The return of the avant-garde

I will start with a short confession: I went to see the exhibition Lay me down across the lines with a rather skeptical attitude about what is political in queer art in the Kunsthalle space in Timișoara. I was wondering what another investigation focusing on gender and sexuality can do, given the increased gentrification of an expensive city that seems to serve international clients rather than its own people. I got into the exhibition, and I think I was hanging around the first installation, a territory in which a trans artist calls the viewers to explore the limits of what a normal body means. I was aimlessly walking around when I overheard a conversation where a person was trying to figure out how to pronounce the artist’s gender. What was fascinating to me is that they were oscillating between him, her, and even a form of “it”, which to me suggested an alien form that was troubling, but also called them to ask what they were seeing. They seemed confused and unsettled in their use of the language.

When I witnessed this performance, my first reaction could have been to say “transphobia” and perhaps challenge their ignorance. Yes, the trans artist they were discussing, Sasha Ichim, is vital to understanding transgender politics in Romania, and knowing the pronoun is a first step in this direction. What I found fascinating, though, was that the two viewers were caught in a linguistic puzzle, an inability to make sense of the installation by using a word, which reminded me of Tristan Tzara and Isidore Isou’s avant-garde politics and language experiments. In Tzara’s Dadaism, what was powerful was the avant-garde’s anarchist intention to attack linguistic conventions and question aesthetic categories. In Isou’s lettrism, I was left with the idea that classic film no longer problematizes a politics of the image, and Isou uses auditory dissonance to provoke the questioning of film technique.

The exhibition in Timișoara is a return of the avant-garde in many ways, which I will discuss below, but what struck me was how the viewers got caught in recurrent confusions. I realised that the performance of “confusing pronouns” destroys all sort of taken-for-granted conventions, and I was glad to see the anarchist and avant-garde effects of transgender politics. In addition to linguistic effects, what the exhibition directly does is to question the category of aesthetics and the formal conventions related to what art means. And it does so by demanding that art be reintegrated into life. The trans performance (as it disrupts binaries), or the witch performances, enter in the category of repeating gestures of destroying traditional forms, but also speak to the desire to address directly what real life is[1]. The requirement to reintegrate art into life is theoretically linked to trauma, to the wound of living in this world and the possibility of a cure.

As the space for a non-transphobic, non-racist, non-gendered world does not yet exist, or better yet, it barely exists, the aim of the exhibition is to summon guests from a queer-feminist utopia: they must acknowledge and transform their wounds caused by stories of racism and inequality.[2] In short, the invitation of the exhibition is: lay down with us across our traumas, and maybe you’ll start to change.

The way I see it, in Valentina Iancu’s curatorial imaginarium, a group of activist-artists, who’ve started a healing process for themselves and for others, put forward a transformative and progressive femininity in order to change the world. The tactic used is titled “radical softness”, and the spectators are invited to interact with the guest performers and artists in order to change their own relationships with the hierarchies and histories of the violence we find ourselves in. My goal in this review is to discuss how their theoretical project can gain urgency, sharpness even, if it is related to what Boris Groys calls the mission of art, of interrogating the conditions of its productions. To transform the world– in this case, to heal it within the imagined space – it must be seen how the avant-garde object is included in the world as is and in a history that is not just about abuse, but also about liberating potential.

The question I will attempt to answer is: can the neo avant-garde approach the past in a different way, so that its radical intention will gain more friends and comrades?

Healing as an avant-garde project

To understand Lay me down across the lines, we must begin with the simple statement: avant-garde states that the present is insufficient and traumatic, but it can also performatively work on this given condition. Avant-garde always arrives too late or too early in the present, but this is precisely where its potential lies. The Timișoara art show is a break and, as such, the importance and outcomes of the intervention are permanently postponed, akin to a temporal lag that comes in contact with a wound that hurts. The problem with avant-garde is that the radical gesture of negation is based on rejecting the world. This is why avant-garde is never efficient or understood when it occurs, because it challenges the symbolic order. But rejecting the present world is also a mode of postponing temporality, and so the avant-garde can also mean healing timing, reclaiming the radical gesture and taking it in another key and another context with new desires.

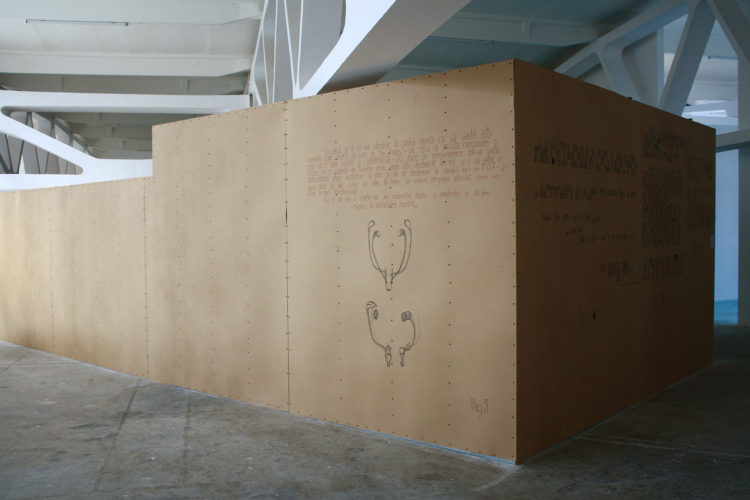

The neo avant-garde project is based on the idea that the context of artistic practice should be canceled, and from this point zero, a new world must be created. For example, here in this space hosted by Kunsthalle Bega, the initial context of a socialist factory, or a world that offers social ground for the exhibition, is radically erased in order to be filled with installations and objects that gesture to a new imagination. But I think the avant-garde can do so much more. The artist who desires a new world must share the situation in which the intervene, must share its fate. An honest act of artistic intervention is one that is not different from the people and things it speaks about and is caught in the very same world it is criticizing. This is why the history of places and people where healing is required must not be only traumatic, but also a resource for creating a comrade-like, less abusive world.

Allow me to clarify so that you, my reader, will understand how I saw the practice of healing in Lay me down across the lines. Yes, the problem of gentrification and art’s role in the process is key for understanding its possibilities. But what I mean to say is not that the exhibition is already sold out, that it’s just another capitalist product, so hasta la vista, done. We hate it so we won’t go see it. All art spaces rely on a system of transforming objects into commodities, and the solution for this shouldn’t be refusing to exhibit or abandoning visibility. But the issue with this art show lays in terms of who is called to be healed and what history vanishes along with this call to a better world. If new racist and genderist men are called to be healed, then the aim of the installation has been met, and perhaps they will feel different after taking part in the show. Avant-garde, as Clement Greenberg puts it, is attached to the bourgeoise through a golden ombilical cord, because it denounces it as a philistine and engages in a tense dynamic of patron-employee. But this is not the only possibility for the radical gesture of refusal. It should not be necessarily linked to racist and genderist men. If the people in question have other histories, perhaps one of marginalization stemming from socialism, or perhaps an experience of equality, than healing can be a political act or one of extending a hand, of a gesture of solidarity when faced with this loop in which we are all caught, from different positions.

In other words, what I want to say is that neo avant-garde needs to show that it is aware of its position in the gentrified world of Timișoara, which pushes the poor, the Roma, the anarchists and the rebellious, the hated objects of socialism outside capital circulation. The exhibition can find friends in this world, and less in imagining that it speaks to the new racist and genderist man. Here, trans politics and the political possibilities of witchcraft can become sharper, become direct, more relevant and shrewd interventions.

Transformation

Sasha Ichim’s performance, placed at the beginning of the exhibition, is the entry key into the possibilities of healing. In a radical act of self-exposure, the trans artist takes of his clothes along with the spectator in order to question what constitutes a normal body. Here, the exhibition’s project reaches a point of maximum intensity because it is caught between two tendencies. First of all, the space where the trans person becomes vulnerable together with the other must be one of safety from abuse. This performance, perhaps the bravest of the entire show due to its real time exploration of limits, must somehow be removed from the real world, a transphobic world, and turned into an installation, meaning a conceptual way of creating another world. The new world is produced here and now in the radical act of encountering a trans body. At the same time, the installation should not be completely caught off from outside intervention, and only with the corruption of the spectator can a new world begin. In other words, for the transformation to take place, there must be a tension between controlling the intervention and the real possibility of violence.

Here’s the catch: how can one be affected by the world, be thrown into the flux of permanent transformation, but also show how difficult it is to act? The trans exercise is akin to Kate Bornstein’s desire to have an identity as a transformative act, where desire in itself is an act of transformation. After all, as Judith Butler would say, trans for Sasha Ichim or Aris Tureac shows that the direction of transformation from male to female (and vice versa) means not only to refuse the binary frame of gender, but also accept that transformation is the meaning of gender. Yet, as a barrier, if the space is transphobic or anti-trans, then the possibilities of imagining healing come from radically denying the past. As an example of this radical move, how are the lines (related to the Eastern experience) that artist Elana Katz makes on their body not just traumatic? How do they also have the potential of showing unimagined artistic and political possibilities? The potential was not so clear in this performance, or at least, I haven’t seen it.

If transformation is directly linked to the place in which it is produced, the Sasha Ichim’s performance calls other friendly histories for help. What is liberating to me is that the politics of healing took place in the frame of a former socialist factory, which as a project, emerged from the avant-garde and moved in the direction of changing the world to make it equal. The trans project in Romania is already part of the history of bodies and architecture that comes from socialism, as the note in the exhibition explains and also mentions that Sasha and Patrick climbed the Transfăgărășan as a project of collective transformation. Overcoming the false opposition between workers (as people of socialism), socialist architecture (workers factory), installation (as a project for social transformation) and trans artists (as people in current capitalism) could lead to highlighting some common traits related to a broader history of struggles. But the trans-worker opposition cannot be interrogated unless the exhibition is more open to the possibilities that exist at the place of intervention and to calling new comrades to realize the neo avant-garde project.

Guilt

The border between trauma and healing is important, and the main connection can be made by investigating guilt. Where is the public placed in relation to the traumatic past? How is the public to blame and what is its potential for transformation if it feels guilty it is not queer, trans, Roma, or that it does not hold a political femininity in the Romanian context?

To answer these questions, we are asked to place ourselves in various artistic projects. The experience laid out by Mihaela Câmpeanu is that of the historical memory of the Roma Holocaust and slavery, which are part of a historical trauma buried in Romania. In order to reach the intensity of a certain pain, the artist presents a barbed wire as a place of memory. Guilt is also part of the iron bridle of Ileana Pascalău, which talks of the pain of bodies mistreated to abandon a certain femininity of revolt. Guilt appears in what Katja Lee Eliad proposes us to see, in playing with tarot cards with the goal of rejecting feeling guilty as a way of relating to the past. When the exhibition explores blame, I believe we have two important directions. There is room for theoretical and conceptual movement between Eliad’s incisive statement on what the majority does with the minority: “blame games lead to the impossibility of healing”, and Câmpeanu’s idea that guilt originating from trauma can be a resource for memory, for actualizing a lost potential of history.

We are between the barb wire, the iron bridle and the tarot to imagine other path for imagination. What can you do with the guilt within this space?

As a viewer, I was provoked to answer the question, but from an auditive and affective point of view, I admit I chose the path that was less related to my own individual blame. I wanted to take the route of the tarot (deterritorialization) and while I was walking around the exhibition, I could hear the hammer of a worker who was near this former factory, and I was pondering about the value of the on-going work of an artistic intervention. Following Katja Eliad, I wanted to seize other possibilities that might come from a certain rejection of contemplating trauma. I remembered how last year I saw a Roma woman get insulted in public and how a whirlwind of curses came hurling from her towards her abuser made me happy. I wish I could have seen those curses visually in the art show, the interpellations that shape another map of possibilities in front of your eyes, all related to immediate and effective interventions. For a second I wished I could do that, reach a direct and political liberation like I saw in articulating a curse and move beyond the call to feel guilty or mistreated.

Liberation

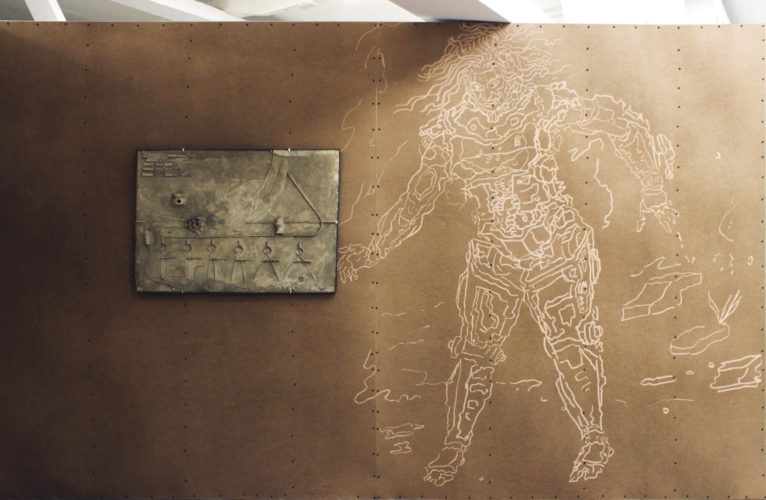

In the show, if an installation is used in order to reach a certain trauma, access can happen in two ways. In the trans performance, the public was invited to work with corporeal trauma in order to touch a reality that is usually hidden in discussions about bodily transformation. Here, one can see plastic surgery, pills, ultra-visible body modifications. In other installations, the reality of trauma is reached in a different way, by pushing certain illusions to the extreme. If, for example, this is done with witchcraft, divination or working with a certain material that transforms, illusion must be produced in order to reveal what cannot be said outright. For instance, new conceptual, illusory and phantasmatic maps could point out more clearly how liberation is possible by working with trauma.

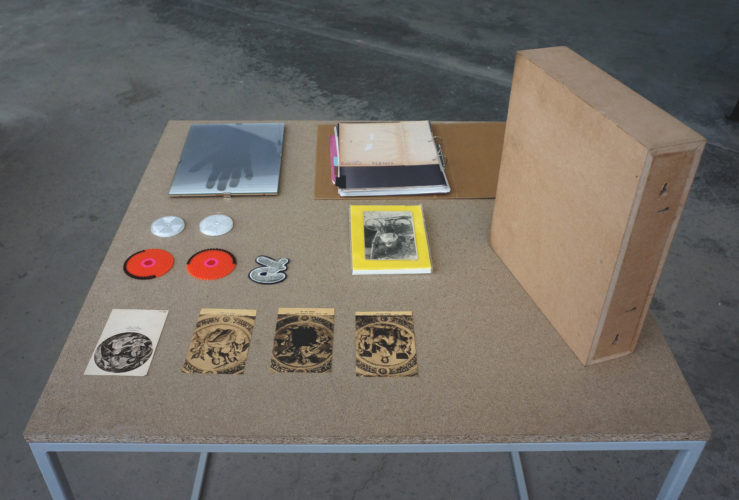

In Hortensia Mi Kafchin’s intervention, trans is a way of thinking how another grammar of knowledge is possible and how divination also means transforming reality. In Alexandra Ivanciu & Anastasia Jurescu’s installation, sisterhood is transformed into a relationship that is no longer binary, and thus seen as a relationship between two typical female bodies, but a dialectic for creating a new, yet undiscovered, entity. For Virginia Lupu, the act of pouring tin is a practice that takes on the form of the fear of the one gazing, and so exorcism can lead to a braver spectator. Transformation can also lead to liberation. Roberta Curcă’s reflective rosettes suggests other ways of containing the feminine body’s fear of wondering at night. A sign for visibility, a sign for technically marking a body. As a way of representation, the rosette is tied to the artist’s family history, but also is a mark for personal safety. Here, the rosette is not so different from the trans projects, where the body is also a product of a technics oriented towards change. Just like Roberta Curcă’s objects, Yishay Garbasz states that there is liberating potential in engaging with family history. In turn, as opposed to the strange trope of Auschwitz tattoos, the artist proposes we see how the number inscribed on skin, similar to that of the surviving mother, can lead to the sensation of power. The visibility of a sign that can be touched comes into direct conversation with the reflective rosette, but also with Adelina Ivan’s textile art or the anti-commercial objects made by Smaranda Ursuleanu, who rejects the body as a feminine commodity. In this case, in relation to a material that produces another kind of subjectivity, be it numbers, rosettes, textile objects or anti-beauty standards, change can be made and the viewer is addressed to follow it. Unlike the tactics of new maps or divination, sowing (Oana Vainer) proposes the idea of transformation through reparation, as a way of producing an object that can help with transformation. Vainer’s object interrogates the boundaries of national identities, and it stiches them.

Where to avant-garde?

From what I can gather, healing seems to become more and more the political act of a queer-feminist avant-garde interested in creating a new world. As I was called into the project, I want to see myself as part of it, and I think the spectator is invited to perceive themselves in new and surprising directions. The neo avant-garde Lay me down across the lines takes the themes of classical avant-garde in a new reading. It produces a political problem different from the one in the past, and for example, the exhibition challenges its audience to wonder about the potential of working with gender.

Trans is already a future that does not exist yet, but returns to us to show the limits of the present. The politics of trans are also radically erasing the past and, in doing so, it is caught, as Hal Foster tells us about the avant-garde, in a constitutive and productive tension. On the one hand, the traditional avant-garde seems to turn more into the past, and for example, Isou’s film Traité de bave et d’éternité is already dead history. Like Isou’s film, the Romanian socialist realism is seen as dead art, and the link with the avant-garde is permanently buried, known only to a few specialists. At the same time, in its disappearing act into the past, it seems as if the avant-garde is returning from the future, especially in the innovative art of anarchist gestures that question gender as a social convention. Here, the avant-garde of the exhibition is different from a certain cynicism that has been installed in many aesthetic productions, where the radical gesture is only one of factional elitism, where issues are only for the niche to discuss, with the thought that “everything is the same” anyway. For queer feminist artists, hope is an affect they want, and they want it in relation to what they want to change. As the Soviet avant-garde was interested in how the new world can be directly felt, the stakes here are to produce an affect for the concrete realization of utopia.

Two things stuck with me: one is the direct act of self-exposure which, when performed in a safe installation, has the capacity to corrupt a viewer, to make them think about how they engage with the world. Here, healing is a direct political intervention as a way to change the other into what they feel is theirs: body, clothes, self-ownership. What Sasha Ichim does is tell us that only from a sovereign space of the installation, can change start as a political project. Otherwise, it’s just a permanent game on the opponent’s home ground, and the entire alternative left-wing loses mainly by playing on the very territory it denounces. The risk of exposure, when the dangers are anticipated, when they are carried out in the installation with the squad under conditions of solidarity, is super important, so to speak. In a world that is increasingly demanding the protection of private space and inciting people to shut down when they are invaded, a performance in which oneself is at risk is the key to understanding the possibility of corrupting the other one. Trans politics productively meets a utopian imagination in the gesture of risk and self-exposure.

The second invitation that I am responding to is witchcraft. Mystical maps generate other ways of knowing and, in doing so, they gesture to a different way of re-imagining healing. It can lead to work with trauma that we do not yet know how it can occur. Perhaps either the stitch or the tactile relationship with the trauma forms the basis of feeling more secure in your own body. But the maps should somehow be revised and reused more, because they could suggest another geography of pain and political possibilities. For example, in the witchy performance by Virginia Lupu I would have liked to see how the molten tin can articulate another map for the person partaking in it. Playing with the unforeseen may be one of the risks of guessing into the future, and the future may look completely different than the one already imagined. For Katja Eliad, as the curator told me, the game was to reconstruct the political and imagined whiteness of Romanians, which can cling to their hands when playing with the balls in the installation. A risk, but maybe in Kabbalah other gates could appear. The invitation is to open them in relation to a new political imaginary, and that is yet to be seen and felt.

If I were to draw a lesson from what I saw at Kunsthalle, it is that places and objects can be transformed and that trauma work is possible. But what I would have wanted more is to discover not only how healing is an act proposed by an avant-garde to me, but also how healing would be related to the history of the space and place where it is inserted. A relationship where the chosen place, Timișoara and its gentrified history, would be more visible and lead to a more direct political relationship with the friends and comrades in healing. Healing works, but locating the intervention in relation to the wound is its key.

[1] After all, what avant-gardist Isou did was to ask that his movie be screened at Cannes in 1951, although he was not officially accepted in the festival.

[2] With genderism I am referring to the attitude towards gender that separates bodies into female and male and essentializes certain given characteristics.

Comments are closed here.