The exhibition “Wisdom in the Absence of Power Structures”, curated by Georgia Țidorescu as the result of an annual prize awarded to emerging curators by Kunsthalle Bega, is more than a critique of the Anthropocene and a successful collaboration with five accomplished visual artists: Miriam Austin, Floriama Cândea, Ioana Cîrlig, Lera Kelemen, Marine Nouvel. At a deeper level, the undertaking also opens a reflection on novel modes of being-in-the-world, on alternative forms of dwelling and relationality that transcend hierarchical structures and the linear, progress-oriented thinking upheld by late neoliberal capitalism.

Inspired by the philosophy of the mycelium (Yasmine Ostendorf-Rodríguez) and the phenomenology of the vegetal (Michael Marder), the curator thus adopts a stratified, multi-layer structure in which the works in the gallery – akin to wild mushrooms, whose ambivalent allure (pharmakon) couples remedy with danger – represent only the fruit, the mysterious reproductive organ, of an underground network of thin filaments that span kilometers, connecting different instances of an entire ecosystem. Aligning with the curatorial paradigm of care, prevalent in the Asian context, a paradigm that favors the generation of authentic relationships over the mere production of objects, the project initiated by Georgia Țidorescu cannot be understood apart from the deep substratum of the curator’s relationships with the artists, as well as the artists’ with a number of researchers from diverse fields such as biology, technology, philosophy, or sociology.

Therefore, “Wisdom in the Absence of Power Structures” is not merely an exhibition about plants and fungi, but rather a project that calls for applying, in life and in artistic practice, principles drawn from the phenomenology of the vegetal and the non-hierarchical, distributed ontology of the mycelium. The works do not aim to didactically represent species of fungi, plants, or animals, but instead to probe new perspectives on time and spatiality, on death and toxicity, and, not least, to imagine ways of reconfiguring the art scene according to the principles of collaboration, decolonization, nonlinearity, activism, and sustainability.

One of nature’s first lessons aims to abandon the quantitative, mathematical simplifications of spatiality and duration. To look at a living tree, to investigate a mycelium entails a processual relation with the qualitative, immeasurable time of life itself, as well as an understanding of the phenomenon of invisibility. To truly see a tree or a plant – in itself, for itself – thus means patiently following the inherent process of germination, the budding of shoots, the falling of leaves in autumn, it means being aware of the existence of roots, of the importance of the bond with the earth. Such an experience entails reaffirming care as the essence of the human, in keeping with the well-known phenomenological formula of “letting things be”, as well as a refusal to submit to the frantic pace of the present in the era of digital capitalism.

To this end, we can decipher the delicate presence of Lera Kelemen’s works in the exhibition: a cocktail dress composed of metal watch cases (only so much adrift to brace my self control, 2025), a sword inlaid with crystals extracted, likewise, from watches (an object sits on your table, waiting to be picked up, 2025), a sinusoidal wave of crystal glasses that bear traces of lipstick and drinks, encapsulating dilated moments of exhilaration and affective intensity, irretrievably lost (bracelet, 2025). Time, death, and memory are approached here with lucid melancholy, from the perspective of archiving, of the artist as a collector of objects, memories, moments. The longing to archive is thus connected, following Derrida’s suggestion in Mal d’archive: Une impression freudienne, with the anxiety of death. The watches, as well as the Dionysian moments sealed in transparent glasses, recall that the archive is at once eros – the desire to preserve–, and thanatos, a species of death, a strategy for fixing the living in a static form, a way of freezing memories, of transforming experiences into documents.

The discourse on the fragility of life and the impossibility of reducing it to an equation is taken up by Floriama Cândea’s installation, Neural Bloom #2 – My Breath is Someone Else’s Air (2025), a rhizome-flower with countless stems, a white bird with a hundred arms, a hybrid being that uses technology to help humans relearn how to look at raw, elemental nature. Leaving behind any scala naturae, together with the principle of verticality and the rigid dichotomies mind-body and artificial-natural, the relation is articulated through similarity and difference, calling for a slow movement of regression toward that arche, the originary point of the world that makes possible any becoming-plant and becoming-animal.

Subtly harmonized with the robust white beams of the Kunsthalle Bega gallery, and inspired by photosynthetic species from the Danube Delta (reeds, water lilies, etc.), organisms that maintain balance within their ecosystem, the work sets in motion a phenomenological investigation of air as an element of deep continuity between human and world. Its leitmotif is breath itself: a phenomenon in which air reveals itself as a bridge between body and environment, between viewers, the gallery space, and the flux of life. Viewers are invited, more precisely, to interact with a sensor that translates their breath into the movement of the white branches, generating an Apollonian dance of technology with the organic. Invisible and often ignored, air is thus “exposed” as a common medium, visible only through its effects on things, as a symbol of the interconnection of all living beings. The exhibition experience thus transcends static contemplation, transforming the visitor into an active participant: each breath alters the space and highlights the fragility of the balance between human, nature, and technology.

The work thus functions as a miniature ecosystem in which the subtle interaction between breath, air, and physical structure reveals hidden rhythms of life and the importance of sensitivity in perceiving the natural world. Through this bridge between the visible and the invisible, between the biological and the technological, between individual and collective experience, the work becomes an exercise in awareness of the interdependence of all forms of life under the new motto “I breathe, therefore I exist”.

Nature’s wisdom is further revealed by two works by the French artist Marine Nouvel: a floor-mounted installation and a video placed right at the entrance to the gallery, whose slow tempo has the cathartic effect of preparing and resetting the mind before entering the exhibition’s heterotopic space. In this sense, in Foucault’s terms, the space of the project “Wisdom in the Absence of Power Structures” presents itself as an “other space”, a “space of deviation”, one that undermines reality, short-circuiting conventional hierarchies and social norms.

Entitled La Pudeur des Mycètes (2023), this video presents a slow choreography in which three female nudes appear and decompose within a living tropical forest setting. Digital manipulations and the intensity of the colors invoke a vaporwave register, with its inherent melancholy and uncanny eroticism. The sustained yet extremely slow rhythm of movement recalls plants’ capacity to suspend vital processes to avoid expending energy: vegetal torpor. Philosophically explored by Bergson and, more recently, by Michael Marder, this phenomenon of vital latency can be read both as an anti-capitalist manifesto against all “fast” tendencies in society and art, and as an invitation to probe the complexity and nonlinearity of organic time. In this sense, the work recovers the non-quantitative dimension of time from the rhythm of breathing or of cell division, from the infinite slowness and perseverance of mushroom growth, as well as from the extension of the mycelium.

The way the movements of the nudes follow the pulse of the organic world lays bare the body as a space of communication, invoking that phenomenon of the chiasm, of reversibility, which Merleau-Ponty describes as the strange moment when the forest or the landscape looks back at us, as a pouring of our flesh into the flesh of the world.

The second installation, a glade with algae and mushrooms made of resin, clay, and glass, takes on the role of activating the body. Placed low, at ground level, it operates gesturally, inviting each viewer to bend down, to transpose themselves to the height of the mushrooms, to become-fungus, and to experience how they look at the sky. The scenario is, once again, uncanny: a world inundated with water, at the threshold between extinction and renewal, where Astrida Neimanis’s hydrofeminist phenomenology operates. All living beings are aquatic bodies. Our body is composed of water, and water circulates and connects us with other bodies, species, ecosystems, with the elements and with nature itself (Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology, 2017).

The dissolution of the human must once again be read not as a death, but as an outpouring into the flesh of the world, as a Deleuzian becoming-nature, as a posthuman entanglement. The boundaries between species dissolve: mollusks meet fungi, humans merge with algae. The new liquid life calls for new hybrid forms, our watery remains entail a mixture of blood, flesh, chlorophyll, the human and the nonhuman.

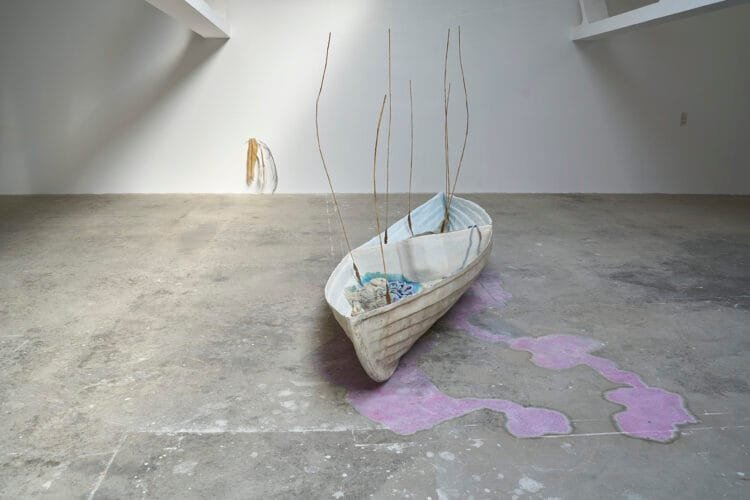

Along the same affective-visceral line are the works, both Dionysian and Apollonian, in the SEAXBURH (2025) project of British artist Miriam Austin. A beached boat, at the bottom of which lie two figures in silicone mixed with minerals collected from marshlands along the rivers Po (Italy) and Great Ouse (England), is thus joined by a series of objects that combine sharp metal pieces with organic materials and diaphanous garments. Complementing these, a video reimagines the legend of Saint Æthelthryth, a mythic Anglo-Saxon figure whose body is said to have been miraculously preserved in the swamps of eastern England, setting it in parallel with the fate of the eel, a species on the brink of extinction, once so numerous as to shape the economic life and beliefs of communities.

Inspired by history and myth, by the symbolism of the boat as a space of passage, heterotopic, as well as by the miraculous preservative properties of silt, the project treats the marsh as a living climatic archive which, as it sequesters carbon, accumulates sediments that hybridize geological traces with cultural ones. The legendary time of Saint Æthelthryth thus composes itself with the natural time of the eel, and with that of water and stone. The discrepancy between the finitude of history and human memory and the geological time of rocks, the eternity of the natural elements, once again calls for a posthuman recalibration of the relation between human and nonhuman.

A similar critique, addressed simultaneously to anthropocentrism and to the naive attempts to reinterpret nature in a romantic key, as a virginal space of individual contemplation and refuge, is put forward by Ioana Cîrlig’s photographic project, The New Empire (2017- ongoing). As the title suggests, the project is inspired by the ecofeminist thinking of Vandana Shiva, an activist writer who exposes an entire chain of imperialisms and colonial mechanisms, applied to the vegetal world as well. Founder of Navdanya, an Indian movement for ecological agriculture and seed freedom, Shiva links the politics of monocultures of sugar, cotton, tea, rubber, or coffee with a “monoculture of the mind” that underpins all imperialisms and illusions of superiority of a species, race, religion, or gender, prompting separation from exploited inferior entities.

Through her unique way of bringing plants to the foreground, thanks to both her anthropological interest and her novel aesthetic choices, Ioana Cârlig in turn challenges the colonialism of the vegetal world and the patriarchal vision of the world, grounded in control, fragmentation, and exploitation. Her consistently intimate, personal approach, the force of color, and the close-up transform plants – whether rare orchids, uncanny albino poppies, or resilient weeds and simple garden flowers –, from resources into subjects, from accessories into protagonists.

In this context, The New Empire, a project initiated in 2017 and still ongoing, explores the ever-shifting and often paradoxical relationship with nature. Originating as the artist’s personal inquiry, having grown up in a block of flats in the city, where “water comes out of the wall” and vegetables are picked from supermarket shelves, the research involved an initiatory journey through national parks, botanical gardens, forests, and beaches. Along the way, Ioana Cîrlig documented places and endangered flowers, and met people from whom she gradually learned how to approach plants and how to look at them. These scientists, who strive to slow the decline of ecosystems, frequently appear in the images, usually in the background, surrounded by vegetation, dwarfed by it, or with their backs turned.

In the Kunsthalle Bega exhibition, a distinctive place is held by plants photographed in the midst of a struggle to survive inside transparent plastic casings. Against a dark background, their vivid green shines triumphantly, illuminating the composition suspended in a void that philosophers would associate with that dense “nothing”, with Being itself. Their uncanny beauty, which fuses fragility and force, evokes the way Schopenhauer defined the vegetal realm as the purest embodiment of the “will to live”.

The photographic series mounted on the wall is accompanied by a few velvet veils suspended from the ceiling and by a video, all featuring macro images in electrifying colors, obtained, paradoxically, without any digital manipulation. It is, in this sense, a genuine revolution of the vegetal, an outpouring of force and eroticism, a manifesto of plants that refuse to be treated as colonial resources, exploitable entities, and objects of imperial knowledge.

This manifesto is supported in turn by all the projects included in “Wisdom in the Absence of Power Structures”. Plants, fungi, natural spaces, the entire sphere of the living demand a critical framework that recalibrates the power relations between human and nonhuman. Taken as a whole, the exhibition does not offer a harmonious experience in which the human may be redeemed alongside nature, on the contrary, it calls for the radical dissolution of anthropos as well as of the inherent power structures. The experience of nature as pure alienation does not, however, undermine our relation to it, but establishes the ground of our raw, wild being (Merleau-Ponty). Flesh helps us perceive the human at the fundamental level of organs, of particles, thereby accessing an ontology prior to the split subject –world, spirit–body. The wisdom invoked will be one of deep continuity, where dream meets madness, the Apollonian is twinned with the Dionysian, and becoming-machine makes possible becoming-plant.

Translated by Dragos Dogioiu

POSTED BY

Raluca Oancea

Raluca Oancea (Nestor), member of International Association of Art Critics (AICA) and European Network for Cinema and Media Studies (NECS), is a lecturer at The National University of Arts in Buchares...

www.Dplatform.ro

Comments are closed here.