The photographic image interposes itself twice between us and reality. It modifies both the bare gaze directed at reality, through which the eye that probes perspective senses distances, lingers over colors and shadows, gauges light, tests the consistency of matter, and the image we carry with us in memory, which photography then materializes on some support.

In the first case, as Vilém Flusser noted, between the gaze and the external world toward which it is directed stands the apparatus, a complex mechanism composed of lens, a surface for the world’s inscription, and a mechanism for the (re)construction of the image, with its own limitations and possibilities of seeing. Thus the photographic image expands our usual way of looking. Taking up Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s ideas, theorist Clive Scott identified a series of ways of seeing reality specific to the photographic language: abstract vision (photograms), exact vision (corresponding to reportage), rapid vision (snapshots), slow vision (variations in exposure time), intensified vision (microphotography, filters), penetrative vision (as in radiography or infrared), simultaneous vision (superimposition) and, finally, distorted vision (via various optical techniques). Next, we encounter the photographic image as a representation of the world when it is presented to us, whether on a digital support (on a smartphone screen or within the space of an art exhibition) as an image already produced by the apparatus and retouched by the action through which the photographer’s subjectivity at once reveals and constructs itself – or, more precisely, reveals itself at the very moment it is constituted, through the linguistic choices it makes.

In the case of the mnemonic image, akin to a freeze-frame projected onto the mind’s screen and co-produced with the help of imagination, affective intensities condense lived experience into an image-tableau. Within it, the contours of people and things often dissolve into a diffuse, milky mass around subjects that occupy the foreground. Photography takes on part of this mnemonic function, bringing into presence places, persons and situations that no longer exist, yet transforms it radically – conferring both precision (photographic images are for the most part sharp) and a fragmentary existence (being detached from the flow of lived experience and separated from the implicit meanings that such “snapshots” spontaneously acquire in relation to the broader situation or context from which the photographically fixed image is extracted).

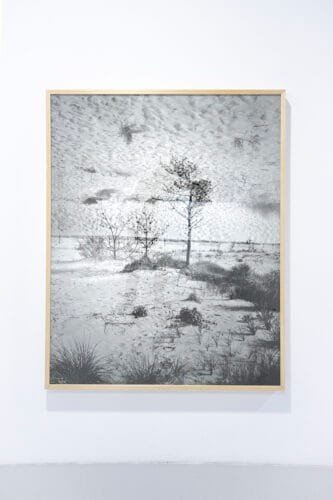

When we look at a photograph, then, we look at an image constructed twice – we encounter, in other words, a double performative production of the world. Each time, it proposes to us a specific way of looking and understanding. This is, in brief, also the very subject of the solo exhibition conceived by Claudia Retegan and curated by Matei Bejenaru at Borderline Art Space in Iași, which, on the surface, presents at the level of subject matter a series of exercises in contemplating landscapes that are more or less recognizable. The exhibition can be placed within the proximate genus of research-based shows that analytically explore the language of photography and for which the photographic image is not a simple imprint of the world, an image without a code (in the interpretive tradition proposed by Roland Barthes), but an elaborate reconstruction of lived (visual) experience and of how it relates to the world. Accordingly, the printed image is not presented as a window into the external world (akin to post-Renaissance painting) that offers itself transparently to vision like a pane of glass, but as a decomposed language, a rearticulated poem, employing a system of codes proper to photography (whose elements include color, drawing – lines and planes that compose forms –, depth of field, exposure time, as well as the manipulation of multiple images through montage).

Thematically speaking, although their apparent subject is nature, Claudia Retegan’s works inscribe themselves in the wake of conceptual photography, inadvertently laying bare an education undertaken in New York and Los Angeles. They thematize the condition of analog photography in general and of landscape photography in particular, decomposing and reconfiguring the photographic language and its various materialities like a lesson in the grammar of photographic looking (a preoccupation the artist shares with the photographer Matei Bejenaru, here in the role of curator). Yet the exhibition in Iași succeeds in translating these usually arid, purely intellectual concerns into a disconcerting experience. Perhaps surprisingly, the interest both artists show in the self-reflexive thematization of the photographic medium does not lead to a didactic, sterile display. On the contrary, following Byung-Chul Han (and Nietzsche), Retegan is interested in exploring the limits of signification, both verbal and imagistic, in exposing the intrinsic violence of imposing a stable meaning, and in probing the manner in which cognitive, interpretive experience gives sense to the visible world by imposing significations, codifying spaces and projecting meanings where these are felt only affectively and usually develop through the collaboration of several senses.

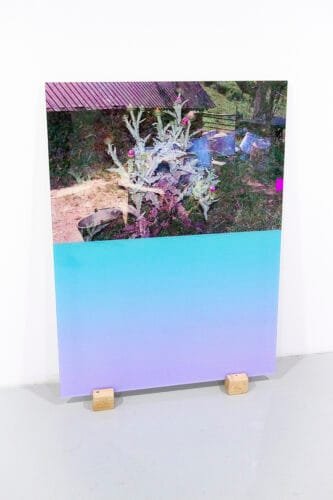

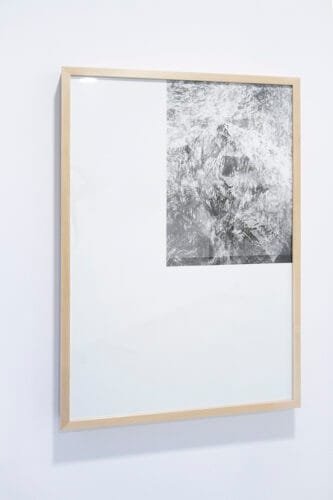

This phenomenological experience, determined to a large extent by the carefully orchestrated composition of the exhibition space (in which the artist expands the photographic frame beyond the limits of its mount), as well as by the sculptural approach to the photographic object, carefully produced and framed – using Diasec or thick natural-wood frames and silver-gelatin printing from analog film – constitutes, in my view, one of the most striking qualities of this artistic undertaking. The artist’s decision to extend the image frame by means of graphic gestures – which can be read as extensions of chromatic elements or of lines found in the images’ composition – happily becomes a decision that amplifies the image’s somatic effect. Consequently, it recovers part of the sensory impact of the encounter with an image that is phenomenologically salient, capable of lingering on the retina, once again moving beyond the oculocentric reductionism dominant in Western philosophy, as Martin Jay noted already in the 1990s, following the French post-structuralist philosophers. According to this reading, the history of artistic representation can be understood as a long sequence of attempts to temper, control and master reality. For Jacques Lacan, for example, artistic representation serves to domesticate the Real, to make it intelligible and bearable, and in Martin Jay’s account, oculocentrism entails reducing the image’s frame to a single view – derived from the picturesque veduta genre, an exemplary image of a place that becomes a souvenir, an aid to memory – which, we might add, is nothing other than a consequence of anthropocentric epistemology.

In the photographic universe Claudia Retegan proposes in this exhibition, images produced by superimposing two or more frames, as well as by a visible intervention on the frame – cropped, made explicit and transformed into a compositional element – do not allow themselves to be controlled by the spectator’s gaze. On the contrary, they unsettle and disconcert, shifting the viewer from the privileged role of judge of an image or passive receiver who is nevertheless singled out and targeted, whose attention is solicited at any cost in a capitalist economy of intensified entertainment. In these series, Retegan initiates a broad endeavor to deconstruct the traditional notions of the photographic “snapshot”, “postcard”, and “landscape”, while also deconstructing the photographic frame and emphasizing the construction of reality through specific photographic techniques such as spatial montage, using flash in daylight (which turns foreground objects into photograms, quasi-abstract forms), cropping (and the simultaneous use of the resulting negative space) or extending the photographic frame (by means of vinyl markings added to the wall so as to make each image a photographic installation resulting from the spatialization of photography). At the same time, her photography approaches painting in several ways: not only does it assume a subject traditionally reserved for painting (the picturesque), it also employs painterly abstraction translated into photographic elements in the form of blocks of solid color with simple geometric shapes that condense chromatic elements existing in the photographed frames (and which, from the standpoint of photography, recall the practice of color sampling used in calibrating print or monitors).

Indeed, a deconstructive concern can be discerned in her artistic practice that can be extended across several planes. First, the images produced are traces, though not exact imprints of reality. The production of a single image through the superimposition of two different frames (different modes of perceiving the same subject or different images of similar spaces) decisively distances the constructed image from that indexical quality celebrated by Roland Barthes. Yet, as traces of a subjective experience capable of triggering the process of remembrance, they not only bring back into presence “what once stood before the eyes” that look through the camera lens (as Barthes would have it), but also betray, at the same time, a constitutive absence in each frame. And the most salient absence felt in these seemingly coherent images of ordinary natural spaces, in which human presence is completely absent, is that of the author’s body. She remains, then, a diffuse presence, invoked not only through her actual absence from within the frame as in selfie photography (yet perceptible behind the camera as a gaze that selects, pans, zooms, etc.), but also through other artifices such as the discreet use of actual bodily elements (for instance, a hand entering a frame). Secondly, Claudia Retegan’s pronounced and recurring interest in the parergon, in what can be seen within the photographic frame and what photography leaves aside, occludes, blocks from view or omits from the field of the visible, as well as the constant relation between the frame’s interiority and exteriority – which often becomes a compositional motif through its use as negative space – both evokes and deploys the vocabulary of Derridean philosophical deconstruction. Moreover, a broader series of binary oppositions is undermined here, such as interior/exterior, surface/depth, figure/ground, painting/photography, snapshot/staged photograph. Not least, considered solely from the perspective of the photographic language, the exhibition can present itself as a staging of writing – an equating of all forms of inscription of a textual, gestural or imagistic communication with the aim of being remembered and which, precisely in this process, becomes opaque and occludes immediate access to the primordial meaning of the experience that seeks to be communicated.

It is also noteworthy that, in recent decades, art photography has increasingly borrowed the status of the pictorial or sculptural object, limited and precious, most often printed, materialized at whatever size its author chooses, and protected by a casing (frame, glass or plexiglas) which indicates to us what we can see and how we are to look at what it wishes to present. It greets us, therefore, at a somatic level, like a dialogue partner. The photographic image often becomes an image-object endowed with agency in the tradition of materialist philosophy, with its own capacity to perturb (rather than an inert, passive object), and at the same time a living image that comes alive affectively. As an extension of artistic subjectivity, the photographic object most often displayed today in the white cube of the art gallery or museum greets you, then, like a host who engages you in a conversation: it decides not only what we ought or ought not to speak about, but also what you can or cannot disclose, as well as the tone of the conversation that is about to take shape – intimate or formal, imperative or constative (in the case of socially engaged or expressly documentary photography), which either incites to action, or asks you to act, or, on the contrary, is exclamatory. In all these cases, art photography represents the perfect occasion for constituting a situation of aesthetic encounter, as defined by Baptiste Morizot and Esthelle Zhong Mengual. Understood in terms of an “aesthetics of encounter”, the work (that is, the political, ethical and ontological effect) of art consists in configuring a meeting with a foreign form of life. And the exhibition becomes a space in which aesthetic communication entails recognizing alterity on its own terms, training our capacity to observe and acknowledge the details, differences and recurrences implicit in the act of perceiving.

Understood in these terms, Claudia Retegan’s photographic project decomposes the transparent frame of indexical photography and compresses different points of view not merely as a postmodernist exercise immanent to an artworld of its own that would act exclusively upon the history of photography, but also with a precise ethical and ontological commitment. It decenters the viewer, challenges perceptual habits and, at the same time, reconfigures the relationship between natural space and the human gaze, underscoring the eminently relational character of this rapport. Thus, Retegan’s elaborated interest in representing nature becomes, implicitly, an exercise in re-examining the relations between viewer and the natural world and, in a broader sense, an ethical exercise of repositioning oneself in relation to nature within a post-anthropocentric universe. Hence the answer to the question in the exhibition’s subtitle (“And, by the way, who still makes landscape photographs today?”) can be found by examining what landscape has become for us in an artificial universe in which nature no longer represents a foreign object, or an estranged familiarity exposed to scopic examination and human control, but becomes a partner in a long-term relationship. If we understand both nature (which refuses to be turned into landscape) and the artistic image (which refuses the status of a docile, transparent representation of nature) in this way, we can conclude, together with Morizot and Mengual, that this exhibition situates itself within a broader crisis of contemporary sensibility: “an impoverishment of what we can feel, grasp and weave in terms of relations with the living. A reduction of the range of affects, of percepts and concepts, as well as of the practices that bind us to it.”

By multiplying and expanding the usual ways of looking at, contemplating and examining nature, the photographic and exhibition project proposed by Claudia Retegan lays bare this double crisis (of photographic representation as an image dependent on the photographic apparatus and of the scopic relation to nature as the world of the living) and offers compensatory formulas capable of enriching the way we pay attention to the world.

Claudia Retegan

“A Sunset Less Than Perfect. And by the way, who still makes landscape photography today?”

Borderline Art Space, Iași

22 May – 2 July 2025.

Translated by Dragoș Dogioiu

POSTED BY

Cristian Nae

Cristian Nae lectures in history and theory of art and the Arts University in Iași. He works between visual studies, aesthetics, exhibition studies and geohistory of art....

Comments are closed here.