Before coming to Gheorgheni, I searched for information about the festival and couldn’t find anything.

The festival is indeed quite hidden because it doesn’t take place annually, sometimes not even every two years as we agreed on at the beginning – we don’t have a regular budget, the festival is done by projects, every edition is rethought financially and usually the funding is announced quite late. In this edition, our luck was that AFCN [local funding body for culture] announced the following year’s funding in the autumn, which was extraordinary. In January we already knew that we had a budget of 50.000 lei, in the previous years we only found out in June.

Has the project always been funded by AFCN?

When the budgets were quite large, the funding was done through AFCN. In 2012, when CNDB [the National Dance Center in Bucharest] took part in the festival, they provided us with funding. Being a Hungarian theater, we also have access to Hungarian cultural funds; however, the foundations in Hungary rarely finance Romanian festivals, they would rather fund theater or dance productions than big projects like a festival.

The festival started in 2006. How come you decided to organize it in Gheorgheni?

The Figura Theatre, which hosts the festival, is the only one in Romania which has a founding statement containing the expression “experimental theatre”. The theatre became an institution in 1990 (when Andrei Pleșu was the Minister of Culture). A small amateur experimental theater company, containing engineers, intellectuals, ordinary people, a community built around Bocsárdi László managed to create one of the most interesting theatre companies in the country, in Gheorgheni, gaining a professional status. Since then, Figura has been continuously reformulating their relationship towards this imperative to experiment and innovate. This need explains our interest towards the contemporary theatre theme. Since the beginning of the 2000’s Figura has included dance-theatre productions in its repertoire, beginning to work with choreographers such as Vava Ștefănescu, Péter Uray, Yvette Bozsik, Dénes Döbrei, Gábor Goda, these being choreographers who created shows focused on movement with actors from Figura. The dance.movement.theater festival was founded in order to sustain this new project trajectory. Its role was first of all to promote this kind of art, displayed through shows, it was also intended to act as a platform for exchanging values between the dance/movement theatre scenes in Hungary and Romania: to bring valuable shows to its stage and at the same time offer space for presenting shows created by local creators.

What is your public?

Our public is very special. I told you about Figura – this company appeared in 1984, it was strange then, and it still is now, but because of the 2 festivals – dance.movement.theatre in the even years and Colocviu, the minorities theatre festival, that gathers Hungarian, Yiddish, and German companies from Romania, in the odd years – and because of Figura’s repertoire, an unique public was formed, one that is quite cultivated. Colocviu presents over 20 performances, throughout the 10 days of the festival, and the dance.movement.theatre festival brings 8-10 production to Gheorgheni that are presented over the 5 days of the event. Many collaboration possibilities appear, we have contacts with ensembles and theatres that, knowing the generous public, return to Gheorgheni, they choose this city over others if they know they are going on a tour in our proximity.

Do you have ties with, for example, the contemporary art scene in Sfântu Gheorghe, with Magma?

We are friends, of course. I was born in Sfântu Gheorghe and I spent my my high school years in the same atmosphere as the three founders of Magma, one marked by the AnnArt festivals and by the events organised by the art scene promoters of the region. The theatre in Sfantu Gheorghe (born out of the Figura company, in 1995, when 8 actors and the director Bocsárdi László moved from Gheorgheni to the Tamási Áron theatre) was a promoter, a reference point in the contemporary art world, a place that influenced the whole cultural scene of the city.

You have certainly heard of the project European Capital of Culture 2021. Sfântu Gheorghe was the center of this proposal. It ran in the name of this region, that is made up of small cities, not very far from each other, 50-60 km away; the entire area is around 150-200 km long from North to South. In the theatre domain, there are institutions in every city, with very special artistic programmes, theatres that develop their own festivals: Gheorgheni has Colocviu and dance.movement.theatre, Odorheiul Secuiesc (through the Tomcsa Sándor theatre) has a contemporary dramaturgy festival focused on Romanian-Hungarian cultural exchanges, Miercurea Ciuc (the Csíki Játékszín Theatre) organises one of the few children’s theatre festivals in the country, and Sfântu Gheorghe has three festival formats with an international impact: Reflex Festival, PulzArt and Flow Fest. Therefore, there are many events of this kind, in a very small area.

Did the ECoC application enable you to acknowledge all these ties or were they already functioning?

The project team traveled a lot through all these cities, they collected many projects and ideas. A lot was gathered from the public and many projects were proposed by ordinary people. Although the initiative was not successful, as we didn’t qualify to the 2nd stage of the selection, a very positive atmosphere was created, discussions regarding the cultural scenes of the region being created, a dialogue that was missing from our day to day discourse.

Is the cultural life part of the society? For example in Bucharest, people are complaining that no one cares about the city’s ECoC application.

I can’t exactly tell, when it comes to our situation – anyway, culture has a pretty small impact everywhere in the country. If you take a look at the statistics, you can find out that people don’t often go to the cinema – but the number of spectators is increasing every year. There are no cinemas in Gheorgheni, people have to go to Târgu Mureș or Brașov if they want to see a movie. It’s the same with theatre: we have to manage the quality of our offer, as well as its impact, work that we have to do with the community that hosts us, the way in which we shape society.

To what extent is culture integrated in people’s lives?

The problem of the non-existent public is present here as well, the public that exists but doesn’t come, or comes for something else. We make a pretty special kind of theatre, our shows are considered heavy by the local public, but we have a devoted public of about 400 people, they are the ones who see every show no matter its success. We try to be consistent and search for some kind of honesty, one that no one is immune to. I believe that the honesty of an actor’s presence or the validity of the artistic proposal are the only things that can attract the public to theatre. If the show transmits energy, anyone who enters the room (with or without prejudice) will be touched by the show. This should be our main target: to dismantle this invisible barrier between the public and the stage, to gradually build an audience for the theatre that we believe in.

How did you chose this year’s shows? What are the criteria? Does each edition have a different theme?

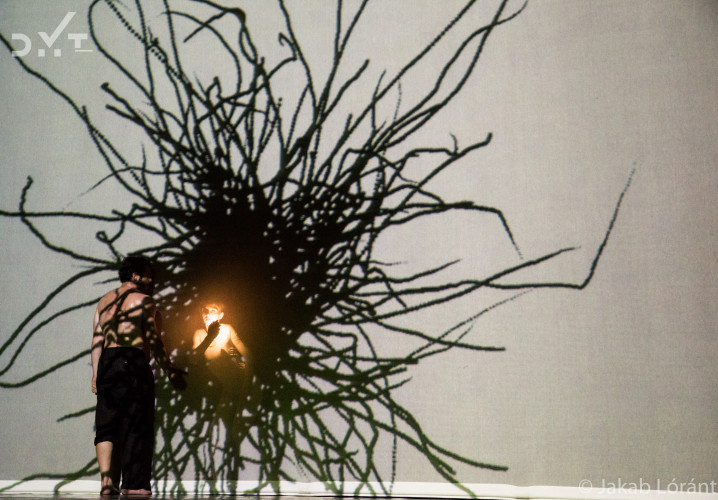

Until 2012 there was a different theme for each edition, but this year we gave up this idea. We wanted to gather new and valuable Romanian and Hungarian pieces. Thanks to the funding that we received, we succeeded to present a very valuable programme, and as a headliner, we displayed a very important show (at an international level), “Birdie” by the Pál Frenák Company.

In Bucharest at CNDB there is an ongoing debate between 2 directions: the one regarding movement, and the so-called conceptual one, regarding discourse. In the festival’s selection there is a big focus on movement and the body: is this choice deliberate?

We search for valid offers and proposals that have coherence and intensity, that can transmit energy. I originally worked with the dramatic theatre, narrative/spoken/dramatical/textual theatre. I watch dance-theatre as an observant spectator, paying attention to what I am interested in: the ability of a show to transmit energy. However, excellence in the technique of movement is an essential quality: it is the medium that has the ability to get the message across to the audience , it is the way in which a dance composition can radiate energy.

Do you have a good relationship with CNDB?

Yes, we discuss quite a lot. I told you that I had an idea – bringing dance productions to Figura’s repertoire. In the last three years we haven’t done our own dance projects, we have abandoned this direction, although unique creations were produced with our actors. With them, a show created by a choreographer has another currency, it incorporates more of their art as actors and less from their dancing technique, a skill that a “dramatic” actor cannot completely master – although this aspect was worked on. I believe that it is important to resume this path, in another format, thinking about the institution not as a permanent ensemble that assigns work to its employees, but thinking about our resources as a production unit. My idea was to launch a project for independent companies, an open call in which Figura acts as a co-producer: it doesn’t include its own actors in productions, but it offers space and financial resources to an ensemble that creates a show. Like a residence that ends with a show that can be displayed on other stages.

Is the cultural centre a space where things happen, where people meet?

The way that I see the theatre’s mission: we somehow have to transform the community, to offer a valuable cultural offer, one that is worthy of a big city, but to also accept more popular events, so that other sections of our public are not marginalised. We have a very open space, that has the ability to generate a permanent flow of spectators through the diversity of the offers. Figura has a theatre repertoire – new or invited productions, the cultural centre is in charge of music (classical or jazz), folklore and art, so many varied events happen under the same roof. The infrastructure consists of a big room (370 places), a studio of about 60-80 places (depending on the space that a show requires), a small exhibition space and other rooms used for rehearsals.

Is it a place where people meet?

The bar where we are right now is a place where young people meet. In each city, such a place is of an extremely big importance. The way that you spend your time, where you can go out, what you can find there and what energies are transmitted in those places are very important aspects.

Does Gheorgheni have a mainly Hungarian community?

Yes, our community is 85% Hungarian, 15% Romanian. Our public is mainly Hungarian and even the Romanians in Gheorgheni speak Hungarian.

Do you look towards Hungary in your choice of productions?

We are far from both Hungary and Romania, we are located in the centre of Romania, but we are very hidden in this mountain area. We have very few contacts with the (dramatic) Hungarian theatre scene. We have more contact with dance ensembles, contemporary dance companies from Hungary, thanks to the festival. In Romania, everything we do is unnoticed, although our focus should be to create productions that are as close to our goals and to our set of values, to be contemporary, to have European values and to be honest in our messages.

What is the relationship between Hungarians and Romanians in the community? In a recent visit in Târgu Mureș, the tension between the two communities was striking for me.

This is a cause of the wounds produced in the 90’s, on a physical/material level and on a spiritual level. Blood was shed there, both communities being affected by the conflict, even in the present. In Târgu Mureş the relationship between the two communities is probably the most problematic in the area. In Gheorgheni the problem is different. The proportions are different and there are other dimensions of cohabitation. Here you can notice that this is an underdeveloped region, a more rigid, alpine, cold community, with values that are born out of these qualities: a reduced distance between people, a certain warmth throughout the community. It’s a different group of people that we have to work with, as a theatre.

Does the festival have an educational purpose?

Our aim is to display values and productions that are good, to create the possibility for people to forget about this grey concrete, about the cold that lasted until yesterday – spring has come and the atmosphere is changing. What I have felt here is the way in which the old industry has created the city, it raised its status from small town of about 5.000 inhabitants to one of 25.000; many moved here from the region, then the industry dissapeared, but the people stayed hoping to find happiness; many found it in other countries, they moved to Germany or England. The generation of 18-35 is almost completely missing, you don’t see young people that are not in high school or that don’t have children yet. They go to Cluj or to other countries, to university or to work.

Wouldn’t this be the public of an experimental festival? So then what is the age of your public?

Teenagers in high school, and adults over 35. I believe in the purpose of culture, of theatre and public events, to bring something to the quality of life. I feel the need of an contemporary art gallery in the city. I believe that our aim as a theatre and local cultural mediator should be to turn this city into a cultural space that can compete with a bigger city, and to create a quality of life similar to those in big cities. I am not talking about the standard of living (that can be quantified), but about a certain side of the quality of life: what you can do after coming home from work in the evening, what programme you are offered, what values you are transmitted.

How many times a week can people do something in the evening in Gheorgheni?

The average is 2-3 times: Figura tries to achive this through theatre, other providers also have something to offer. The target would be 15 events per month, out of which we can organise 8-10, the rest are concerts, meetings with the public and other events. We organise many events in studios, with the spectators on the stage.

Is it possible for the public to interact with the actors? To have discussions?

We have a project for students in the area of educational theatre: activities of initiation in theatre and shows in the classroom. We have a programme that consists of three stages, we go into classrooms and present a show, the students come to see it and then we organise a small workshop through which we discuss the problems and themes presented through the play. In the last edition, we had a professional that applied this programme to our shows, doing these 3 stages for our entire repertoire. Besides this, we try to bring as many shows that are specially created for high school students, that can be done in classrooms and that present issues that aren’t usually discussed in theatre or in schools. Next week we will have a show from Budapest from the Cultural Káva workshop, called “The Statue”, a play inspired from real events (the series of assassinations committed against various Roma families in 2008), that gives us the opportunity to analyse our relationship with the Roma community.

Is the Roma community a problem here, too?

The Roma community is a problem everywhere in Eastern Europe. In every village or city, there are Roma people or poor people who are marginalised – mentally and physically, through the separation of space, as they live in different neighbourhoods as well as through their relationship with the majority. It’s like we are living in two separate worlds. The schools in the area are segregated, and because of the problem regarding leaving the educational system, Roma children are often excluded from society, perpetuating this vicious cycle of poverty and marginalisation.

Do you believe that a play like “The Statue” can have a social impact?

I believe that it can have an impact over the majority, who is in fact responsible for the segregation and exclusion of this community.

In Bucharest there are many initiatives of community theatre, for example Replika. Have you ever had shows from them?

I have very little knowledge about this scene, as Figura has little contact with the Romanian independent theatre movement. The few contacts that we have were created through last year’s festival. David Schwartz’s “You didn’t see anything” was the opening of Colocviu in Gheorgheni. I was glad to have such a show in our festival. Colocviu is a festival in which we try to to speak about and through minorities, and for a long time, the festival only featured Hungarian and German plays, and some other shows from the Jewish State Theatre in Bucharest. I was very glad to hear about shows related to other communities, especially the Roma community, with which we probably relate most poorly. “You didn’t see anything” is not necessarily about the Roma but it transmits a relentless message regarding a “normal” person’s aggression towards the marginalised, about the exclusion of some, from our world and about the ways in which we conduct ourselves around certain categories of people.

What was the impact of the show?

People exited silently.

The other project that we were glad to have received at the last edition of Colocviu was Mihaelei Drăgan’s “Del Duma – tell them about me”, a show of profound honesty, received with much enthusiasm from the public. Another event, that goes against the concept of minority festivals is “Double Bind” by Alina Nelega and Réka Kincses, at the Târgu Mureș National Theatre, Liviu Rebreanu company. Through these projects, we managed to turn the minority festival status into the main theme of the event.

Do you think that there is a positive value to being marginalised? Nowadays, the idea of taking power out of this condition is discussed a lot. Especially that such position might offer you the opportunity to rise against the domination.

There are more and more discussions regarding the marginalised communities, but it is still hard for us to build new relationships with them, relationships that are more powerful than our majority attitude: a certain level of tolerance, of curiosity, of the way in which we position ourselves in relation to the unknown.

Being marginalised can offer you something – when you are so low that you can’t go lower, you have a more powerful position from which you can fight back because you don’t have anything to lose, or you are in a permanent opposition with the status quo.

The status of an artist is always one of a minority. But it is this status that forces you to find your own “present time”, forcing you to express yourself eloquently and speak about what and how you think and perceive. To always be aware of the truth you wish to express and that you want to communicate to the community.

The festival „dance.movement.theatre” took place at Teatrul Figura in Gheorgheni between May 18 – May 22, 2016.

Text translated by Ana Avram, who was an intern with Revista ARTA in June 2016.

POSTED BY

Cristina Bogdan

Founder and editor-in-chief, between 2014-19, of the online edition of Revista ARTA. Co-founder of East Art Mags, a network of contemporary art magazines from eastern and Central Europe. Runs ODD, a s...

www.evenweb.org

Comments are closed here.