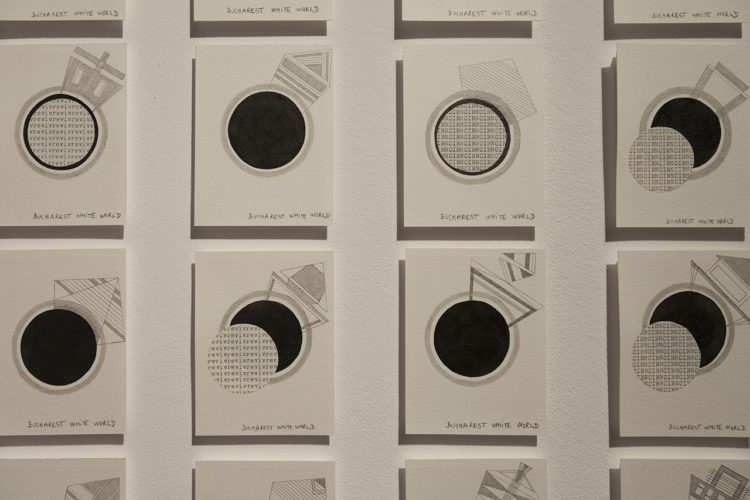

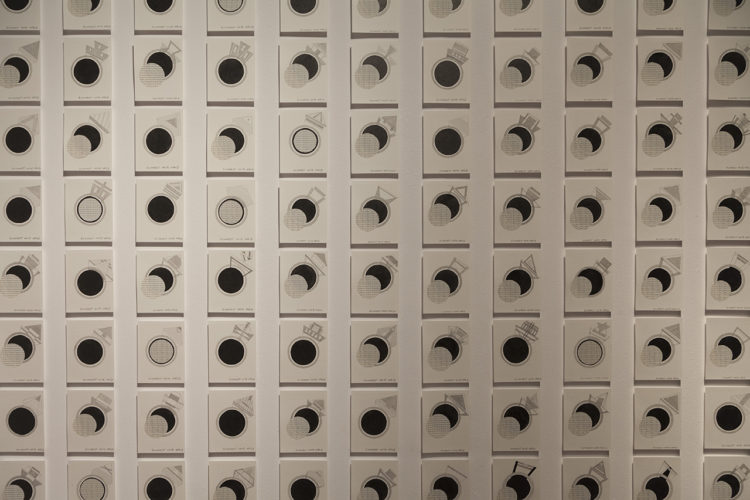

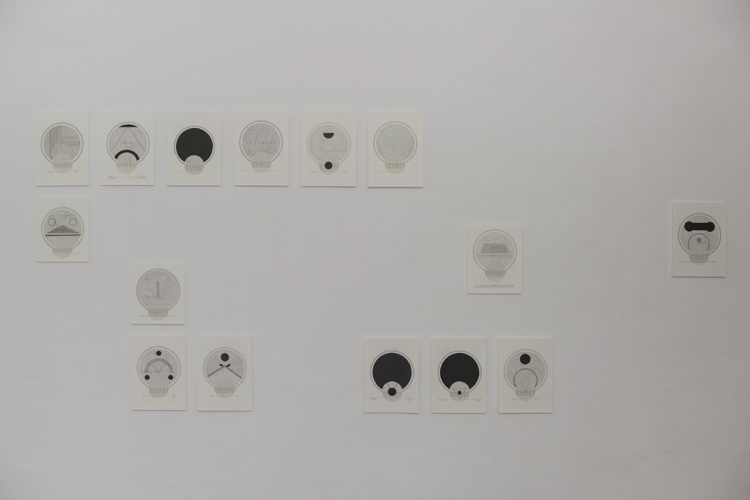

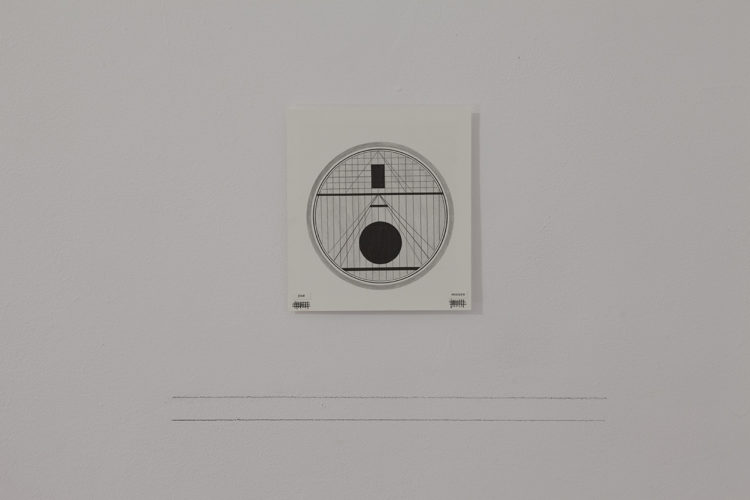

At the entrance, a room with wooden floors and a wall are blocking the back side of the room. On it, a matrix of 13 x 13 geometrical designs, some black circles, with or without text in them. A cryptic exhibition at a first glance. I approach the wall and I can’t understand a thing. Inside a circle, vivre vivre vivre vivre… is written obsessively.

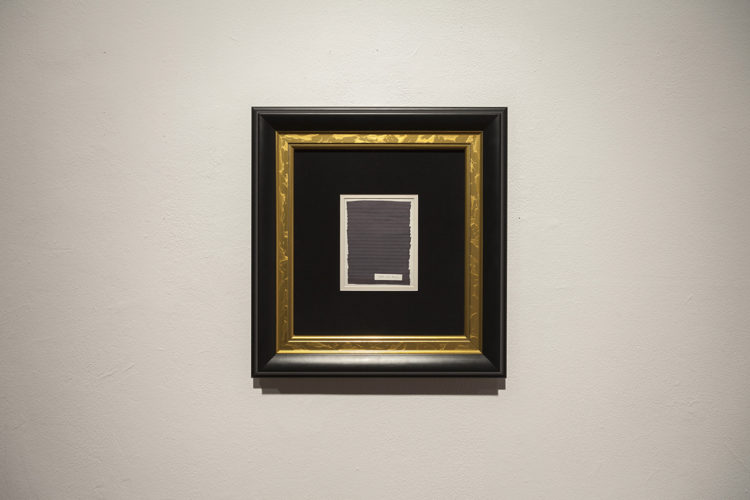

I turn to the left. A framed sketch, with horizontal rows of black hatching that forms a square that covers almost the entire surface of the sketch. In the lower right corner you can read the boat is full. A big black frame surrounds the sketch. Followed by a wide band of black velvet.

I am starting to wonder whether the matrix is actually an arc.

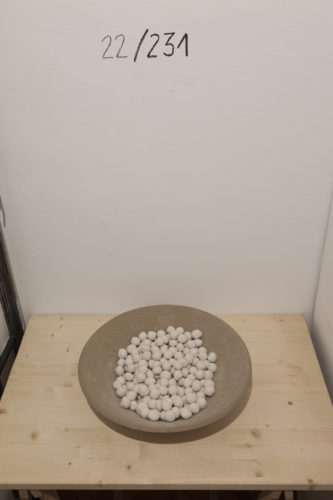

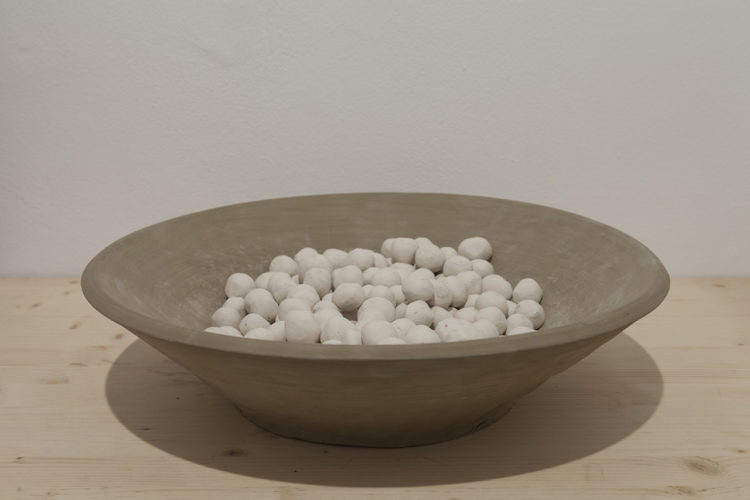

The matrix wall is hiding a narrow room. At the end of it, a table. On the table, a big clay plate with some pieces of ceramics in it. If you touch them you get white dust all over your hands. Although the object is attractive, I still feel left outside of the loop.

I read what is written on the wall without understanding.

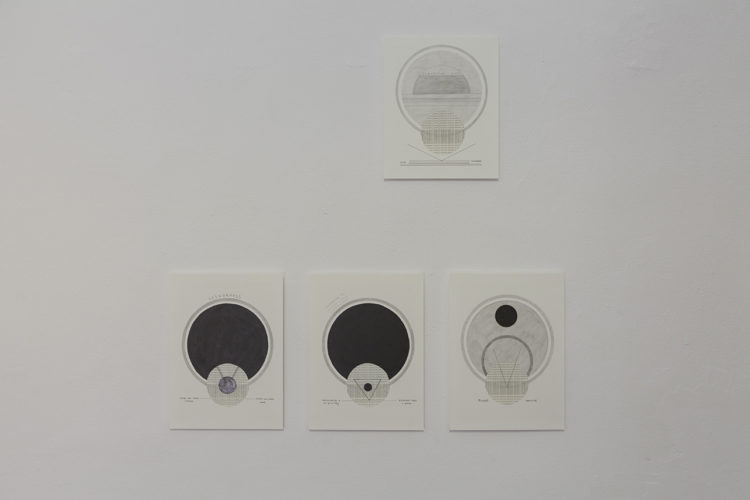

I step into a third room and the atmosphere changes. If the other rooms had a funerary way about them, it seems as here we are beyond death, beyond the grave. The black sun of the matrix has escaped the shadows. A bronze gryphon is now a decorative support for the small white bulb left lit on the floor. Demons no longer consumer the sun, which is now shining as a big luminous globe set on a decorative rug.

Without realizing, I’m thinking that at least there is light and love on the other side. I am somewhat glad to be rid of the stuffy and oppressive atmosphere. But I begin to gaze at the drawings on the wall and I realize it’s not over yet. Every sketch seems to be an extremely tensed story. Next to a group of three drawings, on the wall is written – she jumped from the balcony – as if there was no more room on paper for this outcome.

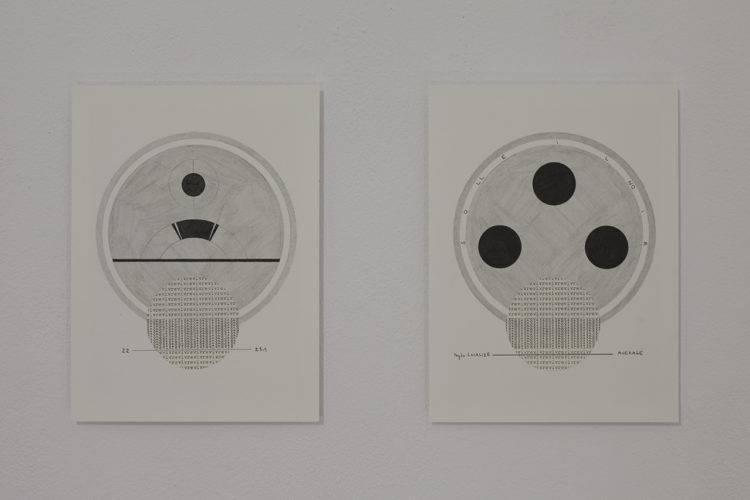

The matrix with small sketches from the other room was almost mute. It was uttering just 2 words – vivre and noir. Both repeated over and over, like typography exercises, like types of wallpapers with text or some obsessive, feverish, hermetic rumination.

But the sketches of this room speak more articulately, even though via a fractured language. There is a drama here that I take part in from a distance because it seems a little bit too forced. The problem is, as I read on, I understand that we’re dealing with an issue of pronunciation, linked to those things which make up life and overwhelm you with their visibility but also the pain they cause. It is the reflex of someone who wants to talk but has a hard time and can’t find their words because emotions get the best of them and makes them keep quiet.

Or better yet, I suppose it’s keeps her quiet.

What passes this barrage of painful emotions are significant pieces. They seem like childish word play or some attempts at verbal formation during psychoanalytical sessions.

The wrong words often tell the truth in funny, though not too cheerful ways. Cosmo – polite / jonglé – identité / pathological – y for today /exile – la question dort – encombre.

Here, the sketch becomes an easy to read cipher, even for an unsuspecting visitor. And so, the exhibition slowly begins to unravel its meanings and contents.

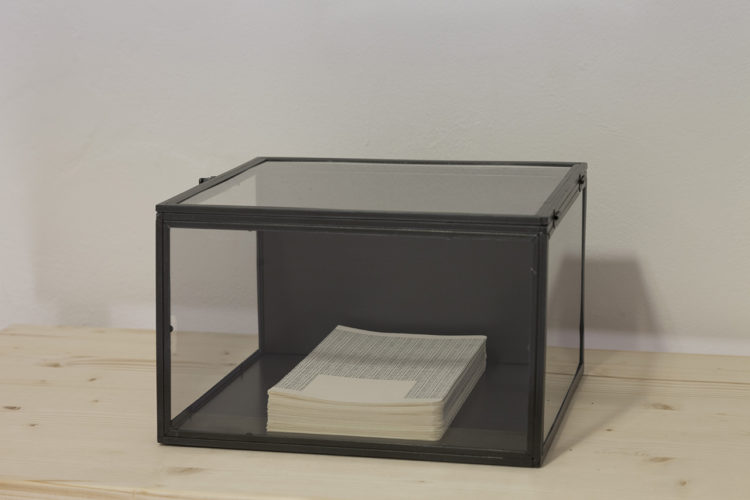

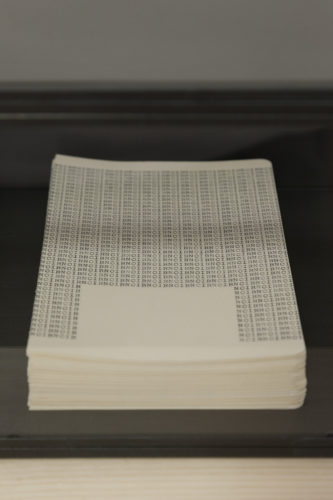

And the last object in this room. A transparent case with a metal structure and a removable lid which contains a stack of papers with the word noir, again, written obsessively, but in the shape of a gate. So the lower part of the repetitive text is interrupted and the rectangular for of the text has an opening. All placed under a drawing of a red circle, the only colored element in the entire exhibition, a place which appears to be marking something special, like an altar

The show makes use of obsessive writing in order to place the affect horizon of the trauma to the level of such an ancient suffering, it reaches the limits of consciousness and language. It cannot be fully named, nor it can be correctly delimited or comprehended by consciousness. Behind the depths of adult thinking lie senile and depressing old age, or confused and still unassuming childhood. Along with the entire history of our species, all its crimes and frights. But also the divine in man, gathered as if it were a bunch of interior forces. That is where Katja Lee Eliade goes in order to speak of what is happening.

And she speaks cryptically, she speaks like a child, she speak poetically, neurotically and obsessively. But when all is said and done, she can clearly and comprehensibly utter the name of this world, but also the name of the other world.

Perhaps this is why her sketches remind me of how surrealists used text. Somewhere between magic, neurosis and pure poetry. Visually, Malevici’s suprematism seems to be an important source.

The geometrical forms also have a symbolic side to them, linked to Kabbalah, also confirmed in the curatorial text. So do the numbers on the wall. 231 gates open towards the infinity through the mix of combining the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet, we are told. The text also reveals the meaning of the ceramic elements in the middle room. It’s about Romanian land molded by master potters in the shape of stones. On Jewish grave, people place a stone to mark the visit to that specific tomb.

The exhibition was solemn. It’s most important success is being able to articulate, by means of contemporary art, a structure for the cosmos that is completely alien to contemporary man. It’s about that cosmos made out of this world and the other world. Due to the funerary nature of the first two rooms, it appears that this is the land of the dead and that the other world is, in fact, a place one could live in.

When seen through the lens of minorities’ historical suffering, her own heritage, this type of positioning and construction are completely motivated. Still, at a religious level, because the art show has a statement of this sort, reducing the world exclusively to black and the imperative of an unhappy life, seems an Manichaeism almost too hard to accept.

Another observation that came to mind as I was visiting the show was linked to its title.

Bucharest White World ought to be a kind of brutal, direct statement on Romanian racism, where Romanians, in the most general sense, totally identify with Aryans and the associated Nazi ideology. I don’t doubt that this is all justified.

Problem is, today, just like yesterday, the nationalist discourse wants to make everyone forget that, best case scenario, as Ovidiu Ținchideleanu put it, Romanians can pass as white at best. In this sense, neither the majority of Romanian ethnics nor the national minorities are white. Especially to the west, where we’re all seen as eastern-Europeans, so in no way equal to westerners and certainly not at a racial level. Perhaps this is the state that actually needs to be corrected with dignity and self acceptance but historically, it has been and is corrected with violence.

By claiming a type of superiority by some group and a type of inferiority by others.

Yet, when speaking of the collective history of the community she is a part of, Katja Lee Eliad still adopted a somewhat dogmatic discourse. To be more clear, being preoccupied with the Jewish drama during World War II, Holocaust studies have created a public discourse that shows very little interest for solidarity with other historical victims of the Nazis, like the Roma or the LGBT community.

Although the Roma holocaust has its own extensive chapter in the Final Report of the Elie Wiesel Commission, thus becoming a very discussed issue in the academic circles, this part of local history did not find a visible place in the public discussion around the Holocaust or in the local artistic consciousness. As for the LGBT community and the Holocaust, in this case not even local academic studies did not reach too far due to Romanian legislation which states that the files in the case of the morality trials will never be declassified.

This is also visible in Radu Jude’s film, where all of these histories are completely absent, perhaps as a reflex of the hegemony brought on by the very same discourse.

And it is in this point where a new historical and affective horizon could open and actualize a simple realization: there are other groups that have suffered throughout history and it is important to open up to their histories. They can help us escape the marked horizon of our own ethnicity and its perhaps singular destiny.

I think these are some places where Katja Lee Eliad’s work becomes fragile.

Beyond that, I can say with certainty that just like Mihail Sebastian or Paul Celan around World War II, or Ștefan Sava, Belu-Simion Făinaru or Olga Ștefan, closer to present day, Katja Lee Eliad is part of a long list of Romanian intellectuals, regardless of ethnicity, preoccupied by things no one wants to talk about.

The ’40s in Romania meant pogroms, Holocaust and world war. The ’50s and 60s meant gulags and the political repression of all social classes. The wealthy bourgeois, the petty bourgeoisie and the peasants. The ’80s meant starvation and isolation, the ’90s meant fear, the disruption of the industry, financial booms and extreme poverty. And the 2000s also meant total poverty for 40% of the population. And the biggest emigration rate after Syria, a country ravaged by war.

These are some of the few burdens we have to face as a nation. They also hold the reasons why we are so disunited. The reasons why we hate each other so much. Be it racial hate or class hate, it almost doesn’t even matter anymore.

And it is this mine field where artists come and work with the local collective memory. And t is an act of courage to show your wounds to others, so you can heal.

Katja Lee Eliad, Bucharest White World, curated by Valentina Iancu, was at Galeria Posibilă in November 2017. On the 12th of January, Perform, the follow-up to this project, opened at Calina Gallery in Timișoara.

POSTED BY

Ionuț Cioană

In 2006 Ionuț Cioană started to work as a visual artist, developing a series of projects under the alias Mircea Nicolae....

Comments are closed here.