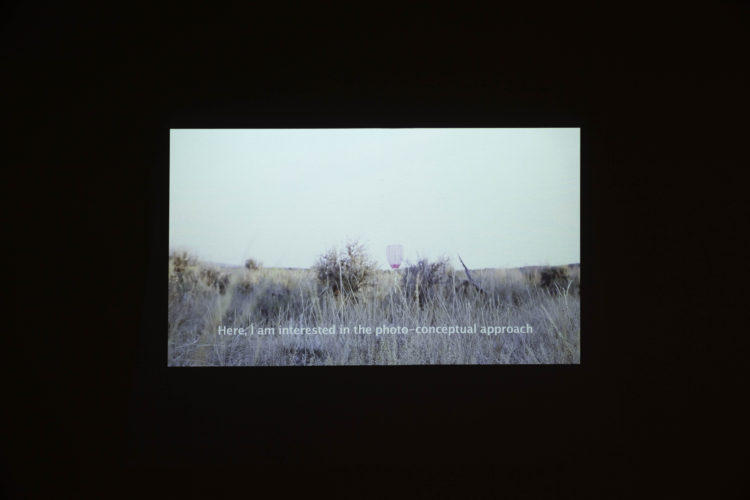

In her video installation Sculpture Park Montello, produced during a residency in the Nevada desert, Lea Titz creates an interesting kind of landscape: a cultural, hybrid, and fictional landscape. Using found materials and apparently banal everyday objects, she constructs a series of sculptures that she then places in a nearby pine forest (making sure to include Guschelbauer’s orthogonal object). The work drives home its point through the immersive way the landscape is filmed (with the camera close to ground level), which leads to a game of proportions, an almost ritualistic motion, a feeling of disorientation and strangeness. This exercise in artistic phenomenology, mediated by technology in the fashion of the Italian neo-realists, admits the viewer into a poetics of the banal which changes their understanding of duration and distance. The proximity to the earth offers a novel perspective, in which shrubs become giant trees, while culture is surrounded by nature.

In his travel projects in the wild, Michael Höpfner offers a similar exercise in order to show that journeys by foot in nature can’t be measured in meters, but in lived experience. In a 2017 interview about this style that he has been practicing for more than 10 years (in the Himalayas, Tibet, Szechuan, Tajikistan, western China) the artist claims to be attempting to re-learn the act of looking from nomadic peoples. Their relation to space and time (measured for instance by a woolen threat spun during a walk) demonstrates that this counter-society can offer the West a counter-perspective of nature that is unaltered by positivism.

During his Tibetan travels that form the basis of the project exhibited in Bucharest, Höpfner, unlike other well-known flâneurs, like Richard Long, does not intervene directly upon nature, instead generating notes and visual discourse (black-and-white photos that reveal deep nature’s resistance to change). The notes (whose visual aspect sometimes mimics the rhythms of nature found in the photos) show the artist’s affinity towards literature (from which he often quotes) and his valuing language. The installation of wool thread and stones, whose shape (resembling a constellation, a map, or, why not, a border) can be modified by the visitors’ footsteps, and seems to suggest that the “border” is first and foremost a mental construct. On the opposite end of landscape commodification under the influence of exotic tourism, the project Însemnări despre o excursie la Drak Yul [Notes on a Trip to Drak Yul] reveals Tibet as nature in and for itself, a source of the sublime, a source of springs, and a place where people live close to the heavens.

Thomas Albdorf, Claudia Rohrauer, and Robert Bodnar probe the condition of the environment in parallel with that of the medium of photography. While natural phenomena are abstracted into forecasts, photography becomes an object or canvas, and photographed sculptures are disseminated digitally. In this sense, Albdorf’s project At the River Bed showcases a series of photos of ephemeral installations built in nature only to be photographed and shared online. The backdrop is Yosemite National Park, one of the most photographed places in the world, and what comes into question is the function of the flâneur in the digital age. We know from Benjamin that the aura of a being, landscape, or artwork (that concrete, direct presence, that feeling of “here and now”) becomes lost in the age of mechanical reproduction, with the advent of photography and film. We know from Groys that the flâneur is a moving character (described by Baudelaire, later taken up by Benjamin) who, without waiting for places and art to reach them as mechanical (or, more recently, digital) reproductions, travels to places themselves, recovering their auras. In this context, Albdorf calls into question a culture of indifference and immunity to auras according to which contemporary visitors of natural sites seem to travel there not to breathe the air and authenticity of the landscape, but to generate new reproductions, selfies which guarantee their presence in a famous place, not for the aura but for the possibility of producing new digital content.

The dialogue between nature and technology, analog and digital, concrete and abstract, phenomenology and statistics is taken up again by Claudia Rohrauer, who merges layers of past and present in a remote Finnish forest in an installation whose intimate architecture itself involves a multi-layer set-up of mobile plates fixed onto the wall. By overlaying different time periods, color and black-and-white film photos, and digital climate statistics, Expected Encounters Revisited disturbs the classic, linear narrative based on causal chains, demonstrating in Bergsonian fashion the interweaving of the past with the present and the future.

Following the thread uniting Fluxus discourse around taming technology (see Paik) with the trend of Tactical Media, Robert Bodnar wishes to hijack technology towards new territories of freedom. His project tackles the same hybrid species of digital landscape, which results this time in a time-lapse video installation and a photo collage made up of shots taken at different times of the day, acting as a means of timekeeping (in parallel with a discussion of the definition of photography as writing with light). The Heliocentric video installation juxtaposes two spherical time-lapse recordings, an urban and a natural landscape presenting the opening of a clearing in the woods. The videos are presented in two white rectangles placed on the floor. Despite being the only project recorded in Europe, the Timescans collage has, because of the brightness of the colors, of the mix of light and day, of the technological magic of glass printing, paradoxically, the most bizarre and cosmopolitan feeling to it, like a heterotopia, a mix between Orient and Occident.

The series of oppositions (nature-culture, hidden-revealed, earth-sky), the oscillation between day and night, and the way light is filtered by leaves in Heliocentric recall, in my mind, the old problem of revealing truth in art. Unlike the flat, one-directional perspective of scientific positivism, art reveals the dualism of truth. In a Heideggerian interpretation, the art of a paradigm unconceals its most intimate mechanisms, assumptions, and values. At the same time, art allows for the existence of an unlit aspect of the world, of a mystery that coexists with the known, complementing it. This un-tamed and un-said nature is the source of the Dionysian and of the gleaming of matter as matter, beyond functionality. This liberation of matter, termed earth by Heidegger and taken up again nowadays by the discourse of new materialism, places Bodnar’s project in a different light. It allows us to feel the earth spinning under our feet and the heavens above. We can also therefore offer a more nuanced interpretation of Guschelbauer’s half sky half earth composition, or of Höpfner’s preference for the Tibetan Plateau, where the earth attempts to meet the heavens. We now perceive the vastness of the idea of fourfold living, of that at home in harmony with the heavens and the earth.

Regarding the notion of habitation, the question raised by all these projects is in how far is the fine balance between heavens and earth disturbed by technology? The task of the contemporary photographer is again to provide a free territory for meditation, where the eye of the camera is not subservient to the workings of power. Or, in Flusser’s terms, the task of the artist is to escape the condition of servant to the power apparatus by producing their own discourse. Aware of that fact that the mirror-eye of an artist must keep vigil behind every mechanical eye (Vertov’s Kino-Eye), Bodnar, as a former student of Farocki’s, reveals the conflict between the geo- and heliocentric perspectives as a war of the world, as a clash of ever-partial, successive truths. Choosing for her investigation the space of the forest, as manifold source of interpretation and representation, Claudia Rohrauer critiques scientific linearity. We understand that both the sun and science need revolutions. We understand that the post revolution annuls any naïve, unilateral interpretation of the concept of truth.

All these projects work somehow magically. Then comes the question: whether by exercising a certain (human/camera) rhythm and motion, by breaking with linearity, the post age opens up the possibility of recovering the aura (beyond the circle of one’s Facebook profile picture). It seems we are witnessing a new kind of posthuman, technology-enhanced contemplation. Unlike the old bourgeois variety, which was critiqued by writers like Brecht and Benjamin, this one does not play into escapism. On the contrary, the technological poetics of the landscape stimulate critical thinking. The Brechtian prologue to Irina Botea’s film stands as a testament:

Ah, what an age it is/ When to speak of trees is almost a crime

For it is a kind of silence about injustice!

Translated by Rareș Grozea.

POSTED BY

Raluca Oancea

Raluca Oancea (Nestor), member of International Association of Art Critics (AICA) and European Network for Cinema and Media Studies (NECS), is a lecturer at The National University of Arts in Buchares...

www.Dplatform.ro

Comments are closed here.