Ioana Stanca is one of the most appreciated artists of the young generation, with studies completed at the Painting Department of the National University of Arts in 2011, a time when the local artistic production was at the end of a boom as a bubble, the first truly to be remarkable, both institutionally and in the art scene. It is therefore a period in which a heightened interest from the West in the artistic realities of the country is also foreshadowing a directly proportional, infallibly manifested interest within its borders. From producers, curators and promoters to the new collectors suddenly eager for contemporary art, it offers, however, for the first categories, the possibility of approaching the typology of the artifact specific to the global West in its production, location and distribution; in addition to the latter, it perhaps also offers the possibility of the social (status) value that the artifact and the realities of the new global cultural tourism can guarantee, or simply the unparalleled spectacularism of the contemporary artwork as an investment placement.

The artist, who at first practiced painting (realistically represented in a work from those years is a scissors on a black background, like a foreshadowing object), along with several others of the period mentioned, is among those who naturally and instinctively related to global trends, which in the context of this period meant first and foremost the adoption of new technologies in the treatment of media and/or fashionable cultural policies. In this aspect, as we know, given that she is also one of the few contemporary artists with a general audience, a context mediated by magazines such as Elle and good media coverage, Ioana Stanca was one of the first to approach Fiber Art, which has remained her main means of expression until now.

Of course, the textile medium recontextualized in the midst of the major genres, of Art, not of applied arts, has been approached before, even simultaneously within the global artistic context of the 1950s to 1970s, by artists like Lena Constante, Ana Lupaș or Ritzi Jacobi. However, in that first turning point, it was more closely related to its processes, to the discursive social possibility of these flexible and natural materials, or to the aesthetic tendencies of a New Ruralism. Ioana Stanca, who began with a similar process-orientated approach to the medium, intersecting with other practices like ceramics or performance, treats this genre in her recent works of more in the style of what American art critics have called Craft Painting, a tendency that reveals textile or ceramic materials’ intention to disguise themselves as a finished image of what painting or sculpture represented. This is often done by resorting to the aesthetics of the artifact, taking over the structural properties of the major genres by camouflaging their appearance and borrowing styles or techniques, paradoxically criticizing from within their very privileged position. This is doubled by the fact that often these new artifacts deal with socially inclusive themes or current issues.

From a genealogical point of view, the providential place that the artist occupies, like everything that has to do with initiating and then imposing something, is visible in the public reputation as well as in the realities of the Romanian artistic scene. The practice that almost singled it out between 2012 and 2015, when the term textile arts was still often used in the field of critique, is what we see pervasive today when the designation has migrated to Fiber Art. We are talking both about the private gallery space and, timidly but consistently, about public institutions. What better example, perhaps flattering/perhaps eroding, than the emergence, with increasing success and visibility, of other only-seemingly-ioana-stancas. If we take as an example the recently closed exhibition curated by Diana Marincu at the Catinca Tăbăcaru gallery, which this text with a rather long but contextually necessary introductory digression tries to deal with, it would have been enough to walk in at the same time about 6 km towards the city center, to the Atelier 35 space where another exhibition was taking place. There, you would have seen a work containing the same three compositional elements as in “Dusk” (2022): a flower(1), sourounded by flames(2) from which a female chimera(3) emerges. The flower is in both cases blue and pearly like a vagina dentata, the fire obviously reddish-orange, while the color of the chimera is the only one that differs, along with the lower level of embroidery execution, particularly visible in the rendering of chromatic gradients. This is just one example, and the name of the author in this case is less important. The responsibility, as in such other cases, I believe, lies with the institutional decision-makers of that space, while the artist has the right to create whatever they see fit. Of course, these are details to which those who tend to see the genealogy of the visual arts in a historical and material context are attentive, but certainly not relevant to Ioana Stanca, whose career is now well known internationally, both in Central and Western Europe and in North America.

Returning to the exhibition It will not be simple, it will not be long, what stands out visibly from the author’s body of work are two aspects, one formal, the other conceptual. Firstly, there is an obvious aesthetic value, that mimics the genre of painting or three-dimensional sculpture. Secondly, there is a sustained self-referential dialogue between the medium, how it is related to the historiography of art and, more importantly, to the psychosocial configuration of this occupation, oscillating towards the artistic genre, in the identification and affirmation of feminism and not only of exclusive domestic femininity, as it has been prejudiced.

Let us begin, however, with the latter direction, since it is subsequent to the overall context in which this medium imposes itself, and then discuss the compositional and formal aspects. About which, discussing with the artist when I announced that I wished to write this review, I was telling her to have been offered (something rarely encountered in the current artworld) the baroque pleasure of iconographic detectivism, and the experience of the categories of the sublime in all its valences, from horror to erotic ecstasy.

There was intense discussion about the defining moments that imposed Fiber Art between the 1950s and 1970s, in the context of today’s unanimous categorical acceptance and in relation to feminism. Individual works such as those by Leonora Tawney or Annie Albers, Annette Messenger’s soft sculptural installations, or Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party” (1979) were highlighted. Consistent with these individual moments, a theoretical and institutional framework for indexing and receiving Fiber Art in the context of art history and contemporary art, transmedia trends also emerged in the 1980s. This was particularly boosted by Rozsika Parker’s exhaustive 1984 study, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the making of the feminine. Not only did this text have a definitive theoretical influence, but it also generated an exhibition series under this brand of The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery in Women’s Lives 1300-1900 and Women in Textiles Today, exhibitions which toured several Anglo-Saxon institutions in 1989.

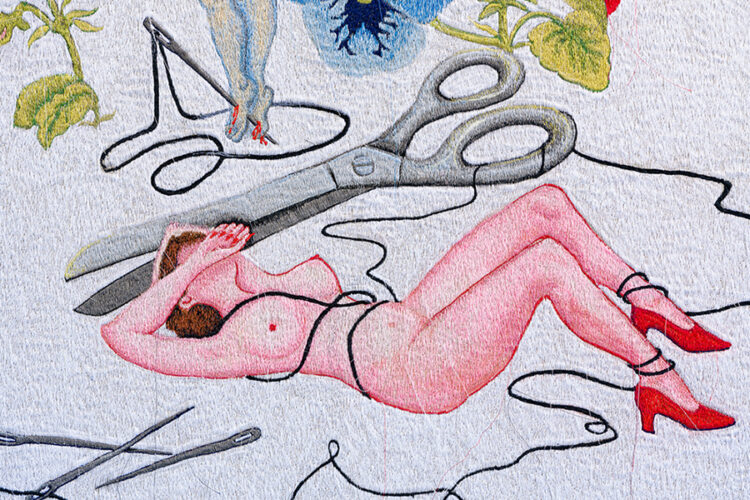

The feminism that emerges in the works of Ioana Stanca is both one of overwhelming vulnerability – with characters, almost exclusively self-portraits, always naturally nude as if they were from a world where original sin does not yet exist – a frontier of individuality and agency with a devouring presence, given by the knowledge in surreptitiousness of both the personal and the collective identity of the gender to which she belongs. On this duality, between fragility and hardness of identity, Kate Walker elaborates in one of the book’s most quoted paragraphs:

“I have never worried that embroidery’s association with femininity, sweetness, passivity and obedience may subvert my work’s feminist intention. Femininity and sweetness are part of women’s strength. Passivity and obedience, moreover, are the very opposite of the qualities necessary to make a sustained effort in needlework. What’s required are physical and mental skills, fine aesthetic judgment in color, texture and composition; patience during long training; and assertive individuality of design (and consequent disobedience of aesthetic convention). Quiet strength need not be mistaken for useless vulnerability.”

This stoicism is hinted at in the title poem by Adrienne Rich: “it will touch through your ribs, it will take all your heart/ it will not be long, it will occupy your thought/ as a city is occupied, as a bed is occupied/ it will take all your flesh, it will not be simple”. Having had the chance to observe the artist at work in her studio as well as during the exhibition making, I can confirm one less visible aspect, that of the exhausting labor that a painstaking activity with manual practice and sustained cognitive analysis, painfully repetitive and monotonous, can cause.

By practicing this kind of manual activity, we are also talking about a reaction against digitization through a return to tactile creativity, to the craft of something handmade, rematerializing experiences. We can say that we are today, in an increasingly pronounced sense, often stuck somewhere between the physical and virtual worlds, weaving through the processes of perpetual digitization that take over even the sensory systems. Thus, this mechanical work with materials among the domestic – the most natural to the body – is a form of resistance, coming from a desire for a palpable, tactile, somatic connection with the world and with others.

Interlocking these two elements, the emphasis on the material as well as the social elements is related to what has been called the “material turn” in current cultural studies. The conscious vegetal extensions, the rhizome-like compositional vines in Ioana Stanca’s two-dimensional works, tentacle all sorts of signifiers, referring to a notion of the distribution of agency through objects. They ask us to imagine things not as inert objects isolated in a non-place, but as active nodal delegates, linking and coordinating often geographically and temporally distant entities. This perspective defines a type of transnational and transcultural thinking, assuming that objects are truly meaningful not when they stand still in a void, but in a (social) environment in which they absorb context through their everyday use.

A concern with gender and domesticity is visible, an obvious interest in carnal realities. A hidden black domesticity also exists, which, like the monotony of the embroidery technique, alludes to the repetitive chores that women were traditionally considered to follow.

The iconographic elements are precisely indexed, bearing fairly straightforward meanings. In the case of the vegetation, it is composed exclusively of two plants – there are many references to dualism, to the couple – anthurium (popularly known as “Cupid’s plant”) and pansies. These derive their name from the French penser, thus referring to the duality of instinct and intellect, of Dionysian and Apollonian, of experience and analysis. The poignant sexuality of the anthurium is suggested in its very form or through intra-species personifications, as in “Ever Sharp” (2023), where the erectile pistil fecundates like the human-spermatic. As a shape, the two flowers fit together like Lego pieces, as you can imagine.

As for the fauna, it is composed exclusively of insects such as butterflies or ants, and spiders. One might say hidden animals, micro animals of the ground, or animals of the air, perhaps a reference to how the condition and identity of women has been treated throughout history. Similarly, the same duality persists here; the social ants are clearly symbols of the rational, of structure and order, while the spider that thrones protectively in the three-dimensional space of the gallery, as well as the two-dimensional ones spread out all over, are references both to the Bourgeoisesque mother-spider and to arachnids in general, as imagined beings of horror from our collective nightmares. Pollinating butterflies are the linking element of these two extremes, fecundating and more than often being eyelids self-portraits.

There are many references to the Renaissance. I think that what one can detect at first glance without getting close to the works is a certain atmosphere akin to the quattrocento, given by the omnipresence of cobalt blue or the indefinable mystical light of pure white. In “Big Spider” (2023), the arrangement of the eyes on the back of the nine-meter spider is a reference, like the blue mentioned above, to the ceiling representing the Constellations in the Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva (Rome). In “Ever Sharp” the character falling towards an oversized pair of scissors makes a gesture similar to the angel in Michelangelo’s “Annunciation”. The scissors on which Ever Sharp is inscribed, although it may seem like another iconographic reference, is in fact the mark of an actual object the artist uses in her studio. In the array of typical period figures, a female St. Sebastian in the agony of grace, depicted in the work “Martyr” (2023), also appears quite obviously.

And because we are talking about the Renaissance, the continuous thread, both represented as a whole and as material, are also symbols of the narrative. The way it is paneled, with the spider in “Big Spider” weaving all the other works-entities on the wall, on the ceiling, or emerging from behind the pillars or from the corners, also suggests a narrative.

In addition to this adapted symbolism, we are also dealing with an abstract, biographical one. For example, in “Big Spider”, the two eyes on the head, together with the six on the back, refer to the artist’s birthday – 26 – as well as to the date of the opening. Again, a celebration of a conscious identity.

Another aspect that is immediately apparent in the two-dimensional works is their anchoring, the frame, which as in other earlier series by Ioana Stanca, is a compositional stand-alone element. It is made up of elements complementary to the composition – arms, pins – which more often than not protectively “embrace” the scene, keeping it tucked in. The same typology is involved in the treatment of the structural metal frames that support the soft sculptures, those personified scissors of an human proportions, also supported from behind by protective arms. The soft sculptures, be they scissors, spiders, or flowers, are embroidered with something that should take the place of a confessional poem instead of a mouth and as something that should register, be witnesses, eyes situated in clusters with biographical references.

In conclusion, I can personally say that since Ioana Nemeș have I encountered an artist with such a personal symbolism and practice, superimposed on an vernacular mythology that constructs a psychology of the small states, domestic and anxious-neurotic in its DNA, subscribed to an immutable narrative, Bogomilist in moral value, and expressed in such powerful reiterations that transcend the specificity of the medium.

The exhibition It will not be simple, it will not be long by the artist Ioana Stanca, curated by Diana Marincu, took place at Catinca TABACARU Gallery from April 26 to July 15, 2023.

Translated by Liliana Popescu

POSTED BY

Horațiu Lipot

Horațiu Lipot (b. 1989, Alba Iulia) is a curator and cultural journalist. As of 2021, he works as an independent curator, collaborating with venues either from the ON or OFF art- scene in Bucharest, ...

Comments are closed here.