Platforma was almost a mythical place for contemporary art in Bucharest, active between 2011 and 2015 in the building known as the MNAC Annex. It was a place of encouragement for young artists’ projects that were generally produced with no money but a lot of enthusiasm. When the museum closed down the space, the artists that activated the space with their performances formed the Local Goddesses, and they’ve been coordinating the Multimedia Gallery of the UAP, CAV – Visual Art Center since 2016. I talked to 4 of them, Simona Dumitriu, Ileana Faur, Ramona Dima and Claudia cea Minunată about their artistic and curatorial route.

How did Platforma begin? Who initiated it?

Simona: I think the idea was in the air the moment the privileged circles of the art world started to learn that MNAC [The National Museum of Contemporary Art] left TNB [The National Theatre] and moved on Calea Moșilor 62-68, in a building that was hastily renovated (cleaned) and where a part of the collection and offices relocated. By 2010-2011 rumors were that some of the floors could be used for organizing art shows. There was a graduation exhibition I think (in the year Lea Rasovszky graduated) for the Photo-Video department, End of Academia in 2010 – that was the public’s first contact with the space and its industrial feel. After that I spoke to Lea, then I got Bogdan Bordeianu and Simona Vilău involved; we started meeting and thinking about the possibility of asking Mr. Oroveanu [the museum director at the time] for one of the building’s floors. At that moment it wasn’t clear what was going to happen with the space, I heard they wanted to make a photography museum, it didn’t have a clear name either – the generic name “Photo Annex” started flying around, which later turned out to be the name of the 3rd floor, while the building started wearing a sign that said “MNAC Annex”. These meetings gave birth to a program and we solicited the support and recommendation of Mr. Iosif Kiraly [tutor at the arts academy, UNArte] – who I was close to during that time when I was also teaching at UNArte. With his help we put forward for Mr. Oroveanu a year long program that he accepted and that’s how we started out.

That first year program was kind of a hybrid, everyone put forward their own interests: Lea and Simona had freestanding curatorial ideas, then there was the close connection with the Photo-Video department.

Did you jointly decide what exhibition would take place? Did you talk about a common, coherent vision?

Simona: I wouldn’t say a common vision, everyone had a different idea regarding the space. Over the years, our program was not at all unitary because it took shape depending on who had the availability to do certain things. Over time we started working towards a common vision of social and later feminist organizing, then the group got narrowed down and then, towards the end, a program was coagulated.

The team changed a lot over time too. Before Bogdan took off, Marian Dumitru, who was still a student, showed up after he first came into contact with Platforma as part of the project Second life in communism. Then Ștefan Bandalac, Ileana Faur showed up, then later Claudiu Cobilanschi and Alexandra Șoldănescu for a short while.

Ileana: I remember that an add popped up on the school’s online group that Platforma was looking for volunteers. That’s how I got there.

Did you ever receive funding from the museum for Platforma?

Simona: Not for Platforma, but rather for actual projects where we needed to produce prints and couldn’t afford it: a project by Mircea Nicolae with Michele Bressan, another one by Sage and that’s about it.

The museum gave us the space for free, we didn’t pay the bills, we had a gallery keeper that took care of the place.

Did you work based of proposals, on open calls?

Simona: They were project-based calls. The first was in 2012 when we applied for AFCN funds with the help of Galeria Nouă Association, coordinated by Aurora Kiraly, with a project linked with the museum’s collection; we would host a series of workshops where the ones who answered the call would enter the collection and find their own way of interpreting it. It resulted in four exhibitions. It was the moment when we coagulated as a new group: Ileana, Marian, Ștefan and I. Other workshops followed but we never applied anywhere else.

We had a very good relationship with Mr. Oroveanu, in the sense that we would present our program early on and we would get excited to see young people at work. However there was a continuous ambiguity regarding the financing: I imagined that after the first year, in which we proved what we could do, we would be granted a yearly budget of a few hundred lei per project for production, fees and expenses for the space, we were hoping the museum would also pay us. We kept waiting for our status to change but this did not happen, probably because the museum was going through some changes at the time as well. After a while the problem was off the table, then it was on again, then it was all over.

Ileana: We were pretty excited about the first interim, Liviana Dan, who gave the impression she took us seriously. We had already found out our program was part of the museum’s program when it was reporting to the Ministry of Culture.

It was an ambiguous situation between a project space and a museum annex.

Simona: I can only imagine that, after a while, the museum, whose space at the House of Parliament was not visited as much back then, caught on that it could capitalize on what was happening with us and Salonul de Proiecte. Still, we never reported back to them, so I think they made their reports using what we posted on Facebook or on our blog. I think it was an unrepeatable, idiosyncratic situation: we were in a public institution, we had no status, no rights but no obligations either – we existed in a kind of bubble.

I think that there are no institutions – or off-spaces – in Romania that are clearly delimited. Most spaces live off institutions like MNAC or UAP [The Visual Artists Union]. In a way, all our institutions are in a idiosyncratic situation, there is no blueprint for an institution. Salonul de Proiecte had a different outcome, for example.

Simona: It was known that Magda [Radu, curator of Salonul de Proiecte] worked at the museum and that the museum allocated them, at least for a while, a certain budget. They managed to obtain other financing later on. We can assume that what Alexandra and Magda wanted – and managed – to achieve was rather a model of practice within an institution, while at the same time trying to distance themselves from it.

The goal of the two spaces seemed different to me, as well as the openness or the type of collaborations. You were in a seemingly similar situation, but with completely different aesthetic and political options.

Ileana: They were different projects to begin with. One common aspect was that they also wanted to work with young people, offer them a space.

Simona: An important distinction was that, following our open calls, there was no elimination process: whoever came to the workshop and stayed till the very end, would produce something that would end up in the show. The selection process seemed questionable because I don’t know who could have the farsightedness to choose or reject an artistic project. Any curatorial project that starts with this assumption is superimposing power and will over the power and will of people who want to do a project. After all, anyone who sends an application is capable of producing something that can be valuable under those circumstances.

I had a single experience which predates Platforma, where I was forced to make a selection as part of a group for the 2010 project Cities Methodologies. There was a huge number of applications for that workshop, especially since it was interdisciplinary; we had over 100 applications for a workshop that could properly function with no more than 20 people. I found the selection process very dry: I would ask myself which applicant would be more beneficial for the final product. It was like sculpting your own project out of people. I never liked that experience and I wouldn’t want to repeat it.

The only disclaimer we had was that we rejected those projects with any hint of discrimination – but it really wasn’t the case.

I’m thinking that if people knew there was no selection process, this also changed the way in which they would take part or the way they would interact with you, the hierarchy was perhaps lost. So basically, you answered positively to any proposal you received?

Simona: There were very few situations where we couldn’t say yes and every time it was because the space wasn’t available when the artist needed it. We only rejected a single project due to its content: we were doing our labor related workshops (First Shift, Second Shift, The Night Shift) and we were involved with this social discourse, while the respective project was in the jewellery and fashion design area.

So did Platforma turn into a space where people came simply because they needed a space to exhibit a project?

Simona: Yes.

Still, as you went on, did you start to receive certain types of projects? Were people censoring themselves, were they rethinking their practice based on what they perceived as fitting for you or did you also get proposals from non related areas?

Simona: I don’t know if there was any self-censorship. It’s maybe true that in the last two years, when the space functioned only based on open calls and workshops, the place had its own profile. You would probably show up at Platforma because you expected a certain type of practice, or you would come because you wanted your practice to be put to good use in that space.

Moving on with the narrative line of the place, after Marian and Ileana showed up, Ștefan left the team and Claudiu Cobilanschi came on board and, for a short while, Alexandra Șoldănescu, now part of the Quantic / Urban Collectors team and also producing her own feminist projects, joined us as well.

Ileana: She collaborated with us because she needed to volunteer during her masters program.

What was the scope of the project that involved working with the museum’s collection?

Simona: The initial statements highlighted the fact that these objects belong to us all, same with the history around them – the history of Romanian contemporary art – and within this mindset we wanted to be able to access it and interpret it, seeing as, since the museum;s inception and up to that point, no other specific interventions were made to the collection. It was also an opportunity for students to come into contact with the collection. We organized four art shows back then. The first, More than perfect, offered a reflexive approach to the collection: the projects interpreted details from Romanian art’s recent past and it was followed by an entry into the collection which resulted in Open for inventory at first, a project that did not exhibit the collection, but rather the participant’s various reactions to the content and the state of the collection. Mr. Oroveanu was very open in collaborating with us and told us all about the history of the collection and museum.

Ileana: Overall, I think we had an exotic vision of the collection. We were super excited and horrified when we first entered it. We saw a lot of works by important artists in the history of Romanian art that we studied about in school. The museum’s attitude, the storage conditions and the way the collection looked was revolting – it looked like an antique shop with full shelves, treated as if their content does not matter.

How were the works produced after this experience? Were they critical?

Ileana: I think they were candid. I replaced the old labels of the sculptures in the Annex collection with new ones. Larisa David left her own little piece with a label within the collection, asking herself when will her work be found. Marian also did a piece – he set some shapes on the shelves and spread dust around them and removed the shapes, leaving behind marks that made it seem like we moved things around the collection. Iulia Mocanu “hid” a map of the places where works from the museum administration were being stored – in the Annex, at TNB, at the People’s Palace and somewhere around the Press House area.

Simona: In Open for inventory, the whole atmosphere was very neat and everything was white, including the floors, covered by Marina Album with bubble wrap which makes a specific sound. During the opening people started rolling on the bubble wrap.

Ileana: This was the sound we heard whenever we visited the collection because every now and then we would find works enveloped in bubble wrap – for example a work by Geta Brătescu that we couldn’t recognize at the time because we lacked the visual culture to do so. Marina also did a piece with rat poison in the corners of the rooms where the collection was being stored.

Simona: Another intervention was done by Ştefan Bandalac – a scale that balanced pieces of artworks that were about to be scrapped with bits of wood. This is another very fascinating story – scrapping collection artworks. I suppose that the process takes into account the pieces’ physical state as well as their value.

Sabin Gârea did a piece using the sculptures from the museum’s basement that had missing bits. He made molds for the missing pieces and made new sculptures with them.

What mattered a great deal in organizing this exhibition was that mix of realist-socialist works and contemporary art pieces from before and after the 90s. There is a certain kind of perpetual ignorance on the museum’s part about what to do with the realist-socialist pieces that remain uncontextualized. That’s what Veda Popovici’s piece was about. She turned all the paintings over so only the very revolutionary titles written by the artists on the back were visible. Raluca Croitoru also used the work titles, she made a poem with them.

Open for inventory was followed by The Library – installing the Biţan library at Platforma – an immense and complex work with two very big shelves that contained remains of burned books. For us it was a reflection on the capacity to dislocate and relocate such an important work of art for the history of Romanian art.

The last phase was Romanian psychedelic which began with Ştefan Bandalac’s idea (Ileana: and a poem by Cosmina Ivanov) where we presented collection works that we chose and analyzed in a very personal way. We had the pieces arranged in the form of a carousel, performances with a bear, paintings included in optical illusions – basically just playing with the space.

Overall, this project lasted a few months. Back then we did not set out to explore an archive. We needed to see it and react to it.

Ileana: During the workshop discussions we asked ourselves all kinds of questions: What is the role of the museum? Why doesn’t it have a collection that is permanently on display? What will happen with the collection? Fundamental questions in the discourse that surrounds the institution.

Questions that have yet to be clearly answered.

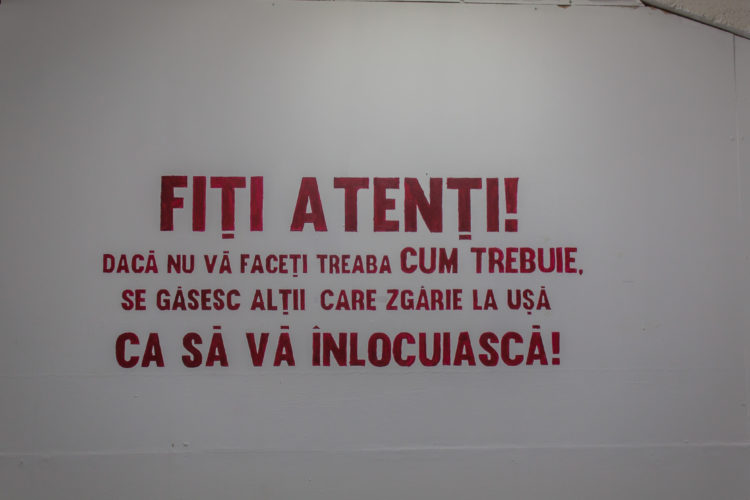

Simona: We’re approaching the end of Platforma. In 2014 and the beginning of 2015 we had projects related to labor – First shift, Second shift, The night shift that reflected on the niche preoccupations of the space, then there was From Aftershock to Immortality. Meanwhile we were hosting a lot of other events and punctual actions; to get an idea of the rhythm of the activities we did over the course of four years, we organized more than 80 events, take a look on our blog, the Facebook page for Platforma is gone. From Aftershock to Immortality, that started out as a theme related to utopia, distopia and post-apocalyptic scenarios, ended up reflecting our frustration for the fact that no one was paying attention to us, at least from an institutional point of view. The same issue was addressed in First shift and Second Shift, but in a more generic way, with a lot of the works referring to our labor and experience in the art world. It is very bizarre to have to produce our activity and having to constantly ask, to show evidence of what we do and demonstrate our necessity in the art scene. Sometimes you feel like there’s no one to demonstrate this to…

Ileana: Still, we never asked the institution for more than what they promised us.

Simona: I had the impression that Mrs. Balaci [museum curator, who went on to become the second interim director] appreciated our anti-institutional stance during Liviana Dan’s interim. The museum was invited to take part in Art Safari and was considering participating, and the director proposed we took part as representing the museum from an institutional critique stance.

Wow! So how did this stance turn into a farewell? The museum’s official statement said that the annex space had a high seismic risk.

Simona: Călin Dan, who asked us to meet him like the other directors before him, requested that we find a legal status and proposed that we, as a curatorial team that handled the space at the time – Ileana, Caudiu, Marian and myself – be paid by the museum via a collaboration contract, 800 lei each. The museum would then identify the exact contracting method for this collaboration.

The second to last big project was From Aftershock to Immortality – it started in September-October as a workshop, followed by exhibitions and performances. That was the first project where we followed the museum protocol as requested.

Ileana: The production budget was 400 lei for each artist – this is where Claudia comes in, who I met during on of the workshop’s first meetings, where we announced the budget and she said that she drinks the equivalent of 400 lei in one night. This ended up being her piece – she bought 400 lei worth of supplies for the apocalypse: alcohol, blankets, salt that we later passed around.

Simona: Then everything came to a halt. We got our promised salaries for 2 months, which also included part of the production budget. Although the rest of the production money and artist fees were promised, there was a very long period of uncertainty when we were just waiting to get the funds. That’s how the performance Waiting was initiated by Valentin Cernat. We glued ourselves to the walls and stayed there for as long as each of us could.

Ileana: Towards the end of Platforma, our relationship with the museum was marked by this uncertainty regarding money and our status. On one hand, the lack of money turned into a personal trauma and the museum’s reaction was extremely unpleasant – we were told during a meeting to get a job and stop begging – seeing as some of us actually quit their jobs to continue working at Platforma.

I see, you also promised the artists they would get paid and you wanted to keep your word. Still, how did the museum justify the fact that they didn’t keep their promise?

Ileana: We were told that the institution’s budget was cut short and that there is no money left for us. Long story short, we felt like we transformed from ghosts into a thorn in the museum’s side. In the end everything became very personal for us all, our relationship with the museum was not a very professional one.

Simona: We were told the Annex would close in the summer of 2015 after renovations and that it would reopen in the fall. Then we raised the issue whether we would return or not. Then came a period of filling out documents and official meetings. In reality, the plan was to permanently close the Annex.

This building had an aura of legend – it was built sometime during the 40s. It is said that Ceauşescu wanted to bring it down – the structure allegedly needed such a big quantity of explosives that it would have affected the surrounding streets, so it wasn’t demolished after all. This is why people with jobs in the building were under the impression that they were working in the safest place in Bucharest. However, after the expertise it seems that it has a high seismic risk. Perhaps it’s just an urban legend, but it is part of Platforma’s history.

Platforma closed down on the 12th of June 2015. Since working on From Aftershock to Immortality and especially during the performance Waiting we felt a heavy emotional baggage from all the people around us who would take part or just visit the space.

Ileana: A series of body and movement related workshops followed. Only girls took part in the workshops and we realized that we like it this way. With a feminist gain, certain people were drawn to the idea, others not so much.

Simona: I was under the impression that we got smaller and lost our ambition to demonstrate something to a large audience – I was left to my own devices. These workshops resulted in 3 performances. The first was How we got to 19.999 together where each of us counted numbers in the same space – it lasted around 10 hours.

This exercise had the goal of making us aware of the way we relate and function in the same space. It was also a way of building a safe space. The whole process was a construction of intimacy. And perhaps this brought us closer. After that there was Oac, Claudia’s masterpiece in front of the Ministry of Culture. I think it’s very relaxing to listen to it, a cool recording came out. Oac is all you’ve got left. Then came Scorpio Rising, where we worked with our own texts and porn films, with our own bodies and the image of a porno.

But curatorially speaking, this last event wasn’t the last hurrah because our final art show was the graduation exhibition for the Photo-Video department, something we did every year at Platforma and one of the reasons the space was associated with this department.

Your last projects were pretty statement, from counting to porno… Was it an outrageous gesture?

Ileana: From my perspective, it was not. The institutional tension and our reaction to that tension was gone – we had already channeled it into our previous 2 performances.

Did performing help you cope with the tension against the institution?

Ileana: I think so. It helped me face the facts, at least. I don’t know about the rest of the team.

Simona: The truth is that in the end it was just us two. Claudiu became indifferent, Marian was disgusted.

Ileana: The institutional context and Platforma as an entity took their toll on Marian’s relationship with art. He allowed himself some time to decide what he wants to do and now his life goes on.

Simona: It was an ending but also a beginning if I were to go full cliché. But us girls, we enjoyed working together so much…

Ramona: … for free!

Simona: Clearly for free! … so we still carry on working for free.

The Goddesses are more of an artist group, no? I am interested in discussing the relationship between curatorial and artistic practices. At Platforma you were a curatorial team whose purpose I always thought to be giving freedom to artists, facilitating their projects. Platforma worked as a stepping stone for young artists – do you still have a relationship with them, do you still collaborate?

Ileana: There were people who took part in every workshop. Even if it didn’t result in a project, they would attend the workshop for information or for sharing. Everything was shared, ideas included.

Simona: Indeed, I’m still friends with a lot of these people. The girls are very important for the current group, Local Goddesses. Many of them have worked throughout time at Platforma: Kiki Mihuță, Gabi Mateescu, Valentina Chiriță, Larisa David, Raluca Croitoru, Marina Oprea and current company of course. Part of the girls came along during our last workshops, Diana Joia, Venera Dimulescu, while others collaborated with the goddesses or got involved in the group post-Platforma: Diana Miron, Diana David while she was in the country, Alexandra Ivanciu, Doamna Dia, Roberta Curcă, Simina Oprescu. And the group is still open.

The history of Platforma holds many names, I couldn’t count them although it would be important to mention all of them. Other female artists participated in multiple projects: Marina Albu, Mihaela Drăgan, Veda Popovici, Anastasia Jurescu, Nicoleta Moise, Iulia Toma, Larisa Crunțeanu and so on. And some of the guys also took part several times: Bogdan Bordeianu in the beginning, Sabin Gârea, Valentin Cernat later on, Daniel Tristan, Petre Fall. And so many other, during each event, theater play, talks, concerts they were part of or simply for using the space as a workshop for producing their works.

I agree with the fact that Local Goddesses is first of all a group that considers its artistic practice, but I think we are trying to build a practice that includes curating, but not necessarily understood in an authorial way. Even the workshop calls were a followup to things we discussed together. The general formula is process-based, and everyone’s personal experience matters just as much, so does each of our preoccupations, which results in projects or calls to projects for others.

Is your way of working based on regular meetings?

Ileana and Claudia: Right now we can’t rely on regular meetings because the interior of our gallery is in unfavorable conditions: it’s very cold. We have a work group on Facebook where we exchange ideas, we sometimes meet at one of the girls’ house, we cook together, we have dinners. We’re friends too, not just collaborators.

Simona, you actually had a moment when you started to associate yourself more with a complete artistic practice instead of a curatorial or art history practice. You and Ramona work as an artistic duo.

Simona: I never disassociated the two. I think Platforma was your typical artist-run-space. Everyone had their own artistic practice. We would present our projects, as well as others’ during our workshops. I would take on the task of writing the artist statements, but I saw them as a superficial cover: underneath, it was important to show each individual’s process and work; most functioned as a generic introduction text, followed by the personal statements of each participant. I don’t get how someone can just be a curator. I don’t think you can clearly separate the two types of work process, one being artistic and the other curatorial, within a common route. For me, it’s like working with a collective work of art that belongs to me yet it doesn’t.

Maybe the roles change from a contextual point of view: sometimes you’re more an artist, other times you’re more a curator. Collaborative practices often migrate towards the artistic area rather than the curatorial one.

Simona: Your own project at Platforma, for example, was ethical from a curatorial point of view: you were there, but you were outside the process in which the people you invited were involved. This type of curating seems to me that it could function only as a role for facilitating. I can’t see how a curator could own the authorship of an art show.

I still think that curatorial work comes in not during the final claiming, but from the start, when the artists selection takes place. If you know their work, you grant them your trust, faith that there is a chemistry, communication. Then you just offer them a carte blanche and witness – and facilitate- the work process. I wonder if it’s not the same with you: the curatorial decision was to form the group, to own up to the fact that all of your actions will be under its umbrella.

Simona: Yes, with a few exceptions. Some of us set out invitations to other people to produce work in the gallery, but our curatorial work stops here. The rest is the responsibility, decision and statement of the guest.

Ileana: I think that, in fact, Local Goddesses do not set out to have a standard curatorial practice at all.

So then what is the criteria for inviting guest artists at CAV?

Ileana: We just have to like a certain artist.

Simona: Gabriela Mateescu recently invited Ioana Mitrea, who she knew for a long time and wanted to have a space to exhibit her works. It’s that simple. On the other hand, we recently had a discussion within the group on whether we should host an art show about pussy. It seems very cliché and over done, “let’s not be so obvious”…

Claudia: It all started with “let’s do something with lipstick” then it degenerated…

Ramona: … it generated!

Simona: … and we found another artist that talks about pussy that we’re thinking of inviting!

Does it have to have a feminist theme, or can the artist paint abstract paintings too?

Simona: Her work must be multimedia because this is the space’s profile. Performance art is included!

Ileana: And to be nondiscriminatory, of course.

The ones visiting CAV, are they also part of an extended family? When I came to your events, I always saw people who exclusively came there, even though the art world is very small.

Ileana: I am sure we have a core fan base, people who we enjoy keeping in touch and they like it as well, people who are our friends.

Your program also seems very specific, I perceive it as a willful delimitation, it feels a little inaccessible even.

Ileana: I think we sort of structured ourselves into a support-group, a group for helping one another.

So then why is there a need for activating in a public space?

Ramona: So that people can come in! Ever since we’ve been at CAV, I’ve seen many new faces, curious people who come into the gallery and asked us what’s going on, what’s happening here.

Simona: Maybe it’s a bit early to tell, but I think that due to the space’s positioning, its street view, makes it more accessible than Platforma, where you’d only go see the openings. The gain of a public space is the possibility of a message reaching out to more people.

Ileana: We need this message, it needs to be made public: girls for girls, women for women.

Claudia: Why do you find it inaccessible?

In the sense that it has the emanation of a private group that one has to accept: it’s like when you visit a family’s house, you don’t have the necessary neutrality, you’re either on the inside and you feel great, or you’re in the position of an observer, a bit indecent even.

Ramona: Maybe from the point of view of someone who knows the art scene and its cliques. Some stranger on the streets who walks in and sees Mrs. Ena freezing to death and some movie projectors won’t have the image of a family.

I am referring to the people who come to your events because they know what’s happening there.

Ramona: The exhibitions are frequented by mostly the friends of the artists who don’t necessarily know that we’re the organizers. There is not a strict correlation between us and our performances, and the CAV exhibitions.

My question is if your message – your attitude, your principles – are meant to reach people, or if this is your way of delimiting yourselves, cutting off from the rest.

Simona: Right now I think we have a very mainstream position within a radical stance, because if we were a radical group, you wouldn’t have heard about us, or we wouldn’t have access to means of expression because we didn’t need them or couldn’t get to them; the same goes if we were marginalized or unprivileged. On one hand, there are very different ideologies and political orientations in this group: not all members are interested in a feminist discourse, nor do they assume a feminist form; some are involved and talk about artistic practices. There is no feminist flag on every exhibition we organize – the common denominator is more the idea of exploring strictly personal experiences, such as “I am a woman, this is my narrative, this is how I lived it, etc.” This is probably the reason behind the intimate feel of our projects, which may appear to be restrictive, depends on who’s watching.

What kind of feedback do you get on your projects? I am trying to figure out where does a feminist discourse fit in our society, in the art world and in our lives.

Simona: During our 2015 Tranzit event (Moving Heads) we got feedback from some of the people we know that are not part of the art world but share our feminist preoccupations. They didn’t give me an artistic feedback, but they talked about the works from their own personal points of view. After our first CAV project, we got feedback from people close to us. Besides that, we had no theoretical feedback – in 4 years of Platforma there was no text written about our activity. Maybe the best feedback is the fact that people kept coming back to our events.

I find this lack of theoretical feedback to be symptomatic: Platforma had a coherent activity and identity over a long period of time which was dully noted but never articulated. Maybe it’s better this way, it contributes to forming an anarchist myth around the space.

Simona: I was frustrated about this for a long time.

Ileana: At one point, Erwin Kessler gave us as a counter-example for an art show that was happening at The National Library.

Claudia: If we’d have money, maybe they’d write about us too.

Ramona: Having a feedback also implies a value judgement. It’s irrelevant for me: if much is written about something, that thing is not necessarily valuable.

Ileana: The best feedback was from those who kept answering our calls. There were talks in the school hallways, cliques that were pro-Platforma or anti-Platforma. There were talks about money: the anti groups saw us as poor, the pro groups were saying: “poor as they may be, I still wanna learn what it’s like working in a space.”

So why didn’t you apply for AFCN funds?

Simona: We did once.

Ileana: We also applied to the Venice Biennale the year Adrian Ghenie was selected.

Simona: Speaking of financing, I found the situations to be contradictory. I thought we could overcome it when MNAC seemed to be offering us a budget. The problem was that financing could be granted for a few projects, but what to do with those who worked before this moment, or who were going to come after who weren’t getting paid? The feeling was that some were sacrificed so that others would get paid. We chose to function independently, between the contradictory limits of those who we could have paid and those who we couldn’t have paid.

This also meant limitations: you couldn’t invite foreign artists or make publications for example.

Simona: Yes, we would have exhibited foreign artist too if they were already here. Anyway, there are so many things we need to do for the people around here, our priority really wasn’t working on an international program.

Ileana: When we hosted international projects, the condition was that local artist could take part without fees – like the performance festival organized by Valentina Chiriță in 2014, IPA.

Simona: I’ve since gave up on this pride and I think it would be wonderful if we won an AFCN grant. But I think we should be careful with those who would work in the space with no financing. Grants come and go – these ideas should be discussed.

I think this is also a political option: always organizing art shows with no budget will not lead to an area of professionalism, in the sens that a professional artist earns his living from making and/or selling art. This is also a refusal to the commercial area, but also to the very condition of the artist whose work is automatically labeled as art and this is why it cannot have a political impact, it always stays in the art world. The gallery space itself is a safe space in this sense, anything you do within its walls, no matter how radical, risks being read as “just art”.

Simona: At the end of this year at CAV, we will have produced a program with women only, which will leave its marks on the local imaginarium – it will go beyond the status of “just art”. At some point, some are bound to become frustrated, some probably are.

Claudia: Our way of action is a political decision, at the same time it is a transitional period. However, I don’t know if AFCN finds the feminist discourse all that alluring.

Simona: The feminist discourse is perceived as insufficient motivation for financing, or at least that was the case when we applied for the multi-annual funds last year. Technically speaking, it was a well written project and justifiable within a personal language for our discourse as a group, if I do say so myself. We thought of applying again and removing from our application all the feminist references, art for women, spaces dedicated to women and see if our project is accepted. Obviously, it was bad practice; and if Gabi would have joined this discussion, she would have told a completely different story: rather than not applying at all or giving up too easily, she tried various times and was constantly rejected. Nucleu and the projects she did along with Tăietzel Ticălos and their collaborators are proof that they are not given this chance. So the experiences are very diverse, but the general habit of work is from grant to grant. Yet this type of M.O. often excludes me: it is so institutionalized that I have the feeling I am already excluded before ever applying. These groups that try to activate with no money are the result of all the other groups who very well know where to apply and how to get funds.

POSTED BY

Cristina Bogdan

Founder and editor-in-chief, between 2014-19, of the online edition of Revista ARTA. Co-founder of East Art Mags, a network of contemporary art magazines from eastern and Central Europe. Runs ODD, a s...

www.evenweb.org

Comments are closed here.