Last year on the 21st of September, I was happy to support artist Kristin Wenzel in the production of her latest exhibition in Bucharest The Near and the Elsewhere, which took place at the Dinamo Swimming Pool. The choice of space was representative of Kristin’s interest in urban social infrastructure and her artistic engagement with the public sphere. Framed as a site-specific and site-sensitive intervention, the exhibition opening included a book launch and a DJ set by Borusiade (Miruna Boruzescu).

Kristin Wenzel is an artist and currently lives and works between Bucharest and Gotha. She studied sculpture at the Düsseldorf Art Academy, where she completed her master‘s degree in 2013. Her multidisciplinary practice involves large-scale installations, sculptures and interventions in public space, often created as site-specific and site-sensitive social environments. The notion of transformation, be it conceptual or material, permeates her entire practice and connects the past and present through processes of collecting and reinterpreting. Born and raised in Bucharest, Romania, Borusiade started dj-ing in 2002 as one of the very few female DJs in the city’s emerging alternative clubbing scene. Influenced by a classical musical education, a bachelor in film direction and fascinated by raw electronic sounds Borusiade combined these universes in the construction of their DJ sets and starting 2005 also in their music production.

Five newly commissioned glass works were placed around the terrace of the pool. Adorned with sand and cast out of sea glass collected by the artist at the Baltic Sea, they reflected the artist’s relationship to water, as well as her longtime engagement with architecture and memory. The publication launched during the event documented a large-scale installation of the same title, created in 2020 at Suprainfinit Gallery.

Later in the autumn, Kristin and I sat together and reflected on the project, discussing Kristin’s ambition to break with the boundaries between art and everyday life, and her understanding of exhibitions as places of shared experiences and open communication. The interview below is a friendly conversation, a way to think through public space, art, and the exhibitionary format. From walking as a psychogeographical practice to exhibitions as live encounters and activators of memory, we invite the reader to reflect with us on the role of artistic and curatorial practices in urban contexts and communities.

Your archiving of Bucharest’s decaying architecture through fallen stucco ornaments, under the framework of (Re)Collection, has been on-going since 2018. Can you tell me a little bit about how it started, and how you extended it in the framework of the Dinamo Swimming Pool intervention?

(Re)Collection is probably the first work I did after moving to Bucharest in 2017. I found the first fallen ornament in April 2018 on Batiștei Street by default – I was just walking around. Walking in the city was actually my daily practice back then. For me it was a way to engage with the city I just moved to and to discover it. Every day, I would walk in a different area, just randomly. On one of those strolls, I found a fallen ornament and I decided to take it home. Back then, I thought ah, that’s such a nice present from Bucharest! It felt as if the city and I were communicating somehow. This is how it started, and then, of course, I began to pay much more attention to fallen building ornamentation and I found them everywhere. There’s also this thing – if you focus on something, of course, all of a sudden, it’s everywhere.

For the intervention at Dinamo swimming pool, I recast five ornaments out of this collection in sea glass, which I collected in 2020 during a residency at the Nida Art Colony in Lithuania. The pandemic started while I was there and my daily practice was again to go for walks, mainly on the beach. During these walks, I first looked for amber, which can be found on the shores of the Baltic Sea. At some point I switched to collecting sea glass because it proved to be more promising. For the exhibition at the Dinamo swimming pool, I had the idea of using this glass as a material. Somehow it made sense to me to connect these two places and collections.

What I find really intriguing about the genesis story of the five ornaments is how walking was involved as an artistic research practice at different stages of the process (from the city to the sea). Walking emerges as a way of experiencing and studying space from this very quotidian perspective, rather than involving some cartographic technique.

Yes, I am very interested in psychogeography, a practice that focuses on the exploration of urban environments in particular, without a specific route. The term psychogeography originated in Paris in the 1950s and was first coined by the Situationists. It emphasizes the emotions and the personal relationship to space. I see walking as an artistic practice, especially when it is done consciously and without a plan. That’s how I discovered the ornaments, through this very intuitive approach of just walking around, without a destination, and choosing my paths according to what strikes me at that moment.

Another important aspect of your practice with regards to urban environments is how you often create installations in off-spaces, such as disused kiosks or flower shops, and now the public swimming pool. Can you tell me a little bit about how you explore these other architectural elements of urban space?

I think my attention towards disused architectural structures as well as to public spaces that are not directly connected to the art world comes from the same source of curiosity. If you are interested in architecture and walking around, discovering places, I think the question of where you want to be discovered as an artist pops up. I always liked the idea that one can see art in public space by default, without for instance having an explicit interest in art, or aiming to see an exhibition. It’s nice to run into something unexpected.

In Bucharest, I feel there are a lot of architectural structures in-between use, small empty spaces, and gaps. In my mind, I find this very contrasting to Düsseldorf, for example, where I studied and used to live before. In a city like Düsseldorf, everything feels very settled and finished, somehow. Bucharest is shifting and changing all the time. It’s also a question of – do you feel empowered to actually shape a city? This is what I enjoy about working in the Bucharest context. Of course, I ask myself a lot why I do art, what it brings to me and what it could bring to society at large. By intervening in public space I feel like I can do something that is valuable not only to me, but also to other people.

At the Dinamo outdoor swimming pool I wanted to create an event where people have time to engage with the space, to observe rather than do an activity like swimming. An exhibition is not only about what you show as artworks, but also how you show these works and where. The intervention at Dinamo was about declaring the entire space as part of an exhibition and inviting the audience to stay with it and experience it.

I think something that really encouraged people to experience the space was the musical contribution by Borusiade. Listening to their music really transformed the whole atmosphere and felt very personal.

When I thought about the event it was clear to me that music should be involved in order to create a space where your mind can wander in different directions. It encourages people to behave differently from how they would act in an exhibition. The collaboration with Borusiade was very exciting. I told them at some point that I wish they could hear themselves play. The way in which the sound travelled from the terrace down to the pool was really magical.

It’s interesting how you conceptualised The Near and the Elsewhere as at once an exhibition, an intervention, and an event. From the start this made me think of the exhibition format more critically. It questions what an exhibition should do and how you relate to space in an exhibitionary context. If an exhibition is an event, then it becomes a living thing, an encounter between multiple entities and practices, understanding not only art but also curating as beyond an institutional practice.

To create an exhibition as a living thing, as you called it, is very important to me. Some people were a bit lost when they arrived at Dinamo, because they didn’t really understand where the exhibition was, and no sheet of paper was explaining it. The sculptures were aligned around the terrace of the pool, and one had to move around to discover them as well as the space itself. A couple of people told me that they felt uneasy in the context of the pool at first, but then they said it was amazing when the music started and they let go of these preconceived ideas about what an exhibition is and how to behave in it. When you drop them, something happens. A party or just a social event can also be art.

In this context, I think it’s important to mention the first exhibition I showed at Suprainfinit Gallery in 2020 entitled The Near and the Elsewhere. For this exhibition I recalled the swimming pool where I learned how to swim in my early childhood in the GDR. It was the first time I put into practice what I had been reflecting on for many years – that the installation itself, the sculpture itself, is the whole exhibition space. I wanted to break down these kinds of boundaries: this is the space, this is the installation, there is something on the walls. To drop this division between the art, the space, and how you move in it. I envisioned an installation that fills the entire gallery space, and as soon as you enter the gallery, you are a part of it. I changed the way you entered the gallery by building a high platform. The visitor had to walk up and then down into the pool, with the entire gallery space being the basin of a swimming pool. The central piece of the installation was a water fountain, while scattered around the installation were various ceramic objects that referenced the fallen ornaments from my collection.

As part of this exhibition, I invited the artist and composer Simina Oprescu to give a small, intimate concert within the installation. Her piece about the sounds of water, using field recordings of underwater sounds and splashing water, was the last thing I was able to implement during the exhibition before I left for the aforementioned residency at the Nida Art Colony, and just a few days before the total lockdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

I am really sad that I didn’t see your show at Suprainfinit in 2020! The event at Dinamo built on it in such a fascinating way. This time, at a ‘real’ pool, but without having access inside it as you did at the gallery exhibition, each iteration produced different spatial restrictions on the format of the exhibition. But the event at Dinamo also referenced the Suprainfinit show directly, through the launching of your new artist book.

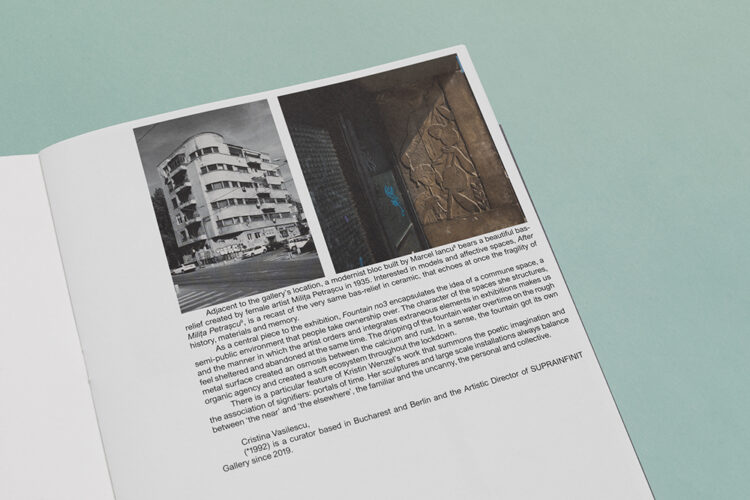

For me the event at Dinamo felt like something had come full circle. The artist book, designed in collaboration with Alin Cincă, covered the installation at Suprainfit Gallery in 2020. It was accompanied by a text written by Cristina Vasilescu, where she elaborates on my artistic practice and how it relates to architecture. The cover shows a bas-relief by Milița Petrașcu located at the entrance of a modernist apartment building designed by Marcel Iancu, situated in the proximity of the gallery. A replica of the very same bas-relief was also part of the exhibition at Suprainfinit, and the area where both are located has an important emotional significance to me. The same goes for the Dinamo swimming pool and its surroundings. I discovered it with friends when I moved to Bucharest and I spent most of the summers of 2018 and 2019 there. It’s also a special place architecturally speaking, referencing a latter point in the modernist architectural history of Bucharest than the Milița Petrașcu bas-relief. It was built in 1963 and never renovated. The whole Dinamo sports complex was connected to the then recently developed neighbourhood in the area, planned in such a way that it had a thorough social and cultural infrastructure for the inhabitants (including a park, schools, and cinemas).

As it was built as a competitive swimming pool, there is a public grandstand for people to sit and watch the competitions and, in the context of the event, the stand became a place where people could reflect and sensorially experience the space. When you entered the exhibition in 2020, you could also sit on the edge of the pool, i.e. on the sides of the installation. And during the whole opening it was crowded with people. The fact that one had the opportunity to sit within the installation meant that people actually spent more time inside the exhibition, talking to each other. Generally, at openings communication tends to take place outside the space itself (and usually over a cigarette).

To me, the whole project emerges as addressing personal and collective memories, from the public swimming pool of your childhood to the Suprainfinit Gallery exhibition and the gallery’s neighbourhood, from the Dinamo swimming pool to the beach walks at the Baltic Sea. How do you relate memory to space and to the built environment in your artistic practice?

Yes, the recollection of memories is the reason why I called the project The Near and the Elsewhere. Everything you mentioned is already in the title. Memories are blurry. They are close to us because they are filled with stories from our personal lives, but they are also somewhere else, intangible–especially when moving from one context to another. Memories are often connected to certain places and times. In the context of the historical events of 1989 and the still on-going transformation processes, these memories and feelings of people, especially those from the East, have been quite overlooked. Many buildings and places that had meaning for generations were demolished, disappearing silently. So what happens to memories when those places no longer exist? I have been thinking for some time now to start a research and exhibition project about memories that have become placeless. The swimming pool in my hometown, where I learned to swim as a child, was demolished in 2013. The Near the Elsewhere project, with its various formats and means of expression, was also a way of dealing with this loss. Losses are part of everyone’s life, whether it’s the little things we’ve lost somewhere along the way, a certain place that no longer exists, or a loved one. And we often have to cope with this alone. As an artist I see it as a privilege to be able to turn those losses into images, to find a visual representation, to talk about them–to transform them into a sculpture, an installation, or a book.

POSTED BY

Maria Persu

Maria Persu (born 2000) is an independent cultural researcher and a member of the editorial and artistic collective specula. She is currently working as a curatorial assistant at Suprainfinit Gallery ...

Comments are closed here.