I had been reading The Dark Night of the Soul by John of the Cross just days before being invited to the duo exhibition of Ovidiu Toader & Justin Orvis Steimer at Catinca Tăbăcaru Gallery in Bucharest. Synchronicity? Algorithm? These days, I don’t know the difference.

John of the Cross writes from a limit situation — the isolating brutality of imprisonment — a poem that has gained significance in psychoanalytic literature, as it recounts the originary trauma and how it might be traversed through language, advancing religion as a solution: a discourse of desire. In this reading, the “dark night” is not simply the absence of the divine, but a space where signifiers dissolve and the ego disintegrates in a necessary descent for reconfiguration. What forms do inner transformation and healing strategies take today, within art and culture?

Toader and Steimer operate along divergent fronts of a mutual spiritual longing, rooted in the pre-verbal self but expressed in distinct registers. Toader celebrates the maternal figure, the archaic, all-encompassing presence that precedes symbolization and language, evoked materially through vegetal forms and aquatic media. In contrast, Steimer, a New York-based artist, gives shape to the subjectivity and the particularity of his internal states through his intuition, informed by a multitude of mystical and spiritual traditions, which he translates into ambiental forms. Their works shift across planes, slipping from sculptural to flat, and blend into one another as if part of a solo exhibition, unintentionally mapping traits of a recent collective unconscious.

This bifurcation, between the maternal complex (Toader) and mystical synthesis (Steimer), reflects the polarity between affective modes of religious experience and more structural, dogmatic forms. Toader’s works draw from an aesthetic of childhood, where vegetal and aquatic forms intertwine in inflatable steel structures and objects made of bulletproof glass. In this configuration, the maternal figure takes on sacred dimensions, becoming an omnipresent icon across his works — Queen (Ant), Mother Ship, The Mother Ship’s Chest, The Flower of Life 2. The inflated metal structures assert a solid, almost totemic presence, evoking the force and impact of archetypal motherhood. His central work, Queen, gathers this mythology into a voluminous, polymorphic body whose hybrid morphology suggests simultaneously a grasshopper, a coral, and a pair of breasts — a protective-organic form with erotic and ancestral overtones. Simultaneously, the bulletproof glass pieces extend the mythology of the totalising mother in a more fragile, introspective register, reactivating the leitmotif of water in a gesture akin to a reversed archaeological process. These works explore memory as an attempt to pin it in time and space, filled with flowers from Toader’s family collection, adding a deeply autobiographical, emotional layer.

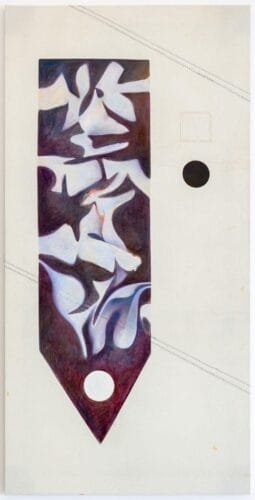

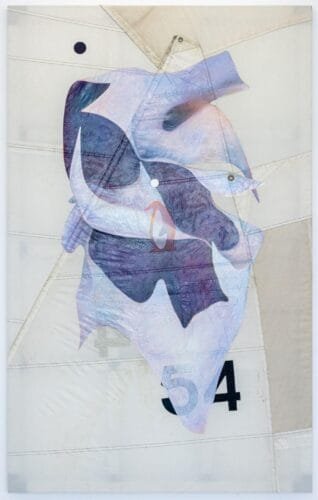

Steimer, on the other hand, describes a dilettante spirituality without a stable language. His paintings depict abstract states through floating, flowing, or geometric forms on the resilient surfaces of sailboat canvas. The painted forms resemble organs, seemingly detaching from the pulsing material, chosen with a romantic reverence precisely for the life it has already lived, bearing the traces of effort and traversal in its stitches. He invokes the sacred through gesture and atmosphere, not through doctrine. His artistic spirituality is not grounded in a fixed set of values or practices, as with traditional religions, but in a fluid assemblage of beliefs with porous boundaries, often combining contradictory or incoherent elements. As philosopher Simon Critchley notes, “mysticism is not a religion, but a tendency — a distillation of devotional practices, scriptural interpretation, theological teachings, and philosophical-conceptual reflection” (Critchley, 2024). Mystical experience does not follow a linear or analytical path; it is lateral, associative, cumulative, and synthetic. In this, we find an analogy to how digital culture functions more broadly: not as a rigid system, but as a network of intersecting, transforming, and recombining meanings.

Through our conversations, both Toader and Steimer expressed a shared interest in spirituality as a space for affective and symbolic exploration, drawing on backgrounds in Buddhism, Christianity, astrology, mathematics, and other esoteric systems of thought. Their work extends collectively, raising questions around emotional processing and experiential techniques, resonating with what Mark Murphy calls the digital spirituality of screen capitalism (Murphy, 2023). Spiritual direction has shifted under the influence of capitalist discourse, becoming a diffuse form of emotional self-regulation that coincides with digitality.

In this context, Slavoj Žižek warns of the “culturalization of belief” — the transformation of faith into lifestyle — a shift with serious ideological implications (Žižek, 2001). By emphasizing tolerance, this tendency can inadvertently depoliticise us, dampen our impulse to question or critically reflect on the values and assumptions underpinning different worldviews, reworked as lifestyles. As a result, many contemporary forms of spirituality end up complicit with the exploitative socio-economic status quo, masked as personal choice or inner search. Our individual need to be seen and addressed has mutated into a tolerance of surveillance; we have become complicit in a broader system — a digital ecosystem governed by corporate imperatives. From the technofeudalism Yanis Varoufakis outlines in the context of artificial intelligence where our labor becomes invisible, as we train and refine algorithms simply by handing over our data, preferences, habits, and emotional reactions (Varoufakis, 2021), to the rise of e-astrologers catering to a collective anxiety: the craving for affective structure in an unpredictable, chaotic world. In both cases, the same vulnerability is exploited: the human desire to be understood, to feel connected, and the tendency to attach ourselves to objects that promise satisfaction. This dynamic can also be mapped symbolically through the trajectory of belief: from mother to father, with desire as the mediating force. In this sense, the maternal image, which both Toader and Steimer evoke in different ways — the former directly, the latter symbolically — recalls the infant’s first object of attachment: the mother as source of nourishment, calm, and protection from a vaguely threatening exterior. From this foundational bond, an ambivalence emerges toward the paternal figure, who eventually assumes the role of protector, but also retains his former potentially threatening quality (Freud, 1961).

Freud saw religion as a collective neurosis, a product of unconscious desires and Oedipal fantasies, a regression in which we manage our fears and uncertainties by forming attachment to and admiring an omnipotent father figure (to replace the fallible real one). In contrast, Jung regarded religion as an indispensable part of the collective unconscious: an archetypal channel constitutive of the self. Between these two classic positions, the work of Toader and Steimer seems to propose a third path: spirituality not as revelation or neurosis, but as a cultural symptom, a digital fantasy that serves as an affective coping mechanism in the face of disappointment with what Lacan might call the “third symbolic parent”: society itself.

While Toader and Steimer do not explicitly thematise digitality, it remains an unavoidable backdrop to the cultural landscape in which they operate. In the context of “belief-as-lifestyle”, any spiritual practice today appears inseparable from digital mediation, which reshapes our relationship to the sacred in terms of visibility, performativity, and feedback. Even when not directly articulated, contemporary spirituality coexists with the digital: a new kind of divination that offers signs. Spirituality functions as a form of affective and social resilience within an oversaturated symbolic reality, one in which it increasingly dissolves. It survives primarily through ritual: a way of performing belonging, but also of reclaiming parental figures in the extended sense of the word, signaling broader social fragility.

As Žižek reminds us, the modern notion of faith as private, inner conviction neglects its intersubjective dimension: “belief entails the belief that others believe” (Žižek, 2001). You don’t have to believe personally; there’s no such thing as first-person belief because doing so would overstate the subject’s autonomy and ignore how we stage our beliefs. Today, religious belief is no longer necessarily a self-standing internal certainty; it is enacted through repetitive gestures: rituals, traditions, and customs preserved out of loyalty to family or community. In this sense, belief operates more as a logic of belonging and relational continuity. The exhibition, which came together as a spontaneous encounter, without a conventional curatorial framing and with the artists seeing each other’s works for the first time at installation, becomes, in itself, a relational experiment.

Through their respective practices, Toader and Steimer create a space for reflecting on belief, attachment, and the symbolic — themes central to understanding the affective ruptures of our time. Without offering direct answers, their artistic approach gives form to sensitive modes of traversing and symbolizing disruption, resonating across psychological, theological, and cultural registers. In doing so, they illuminate not only individual fragilities but also deeper fissures in the social structures shaping subjectivity today.

References

Critchley, S. (2024). Mysticism. New York: New York Review Books.

Freud, S. (1961). The future of an illusion (J. Strachey, Trans.). W.W. Norton & Company. (Original work published 1927)

Murphy, M. G. (2023). The direction of desire: John of the Cross, Jacques Lacan and the contemporary understanding of spiritual direction. Palgrave Macmillan.

Varoufakis, Y. (2021). Technofeudalism: What killed capitalism. The Bodley Head.

Žižek, S. (2001). On belief. Routledge.

POSTED BY

Ioana Gemănar

Ioana Gemănar (b. 1999) is a visual artist based in Bucharest, a cultural researcher, and a member of the artistic and editorial collective specula. She is currently pursuing a master's degree in Psy...

Comments are closed here.