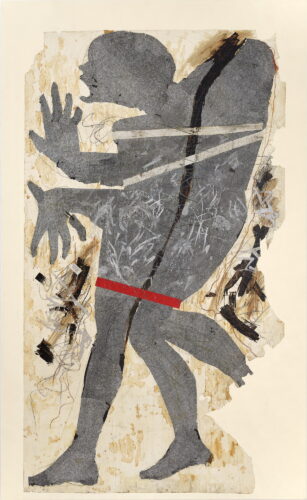

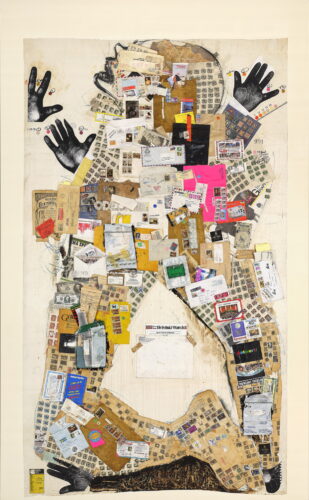

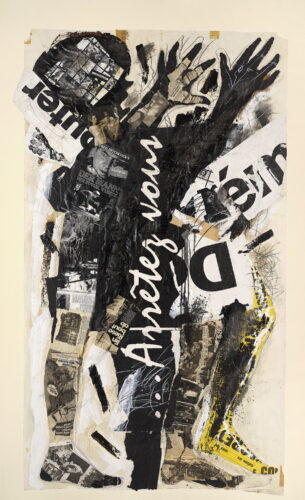

Whoever visited Gaep this summer encountered Mircea Stănescu’s giants and most likely gazed at them in wonder. From a distance, they are human figures that look unwell. They seem tormented by fears and depressions, by pain and anger which make no noise, but which grind and overwhelm. They are mirror-figures of inner turmoil and suffocated aspirations, hunchbacked, stooped characters, cramped in their own body. Once the eye, upon getting closer, meets their stomach and begins to travel up and down, as if scanning an X-ray, you begin to see the kind of tiny things that can nourish and delight a person’s mind: French phrases, movie posters, magazine clippings, clothing patterns, postcards from foreign countries, envelopes you want to open. There is a nature giant, teeming with dried flowers and pressed leaves, and a mail art giant, like a postman who scattered his bag, a cinematic giant and a touristy one. They may seem scary for a second, then you realize they might be your kind of people. They all carry a dose of nostalgia and they are all eager to explore. They are all serious and they are all playful. The curiosity and freshness they exude make them ageless, restless in all possible ways.

These collages are „an aesthetic alternative to communist isolation and the frozen time in which they were conceived,” as Liviana Dan describes them in the exhibition text of Meditation upon Measure. The body, the curator says, was the frame most at hand for Romanian artists in the 1980s. Using its generous structure, the layers of a utopian biography were easy to lay out.

Restored and exhibited on Gaep’s both floors, along with other mixed-technique works by Stănescu dating from 1986-1989, but also from the past two years, the giants are over 2.5 m tall. What makes them even more imposing is the realization that they reached us, despite their difficult history and the fragility of everything they are made up from, with their entrails intact. The giants don’t only tell the story of their author, but also the story of the years before the fall of communism, when they were made, and the years they travelled through; looking at them, you can’t help but think that without a project of recovery and conservation, they may have never had their moment in the limelight, they may have eventually yielded under their many burdens.

The Gallery

Gaep’s co-founder Andrei Breahnă remembers meeting Mircea Stănescu in 2015, and discovering, on that occasion, a private person, “a discreet man, of extreme refinement” who “did not show much of his work to anyone.” It took him a while to get to see some drawings and he immediately realized that he wanted a long-term collaboration with the artist.

He started by organizing an exhibition at the then called Eastwards Prospectus gallery. Abstract Matters opened in the fall of 2015, focusing on black-and-white photographs of New York after 2010. Divided into three rooms, each one with its own theme (Fire Escape Ladder, Under the Hoboken Railways and Pier), the works revealed different degrees of clarities, shadows and geometries, a fragmented and intense way of seeing and rendering the elements of a foreign city.

As the relationship between gallerist and artist deepened, Breahnă found out that Stănescu, born in 1954, was keeping many of his works from the 1980s and the 1990s in a chapel attached to a school in Gușterița, a suburb of Sibiu. They were taken there, after a brief stop at the Brukenthal Museum, for lack of a more generous storage space. In this unsuitable place for art storage there were different-sized collages, drawings, photographs, as well as numerous exhibition catalogues, magazines and objects. “It felt like an archeological mission,” Breahnă says. “Together with a colleague, I made several trips there and, on sunny days, we were taking the works out in the school yard and looking at each element, finding that certain works were compromised, while others were salvageable. A few months later, we were able to bring the entire set of works and objects to the gallery.” A small research and archiving project led to a table containing 800 elements, photographed and filed. Having done that, together with Mircea Stănescu and with the help of curators Liviana Dan and Tevž Logar, the gallery first selected 40-50 works, most of them large-scale collages, from which to get started on what would eventually become the Meditation upon Measure exhibition.

The need to restore most of the works made in the 1980s arose from the very beginning, and the task was eventually entrusted to Cristina Petcu, conservator of graphic art. She did not only contribute to a reconditioning of the works and their preparation to be exhibited for the first time in this form, but was also a factor in a rebirth of sorts, a process made possible by a permanent consultation with the artist. Meditation upon Measure manages to embrace more than three decades, causing the awakening of works from a long and forced hibernation and, at the same time, capturing the evolution of an artistic practice and vision by bringing the old into dialogue with the very recent.

The Curator

The context matters, although it is hard to encompass.

“This is the first problem of the ’80s generation. It is not contextualized,” says Liviana Dan. “In a way, in those times, we lived alongside things. We were very involved, critically, socially and politically, but much rather in the ideas of a place than in the place where we activated. It was a bizarre matter. In a way we were very involved and in another way we were excluded, because nobody paid attention to us.”

The 1960s, after Nicolae Ceaușescu took power, brought an apparent relaxation and improvement of life, a cultural liberalization and a certain openness to the West. The 1970s offered artists, otherwise strongly thematically restricted, the levers to show their work, to participate in biennials and, in general, to develop their practice. It was the regime’s way of proving, at home and abroad, that our country could do it, too. “Then, in the ’80s, everything got stuck.” Liviana Dan hardly goes back to those times, not because she doesn’t remember vividly every millimeter of discomfort and closure, but because she feels that the re-activation of memories hurts her physically. That’s why she has avoided for years to reopen the notebooks in which she kept a daily diary. That’s why she feels that whatever she and Stănescu, who is also her life partner, tell about that decade is impregnated with something they failed to shake off even after 30 years, something they and the people in their entourage share, and yet which differs greatly from person to person. “Everything you say gets a dramatic tone. We still can’t find a normal tone.”

That world from well behind is a world where they were young, but did not have access to books, music or any kind of instruments needed in order to feel they could build towards or aspire to something. The radio everyone listened to and nobody talked about was Free Europe. They were living in a samizdat, where books were copied by hand and passed from hand to hand in intellectual circles. Any meeting places and gatherings of cultural figures were firmly supervised. Having no ateliers, artists worked where they could, and this often meant small rooms for large and countless ideas; if they were lucky enough to be put into practice, many works did not fit on the door, had no place to be store in, or showed to the public. When artists exhibited, they did so mostly in basements, in tiny, marginal and obscure spaces. “Everything was done in a clandestine and underground way, and that seemed conspiratorial and attracted even more hostility or attention from those who were scared of what could be,” says Liviana Dan.

In her book Artele plastice în România: 1945-1989. Cu o addenda 1990-2010 (Polirom Publishing House), art critic Magda Cârneci writes about a much more aggressive social and professional marginalization than that experienced by previous generations, which forces young artists who have “neither the privilege of hope (as in the ‘60s), nor the advantage of the remaining illusion (as in the ‘70s)” to organize themselves in small groups and to resort, to a large extent, to isolation. “In a blocked social situation, without a credible mental outlet towards a forward (now discredited) or a backward (forbidden, impossible), in some sort of stasis of the social field and of the collective psyche, the young generation of artists and critics reorients itself – inevitably – towards interiority and individualism, towards other values and functions of the creative act.”

In this gray area, Atelierul 35, which first appeared in Bucharest and was then developed on a national level, allowed young artists to look for and find each other in a more relaxed environment, circulated by un-resigned energies. “The existence of Atelier 35 was essential for the core of the art and spirit of the ’80s generation during its period of rise and affirmation”, writes Adrian Guță in a 2012 issue of Revista ARTA. “I am referring, of course, to a substructure of the Union of Visual Artists, also controlled by censorship, but it was, in the last decade of the communist regime, the most dynamic and undisciplined formation of the artistic guild.”

One of the key events held under the emblem of Atelier 35, the Colloquium of Criticism and Young Art organized by Ana Lupaș and Liviana Dan in Sibiu in 1986, allowed the unrecognized generation not only to show what it worked on, but also to meet and exchange impressions of what it meant to be an artist in those days, while also getting acquainted with everything they were curious about, from Beuys and postmodernism to critical institutional programs.

Also particularly significant as a manifestation of the times was mail art, which now seems like a paper plane that managed to enter through a window which was slightly ajar. In the envelopes with foreign stamps traveled works from worlds with which there was no other form of communication, and which allowed a minimal connection to the external vibe.

The Artist

This is the kind of world Mircea Stănescu made his way towards in the late 1970s. “You had to know how to choose,” he says of the life of a young college graduate during communism, “which was a problem, because you didn’t have much to choose from.” He had graduated from the University of Arts in Bucharest, in the Tapestry department. To the obvious option of teaching intensely politicized art to even younger minds he preferred the one to get hired in the industrial sector. That is how he ended up working at the carpet factory in Cisnădie, where tens of thousands of square meters of carpets for export and protocol houses were made every month. The complex system that allowed the reading of punched cards for the production of carpets seemed symptomatic to him for the times to come, times of signs and predisposition to numbers and coding.

While at the factory everything was colossal in size, his art made its way into the world on short walls, cramped by space. At one time, he had a studio in a 2/3 m room, on the 4th floor, close to an exit from Sibiu. There was no elevator, only stairs he could not descend with a canvas larger than 2 meters. He had chosen collage as a means of expression, because it “indicated an instinctive dissatisfaction, a reflection of a failed existentialism, with empty drawers, which bore the convulsive stigma of red propaganda.” For him, the collage was an adventure between physical dimensions and mental projections, from 2D to 4D. “The ineffable of the collage dominated the border with the unreal, between a deaf and absurd existentialism.”

Materiality was a strength of the 1980s generation, and in Stănescu’s case, says Liviana Dan, it was even more significant, because he had had an education and had gained work experience in a field of textiles and weaving. “For him, materiality was both a support and a medium.”

Stănescu remembers about a day when, returning to his flat, he found that he could not open the door. “I jumped from a balcony to get into my own house. I disassembled the lock, and saw that someone had inserted a screwdriver in it. Someone told us: Worry not about them stealing something from you, but of them placing something inside.” Had anyone searched, they would have probably found some of the hundreds of small items that came to form the entrails of Stănescu’s friendly giants, exhibited this summer at Gaep: strings, corks, magazine clippings, candy packaging, postcards, posters, leaflets, invitations, flowers, leaves – the relics of a compulsive accumulation and the only things you could cling to to build your forbidden self.

“You needed materiality to give yourself the impression that you possessed something,” says Liviana Dan. “Any piece of string that was slightly different, plastic bags from abroad, magazine clippings …”

“The symbols of a world that existed only in your dream”, adds Stănescu.

The Work

Meditation upon Measure requires through its large-scale collages and mixed-media works on paper or fabric a permanent adjustment of gaze and interpretation, between the concrete that almost seems made to be touched and the abstract that distances itself through white space.

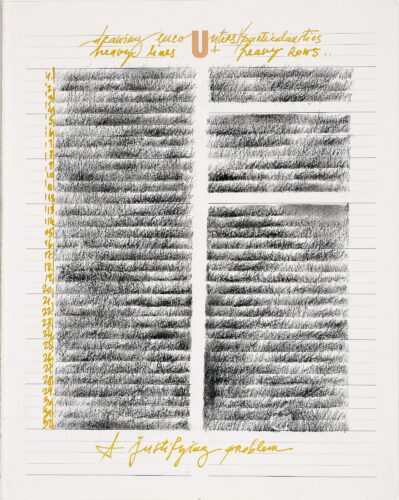

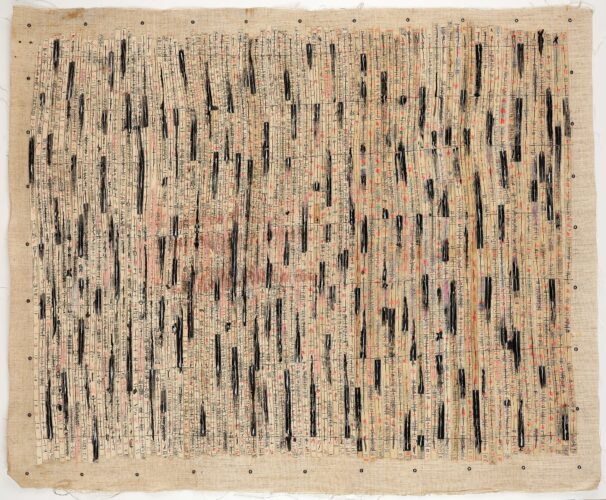

From the very first room, Stănescu’s preoccupation with time, an important theme in his practice, becomes obvious. In small frames, several agenda pages literally shine, vibrating between the lost time and le temps retrouvé. Their time, pigmented by the contemporary materials that the artist now has at hand to express himself, is completely different from the one in the surrounding couple of works, a time of the 1980s that Liviana Dan describes as very strange: “We lived from day to day and from moment to moment. On one hand, time was very open and, on the other, it was very limited, because you were being watched.” These two works from 1986, textile collages for which the exhibition is named, are made up of dozens of narrow strips that Stănescu gathered while working at Cisnădie. The strips –yellowed by time, glued and sewn next to each other, seeming to flow together, but also separately, like an impenetrable cipher – contain numbers according to which the cards used by the jacquard device were being punched. Suspended on the walls of the gallery, and placed in the light they had been craving after for decades, the works impose a kind of deference, as if they held a personal mythology that they flutter without disclosing.

In another room, drawings from the late 1980s scream hidden despairs from all their shades of pink, their numbered seals and charcoal lines. But nowhere does the idea of forceful artistic gesture make more sense than upon seeing the giants downstairs. The collages were mounted (Stănescu uses the term “marouflage”) on canvas that had been stretched on wooden chassis, a solution that gives them stability as well as resistance. In a way, the project allowed the artist to revisit something he once did and, at the same time, to see it for the first time in the form he intended for it.

Several smaller works from 2020-21, included in the exhibition, form a bridge between the Mircea Stănescu of back then and the one of nowadays, who fully enjoys the freedom to say what he wants to say, using the exact tools he wants to say it with. Whether it’s the drawing of a piece of string, interventions with silver glittering powder on agenda pages or works for which he used golden ink, Hahnemühle or Fabriano paper, these new pieces seem almost eccentric manifestations. “Now there is an indulgence in accumulation”, says Liviana Dan. ”You can have style and decide what you accumulate.”

Meditation upon Measure is on view at Gaep through July 31.

POSTED BY

Gabriela Pițurlea

Gabriela Pițurlea is a freelance writer and editor. She studied Journalism and Advertising, and started by working as a reporter for Esquire Romania and DoR. She is the co-founder of SUB25.ro....

Comments are closed here.