Joanna Warsza’s direction for Public Art Munich 2018 is a commitment to redefining public space and developing commissioned works for a specific audience. The second edition of Public Art Munich runs in various locations around the city through the 27th of July featuring Romanian superstars Dan Perjovschi and Alexandra Pirici, philosophers such as Alexander Kluge and Chantal Mouffe, and a number of continuous programmes and events by Jonas Lund, Franz Wanner, and Anders Eiebakker. The last edition of PAM took place in 2013 organised by Elmgreen & Dragset but public reception considered the previous release to have little connection to the city and even falling victim to “plop art” and other various tropes of public art programmes. Warsza contested this notion by producing ephemeral projects in existing public monuments or places of interest. The end product of the edition will become an archive of the city composed of individual projects about contemporary and historical issues. The project is risky and bold, and while there were moments of failure even during the opening weekend, Warsza pushes curatorial stakes to a new limit.

The Polish-born Berlin-based curator opened the festival with a personal note. Taking her own position as a starting point, Munich is historically associated with the headquarters of Radio Free Europe which broadcasted over the Iron Curtain during the Cold War. In 1981 the Munich headquarters of RFE were allegedly bombed by Nicolae Ceaușescu and Russian agents. The first day opened as a homage to the historical relation between Bavaria and its Eastern neighbours taking place in the DIY church of a Russian émigré and Munich’s Olympic stadium built by Frei Otto for the 1972 Summer Games.

The first location was the illegally built “Ost-West-Friedenskirche” in the outskirts of the city. The roof was covered in metallic chocolate wrappers to achieve the effect of gold-gilded churches in the East. Architect and artist Aleksandra Wasilkowska worked with this location explaining its history and connection to post-war Munich. The park where it is built contains hills composed of rubbish and debris from the war. This served as building material for the small church. Supposedly, the glistening metal roof inspired Frei Otto during the construction of Munich’s Olympic stadium. Wasilkowska’s intervention in the church which replicates the ceiling in constant motion was underwhelming and lost amid the strange location itself – but her riveting talk about anarchic spirituality served to kick off the festival with themes of property prices, occultism, community sites, migration, and creative rebellion.

The narrative of the first day proceeded with a ritualistic procession organised by Anna McCarthy and Gabi Blum. At the end of the procession Munich’s Olympic stadium served as the site where Massimo Furlan recreated the famous game played in Hamburg between East and West Germany. The game was a victory for East Germany with a goal scored by Jürgen Sparwasser from the guest team. Furlan typically restages famous matches with minimised players while broadcasting the original radio commentary. Complications ensued during the match with the actor Franz Beil being injured and a slow response by audience and medics. Soon after an audience member streaked twice into the field while the medics were taking Beil away. The streaker and the audience’s enthusiasm were indicative of the kind of festival prepared by Warsza, one which reached out to real football fans rather than a traditional art audience. By selecting an interdisciplinary approach Warsza tapped into different populations and opened all events to the public rather than focusing on any luxury opening. Several people in the audience were in attendance because of the Olympic stadium which has not been used for football matches since the new arena was built. A group of protesters arrived at the stadium to use it as a platform against legal changes to police behaviour in Bayern – the space was activated by a buzzing crowd. Furlan continued playing the match alone to its dramatic finish in spot lit rain.

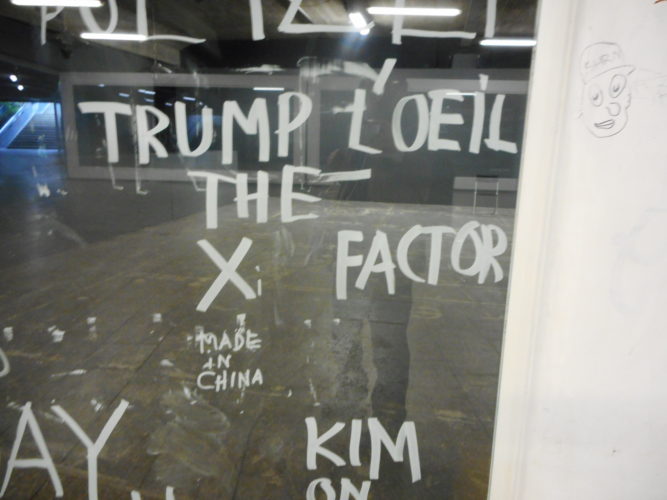

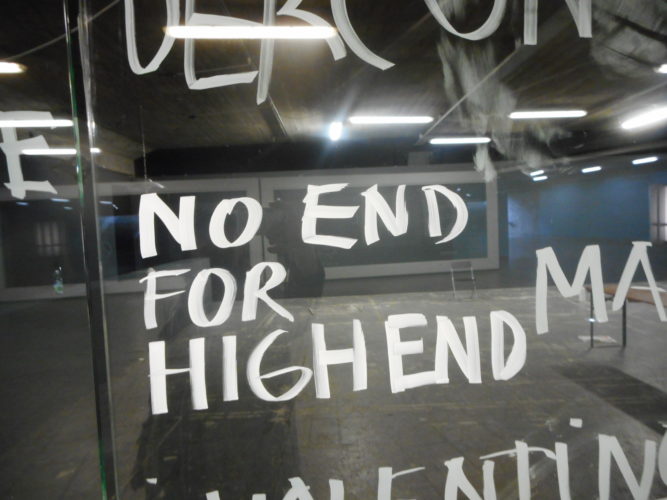

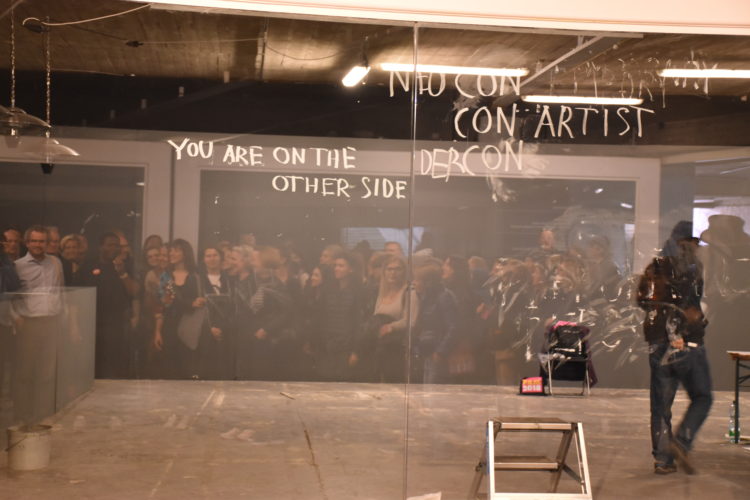

The second day started with a change of pace focusing on contemporary subjects. Dan Perjovschi performed the first of three drawing sessions while in conversation with Documenta 14 head of education Sepake Angiama. Combining critiques from the art world with everyday experiences in the city of Munich, Perjovschi’s humoristic drawings are often interpolated with dark criticisms. This session titled Labour Day took place on the 1st of May during which no visible festivities appeared in the centre of Munich. The drawing session ensued in an underground passageway in the city’s high-end shopping street. Surrounded by Gucci and luxury brands – the small underground passage is a strange phantom space in one of Germany’s most expensive real estate districts.

The last events of the opening days took place at the PAM pavilion designed by Flaka Haliti and Markus Miessen. This is the only permanent structure during the festival and is integrated in the busy central market. Artists Jonas Lund & Patricia Reed talked about a project which takes place on Facebook through the duration of PAM. The social network is a new kind of public space on which we interact with communities and receive targeted advertising. The well-timed presentation just after Mark Zuckerburg’s court case in the United States inspects online public space and the inability to opt-out.

With a variety of projects, PAM18 will continue with projects through the summer. Alexandra Pirici & Jonas Lund will stage N Football, a performance featuring youth teams from Bayern Munich which will visualise the economic apparatus behind the game. Working directly with Munich’s population and interests shows that the festival is organised with the public in mind. The interdisciplinary position of many artists also expands its reach. Inviting philosophers to work alongside architects, designers, and composers like Ari Benjamin Meyers revises what shape a Public Art Festival can take.

The political stakes are high in Munich. Faced with steep property prices and a changing legal framework that will allow instant arrests by police authorities – students and activists felt the need to insert their own narrative into the events. The public and participatory nature of the first day’s projects reflected on Munich’s unique history and offered a platform for local activists to appropriate the procession and use it as their own stage. During an awkward moment Warsza commented on the perception of Munich as a wealthy and conservative city to which Munich’s Kulturreferent Dr. Hans-Georg Küppers disagreed with a grimace. A publically funded event like PAM18 is possible because of the wealth of the region but rather than using it as an advertisement for the city’s brand or as a tourism apparatus, Warsza encourages criticism and daring projects which might play with the line of legality. This radical approach to the festival, curating, and the concept of art reverses what Elmgreen & Dragset labelled an “art safari” in 2013. The spread of activities is directed at the population living in Munich with visitors only able to see the festival in parts and catch up with documentation. Rather than working with pre-existing notions of public art, PAM18 invents it anew.

Public Art Munich 18 is on until July 27, 2018.

POSTED BY

Àngels Miralda

Àngels Miralda is a curator and writer currently based in Barcelona.Miralda is a contributor in: Rotunda Magazine, Blok Magazine, Revista Arta, Sleek, and AQNB. Catalogue publications have been ...

angelsmiralda.com

Comments are closed here.