The exhibition “Utopia and Research. The Timișoara Experimental Groups 111 and Sigma (1966–1981),” curated by art historian Ileana Pintilie, together with Andreea Palade Flondor at the National Museum of Art in Timișoara, is an extensive research project dedicated to these major experimental artists of Romanian postmodernism. Over time, Ileana Pintilie has produced ample historical documentation: from exhibitions, specialized publications, and books dedicated to these groups. Starting with the historical exhibition “Creation and European Synchronism. The Timișoara Art Movement” in 1991 at the Timișoara Art Museum, in which Group 111 and Sigma occupied approximately one floor, alongside other local artists influenced by them (Peter Jecza, Romul Nuțiu, Gabriel Popa, Ciprian Radovan, and others).

This exceptional project includes works by Ștefan Bertalan, Roman Cotoșman, Constantin Flondor, Doru Tulcan, Elisei Rusu, and Ion Gaita from the 1966-1981 period, arranged chronologically and contextualized alongside a series of documents which belong to the artists, private collections and the museum’s archives, .

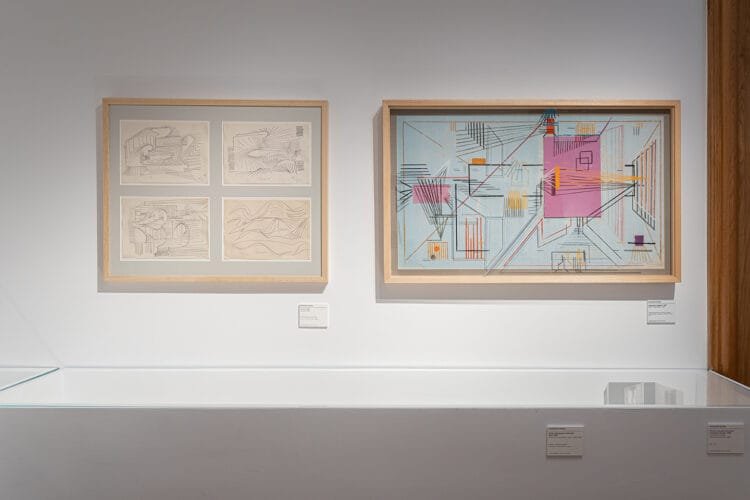

The first three rooms are dedicated to the works of the 111 Group (Ștefan Bertalan, Roman Cotoșman, Constantin Flondor), and on the walls of the first roomwe see the abstract-geometric explorations that preceded their emblematic works of optical art. Two of which are present here. Made of slatted glass, one belongs to the museum and the other is part of Flondor’s personal collection (Undulating Mirage from 1968).

The name 111 was symbolic of the artists’ individuality, as they signed under their own names, but wanted to debut as a group in order to gain greater visibility (see for the same reason modernist Romanian group The Group of Four). The three discovered Paul Klee’s catalogs and books (which they translated themselves from German) and the informal painting style (Art Informel), the group making its debut shortly afterward at the Regional Salon. Following their graduation in Cluj and Bucharest, Bertalan and Flondor arrived at the Art High School in Timișoara, where they dismantled their academic training (or rather, rebuilt it from the ground up) and gravitated towards the study of nature and science. Although Cotoșman was trained in theology (graduating in 1963 from the University Theological Institute in Sibiu), his abstract collage experiments in the first room (based on photographed paper, glued to eachother) demonstrate both confidence and a desire to keep pace with his two peers, who constructed geometric compositions by hand.

In the second room, we find cabinets dedicated to preparatory sketches of other works in the exhibition and pages from sketchbooks, alongside a photograph of each artist and a work by Flondor (Space Organization, 1967) playing with the superimposition of glass and paper, reminiscent of Duchamp’s La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même.

The third room is dedicated to some very large and impressive pieces with which they participated in the Constructivist Biennial in Nuremberg in 1969, where the Eastern European presence was noted and praised in the local press.

After Cotoșman left to Germany (and then the US), Bertalan insisted the group formula must continue. As young artists continue coming and teaching at the local art highschool, they were being recruited to work for various periods under the umbrella of the new Sigma Group, formed in Flondor’s studio in Timișoara’s Roses Park.

Thus, we enter the exhibition part dedicated to Sigma, with a radical change in artistic practice, oscillating between preserving artistic individuality and diluting it through joint efforts and work with students. The exhibition continues chronologically, highlighting different key moments in the group’s career, as well as major themes they addressed: the “Art and Energy” exhibition at the New Gallery in Bucharest, 1974; the installation Inflatable Structures exhibited at the UNESCO Fine Arts Week, Bastion Gallery, Timișoara, 1974; geometric structures (1972-1976); nature as an artistic process; Sigma pedagogy.

As Bertalan begins teaching architecture, the convergence of science, play, nature, and technical drawing materializes in large-scale constructions, many of which remain unrealized beyond the sketch stage. Motifs such as soap bubbles, cauliflower, and other garden plants are abstracted at a macro scale and transformed into visual signs. Archival images document expansive interventions in nature (Action at the Timiș River, Sigma, 1976, or the work Membrane in the Green Forest, Timișoara, created by Bertalan based on the study of the jimsonweed in 1976) as well as happenings organized by the group or conducted with students in summer camps. The rooms dedicated to nature-inspired works stand as a compelling demonstration of curatorial mastery.

This exhibition, is already the fifth to be organized in Timișoara in recent decades (we recall “Creation and European Synchronism. The Timișoara Art Movement” in 1991, a group exhibition of Timișoara artists at the local Art Museum curated by Ileana Pintilie; “Sigma: Cartography of Learning 1969-1983” as part of Art Encounters, Timișoara 2015, curators: Alina Șerban, Andreea Palade Flondor, and Space Caviar; “1+1+1 and SIGMA” in October 2020 at MNART), in addition to those organized in the country and many others dedicated to its members.

Each time, a remarkable collective effort recreates the history of the group, giving new generations access to an essential part of post-war Romanian art. In the absence of a permanent exhibition from the museum’s collection, such reconstructions become the only form of active memory. This exhibition is, perhaps, the crowning achievement of a life dedicated to this field of research: Ileana Pintilie has devoted her entire career to documenting the art of Timișoara, following the artistic evolution of her peers, artists whose work she has exhibited and about whom she has written a extensive bibliography, similar to other art historians such as Magda Cârneci or Adrian Guță about the ’80s generation.

Museums in Romania seem to be increasingly affected by precariousness: the lack of both human and financial resources has transformed these institutions into ghosts of contemporary cultural institutions. Most of the time, they can only offer artists and curators the walls, with cultural professionals being sent to apply for public funds on their own, as they are supported either by galleries or collectors in the best-case scenario. This leaves room for mediocrity. Among the exceptions were those dedicated to Victor Brauner and Constantin Brâncuși, organized with the support of the Art Encounters Foundation as part of the “Timișoara – European Capital of Culture” funding. As I noted in 2023 in my study on artist-run spaces in Timișoara, the hope of the local scene was that the financial aid offered on the this major event would lead to lasting local investments (the conversion of abandoned buildings into art spaces, investment in heritage buildings that can host events of international significance).

In Central and Western Europe, even in small towns, an increasing number of museums have adopted a less fragmented approach, closer to current transhistorical perspectives, and have permanent sections dedicated to modern and contemporary art alongside classical art. The renewal of our country’s museum heritage leaves much to be desired: the public acquisition program has only recently been resumed, but its logic is to buy “a few from many” rather than “many from few,” without a coherent strategy for building contemporary heritage, and there are no initiatives to encourage donations to museums. Countless European museums, large and small, have adopted the American model of a board of collectors who, in exchange for prestige, education, and representation, purchase art for their respective museums. Examples include the boards of the Tate Modern and Centre Pompidou museums, of which the Timișoara collector Ovidiu Șandor is an active member. The money is there, but a lack of interest and long-term vision at the local and national levels is hindering the real development of museums. Public funds have had positive effects through grants and independent projects, but museums continue to be underfunded and dependent on the initiative of external artists and curators.

The situation of the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Bucharest is emblematic: part of its collection is literally “locked up” in the permanent exhibition, visually accessible only through bars, and some are dismantled in pieces, without labels or basic information. Many Romanian museums have remained to this day indebted to the “central model” of the permanent exhibition at the Art Museum of the Socialist Republic of Romania, built around the four pillars of national painting: Theodor Aman, Nicolae Grigorescu, Ioan Andreescu, and Nicolae Tonitza, exactly as they were conceived at the time of their founding.

In Germany even in very small towns, we find permanent exhibitions featuring living contemporary artists such as Gerhard Richter or substantial collections from the Leipzig School (“New Leipzig School”), while in Romania there is a lack of continuity. But, let’s not just talk about the richest country in Europe. The permanent collections of the National Art Museum in Warsaw include over 2,000 objects, which were acquired immediately after the museum’s establishment in 2005 with funds provided by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage and the Warsaw City Culture Office. The museum’s permanent collection also includes: the archive of The Exchange Gallery / Exchange Collection, an independent art gallery founded in 1978 by Malgorzata Potocka and Jozef Robakowski in a private apartment; and the archive of the avant-garde art gallery Foksal Gallery. In addition to its permanent collections, the Budapest Museum of Art organizes major temporary exhibitions in collaboration with the world’s leading museums (last one “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell – William Blake and His Contemporaries” in partnership with Tate). The Contemporary Collection of the Hungarian National Gallery has gathered Hungarian artworks from 1945 to the present day, which are available in the permanent collection.

Instead, our national museums have few to no resources to organize events at European standards. It is not surprising that the major recent museum exhibitions in Timișoara were made possible thanks to private funding: galleries, foundations, collectors. Sadly, the Sigma exhibition will not remain on permanent display. Even though it contains a large proportion of works from the museum’s archive that entered its collection thanks to the exhibition organized by Ileana Pintilie in 1991, when donations from artists made up for the lack of public acquisitions.

Without the constant efforts of local galleries and NGOs, which produce catalogs, publications, and exhibitions from their own funds, the museums would remain completely inactive. Instead of permanent exhibitions of local contemporary artists, museums across the country continue to organize temporary exhibitions to which artists are invited to bring their works, without any support for transportation, production, accommodation, or even a photographer – and in the end they are required to donate a work. It is a harmful practice, perpetuated by a non-existent funding system and a disregard for the work of living artists.

It is likewise noteworthy the museum failed to produce an exhibition catalog. The thin brochure published by the West University is itself a symbol of contrast: between the excellence of the curatorial work and the institutional failure of the museum that houses it. In the absence of such a document, Ileana Pintilie’s curatorial work – rigorously grounded, built on decades of research and collaboration with the Sigma archives, the Jecza gallery, and Andreea Flondor – remains insufficiently valued.

Ultimately, “Utopia and Research” is not only a retrospective of the 111 and Sigma groups, but also a mirror of the cultural situation in Romania: a system that survives through individual (often unpaid) initiative and the dedication of researchers and artists, despite the total absence of a coherent museum policy.

Translated by Andrei Mateescu

POSTED BY

Gabriela Mateescu

Gabriela Mateescu is a Romanian artist and author who lives and works in Bucharest, working with video, installation, drawing and performance. Her work is feminist, autobiographical and self-referenti...

spam-index.com/