Interdisciplinarity is not just about combining methodologies, but also about the capacity to navigate around them, to handle a hybrid-situation that could give birth to a new creative medium. Looking back on the art of the 20th century’s last decades, it becomes evident that, in order to have certain micro-climates or contexts that can generate something new, there has always been a dominant situation of incompatibilities, social or political rifts, and disparities. In Romania’s 2000s, poor fusions and assimilation between sources, tendencies, ideas and incompatible formulas have developed the ability to function as a hybrid. During the 2000-2010 decade in Bucharest, contemporary art came from an area where the practices, disciplines and methods were not very distinct. Bricolage and improvisation are a necessity for creating culture in uncertain conditions. In the article “The Culture of Shortage during State-socialism in the 1980s” published in Cultural Studies 16/2002, Romanian anthropologist Liviu Chelcea analyzes informal practices related to the material culture within the socialist context. For Chelcea, the way in which objects are created and used and the reinvention of essential functions for this time, are closely related to ritualized social relationships.

In each of the following case studies, in which cultural creators talk about this moment, there is a type of interdisciplinarity that transpires, where art (in order to be made possible) cannot happen only within a community, it must also come in relation to various other cultural fields (club culture, bars, alternative artistic spaces, technological experiments). During this time in Romania, art was partially formed due to phenomena that are not specifically artistic, but rather divergent to cultural activities, with little financial means and the minimal infra-structure that was available at that time. This type of do-it-yourself culture practiced during that period in Romania, which will be presented below, is fundamentally different from the interdisciplinary approach of the artistic and academic context of Berlin, for example. Here, or in similar frames where inderdisciplinarity is rather an analytical method, high art (even if it was independently cultivated) enlists and “artifies” other disciplines in order to become ever more sophisticated.

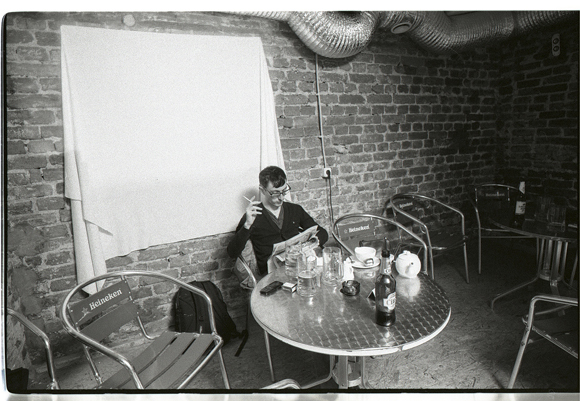

The first of our short interviews is with Octavian Rusu, the founder of the Ota space in 2003, where famous soups, a contemporary art gallery (Gallery 26) and an art shop in his own home, formed a place that was favorable for the flux of ideas and bought together musicians, artists and curators. Similarly, the deBUFET terrace at the art school gallery (UNA gallery) courtyard, with the artists Nicu Ilfoveanu and Mihai Cosma in charge, was a hangout place with bohemian charm, good wine and open air movie nights.

Octavian Rusu: It all began with a painter friend of mine, Horia Cadariu, who wanted to make an art show, and my idea of hosting a gallery in my own home. I met Anderiana Mihail who invited Nicolae Comănescu for an exhibition and we have been good friends ever since. Three more exhibitions curated by Anderiana Mihail and Florin Ciulache, among others, soon followed. Then, Adrian Bojenoiu, who is a philosophy graduate like Andreiana, curated a few other shows, including one with the graffiti artist Zanga (Dani Macovei) in 2009, a prolific artist that was first introduced by DJ Tom Wilson, who also collaborated with Atelier 35. We also had an art show for Gabriel Giodea, curated by Adrian Bojenoiu (Made in China, 2009).

At the same time, we had a bar that accompanied this whole process and kept it financially afloat. We never had funds for producing the exhibitions, the artists would bring their pieces and everyone would work to put up the art show. It was a place to escape to in a time where there wasn’t a similar spot in Bucharest, and dancers, actors, curators and artists, Dan Popescu, Gorzo, Gili Mocanu were here from the beginning, they always came together. We did Nicolae Comănescu’s show in the attic of my house, and later as part of The Contemporary Art Shop (in Romanian, it ironically has the same initials as MNAC – The museum of contemporary art). The idea was to annually host an art fair where every work was valued at 100 euros, but then we turned it into a shop for good things and less good things that weren’t necessarily made to be sold as expensive items, but rather to present a Nicolae Comănescu alongside young unknown artists. At first, business was booming, but then there wasn’t anyone available to take care of the store or the gallery because every one of these curators were already involved in bigger projects. Simona Vilău, Lea Rasovsky and Alexandru Davidian have also recently curated. We also had diploma projects for students that graduated.

But the project might die soon, even the bar is working at only a third of its capacity. I am currently renting the space for yoga lessons, this way I can cover some of the costs. The public changed, this place isn’t as cool as it used to be, but people still come here from an opening at Salonul de Proiecte, Marian Ivan, Zorzini or MNAC. Still, the constant fervid atmosphere the used to be, is now gone.

Testpoint, the old sock factory on 11 Iunie Boulevard in Bucharest, was conceived by Niki Tutuianu and Cristi Ravoiu in 2004 as an independent space for building a new urban culture and reinforcing a solidary artistic project with Romanian and international graphic artists, musicians, VJs and DJs. In 2006, Testpoint was a place that hosted some of the Bucharest Biennial connected events.

Niki Tutuianu: Before the factory, I organized illegal parties in abandoned houses all over Bucharest in 2004-2006. They were initially called Substil, and then Transfer in collaboration with Tralala Events. We would rent a house for the night and we would built various musical scenes, from drum & bass to experimental music, and artist spaces where they would make performance art, projections, live painting. We needed a permanent space so we rented a factory that had been abandoned for 10 years and called it Testpoint. After we took the factory, we had just one month to rebuild it. There were only three of us working, with help from skilled friends, but no professionals were ever involved. During our first party, the toilets were still out of order and the walls weren’t dry yet, but 800 people showed up. We started having events every two weeks, sometimes even weekly, which were funded by the money we made, with no initial budget. We collaborated with The French Institute or with Metacult to invite foreign artists and DJs. During large scale events at the MNAC, or Rokolective events, the public would come to Testpoint for after parties. We were behind on our electricity bills and rent, so we were forced to associate ourselves with investing partners that allowed us to bring international DJs and organize bigger events. These partners basically took over because we never invested any money in the business. It was important for us to maintain the industrial vibe with a certain design, so we invited sculptors and designers that worked pro bono. But the original aesthetic had been immediately changed with the arrival of the new owners.

After going bankrupt in 2010, Testpoint was taken over by 5 shareholders that radically changed the place and called if Fabrica (The Factory). Costin Stănicioara, one of the current owners, sums up his present activities: When we took over Fabrica in 2010, we proposed to the owner to rent out the whole place and subleasing all spaces that made up the 3000m2 of land. I didn’t care much for the electronic music scene, so I turned the place into rock music club. Now we own two clubs, pubs, 10 stores and a playground. We don’t have designated spaces for art, but we do host photography, painting and handicraft art shows in the yard or in the restaurant once every two months, as well as an advertisement festival called ADFEL. We receive art show proposals and we never ask for rent money, we do it for the exposure.

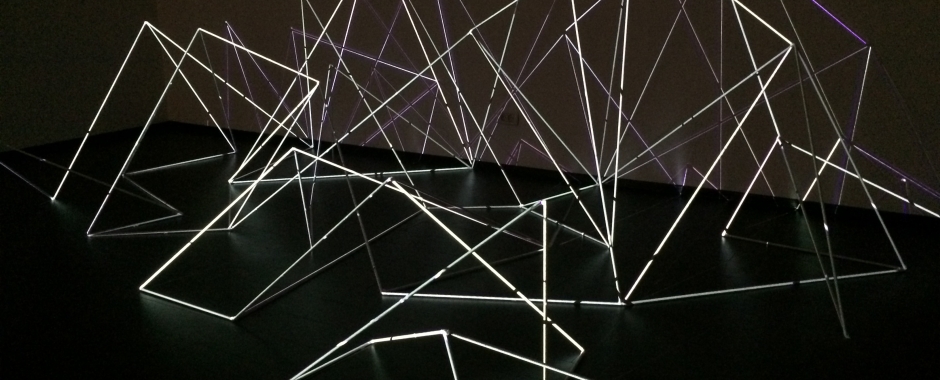

A space that has just been inaugurated recently is Modulab, which defines itself as “an interdisciplinary laboratory for art, technology and design”. Opened in 2010 by Ioana Calen, Matei and Paul Popescu, this spot is a relevant example in this case, because it provided contemporary art with a path to the practices of the digital world. But also, and especially because do-it-yourself is not seen as a provisional solution, but as an example of functioning that is also financially self-sustained.

Ioana Calen: Paul Popescu studied design, in 2008 he worked at the MNAC media lab and before that, in 2006-2008, he had started to specialize in digital tools using online tutorials. I was writing for the Cotidianul about new media and digitally augmented contemporary art and Matei was handling production and technical innovation. But Paul is the glue that integrates everything. We needed a place where we could pass on everything we learned in this field. We knew that if the scene around us does not grow, our value will also drop. Our discourse was: democratization of knowledge, very little funding, learn everything online. In 2010, we turned a garden into our headquarters where we built everything ourselves, just like our motto says. We applied for local funds (AFCN) to hold free workshops. Modulab Garden was inaugurated with a huge party where we talked about our philosophy and we had positive feedback from designers, architects and artists. Our commercial clients, who commissioned hologram installations, mobile apps or interactive bars were also very pleased, even though this type of culture was not present in Romania at that time. For us, these kinds of projects are simple, with no creative value, but they help us finance the space every 6 months, host pro bono events or pay the people we work with.

It is a synergistic situation. We work hard in the contemporary art field as well: Mircea Nicolae recently hosted a presentation on art and technology from a theoretical perspective. We made a piece inspired by The Infinity Column, that we remixed based on hologram like algorithms, for the inaugural party at the new ICR Berlin HQ. We also work with contemporary dance, we’re working on technological solutions for corporal prolongation and motion tracking effects. In 2013, we organized what is probably the first interactive installation art show in Romania, Symbio Morpho Genesis at MNAC. The technology used was designed as a non-biological species that imitates biology and uses man to evolve, becoming more and more intelligent. If there’s one thing you can say about us, it’s that we manage to build these kinds of projects with limited funds while, in an international context, these projects would be granted 10 times our budget.

Initiatives from any other field that connected with contemporary art, creating new platforms, were essential for the cultural scene. Basically, the only cultural fund, the AFCN funds, was the only official way to invest in cultural production, and people from all areas apply. Farid Fairuz’s projects, The Cultural Home and Sub-Rahova (organized by the Solitude Project GNO), which are dedicated to contemporary dance and are located at the outskirts of Bucharest, were designed to be exhibition spaces as well, and many consistent collaborations between the two artistic fields took place.

Along with these interdisciplinary collaborations, cultural surviving techniques specific to the Bucharest art environment, they developed a multitude of novel functional, experimental and personal structures.

Connected to the National Museum of Contemporary Art and conceived primarily as a production space, the MNAC Anexa space was an essential pillar for the art scene. Although always poorly financed and frequently sustained through personal efforts, this frame has kick started spaces such as Platforma and Salonul de Proiecte. Platforma, for instance, has extended its activities well beyond a mere exhibiting context, towards a structure that covered various gaps in the Bucharest urban culture: queer culture, alternative trade economy experiments, spoken word meetings, ecology and sustainability debates, liberal work models etc. – creating networks meant to last and facilitate cultural production.

A personal initiative which promoted and bought visibility to alternative spaces is the Galleries’ White Night, put together by the artist Suzana Dan and financed by Raiffeissen Bank. Looking back at the nine editions starting with 2007, these events make up an important archive for the commercial galleries, the spaces, projects and collectives which held their ground during this decade or have meteorically appeared and disappeared or have intermittently functioned on the Bucharest scene. Suzana Dan has also coordinated Art On Display (with art shows in Bucharest’s window displays), as well as the Galleries’ Weekend, a diurnal alternative to the galleries’ night that just took place at the end of this month.

Another space connected with a trade union structure – The Artists’ Union – but effectively functioning through personal efforts is Atelier 35. In the 70s, when it was founded, it introduced the idea of a network of spaces throughout various cities in Romania, which implicitly connects young artists and experimental practices. In theory, it was reserved for artists under 35 years, considered at the time to be the conventional age limit of youth, and it was run by a diverse group consisting of artists, curators and theorists drawn towards experimenting. During the communist period, Atelier 35 was an alternative to the persistent pattern of galleries reserved for the members of the Artists’ Union, for art approved by “the state”. During the transitional period, Atelier 35 encountered many delusions, conceptual cracks and shifts, thus losing its avant-garde characteristic. In 2007, after a long break, Daniel Alexandru, Raluca Doroftei, Vlad Ionescu and Roxana Patrichi took the name Atelier 35 and gave it to a space dedicated to young artists during a time in which these types of spaces were completely out of the picture. Silvia Saitoc and Matei Sânmihăian took charge and proposed a more firm curatorial approach centered on post-internet art. Atelier 35 is currently run by Xandra Popescu and Larisa Crunțeanu who work together as both artists and curators. The duo focuses on the multi-functionality of the space and on blurring the boundaries between experiment, production and exposure with a focus on video and performance, Atelier 35 being one of the most active alternative space in Bucharest.

The majority of art projects are still, to this day, supported through volunteer efforts and minimal financing from foreign cultural institutes or European funds. This situation determines the compensatory character of artistic production and the need to create space for art forms that have been historically absent from the Romanian scene. At Paradis Garaj, a space initiated by Claudiu Cobilanschi and Ștefan Tiron in a garage and a yard, the alternative was the house specialty. Programmatically, their events have operated between structures in order to maintain the off-zone promise, the pop paradise of the 80’s that inspired their name (a gay club from Soho, New York).

The Bureau of Melodramatic Research, the duo consisting of artists Irina Gheorghe and Alina Popa can be seen from this perspective as a nodal point for various performative practices, aiming to reveal the emotional plane and baggage (often reminiscent of the communist era) which dominate the Romanian society.

Various forms of association between artists and curators have generated frames that were not only dedicated to alternative production, but to an analytical perspective of producing art as well. The Center for Visual Introspection belonging to the artists and curators group Anca Benera, Arnold Estefán, Cătălin Rulea and Alina Șserban made a lot of research projects possible, with the help of personal networks and international collaborations.

Looking back on these initiatives, it becomes evident that DIY strategies in Bucharest outrank the official ones when it comes to production force. They influenced not only the aesthetic, but also the theoretical discourse that maintained it and managed to build, in time, a certain political culture. They raised questions like the specific tension between the official and the alternative discourse, local and international practices, problems related to cultural responsibility and the representativeness of these practices for the post-communist period.

Right after I had finished this article, the fire that broke out in the Bucharest Club Colectiv, which left many dead (49 people that died and many more injured), started a huge political turmoil and led to the fall of the government. The fact that this club did not have authorization for the number of people that it hosted, is part of a complex administrative system filled with gaps, corruption and indifference. The spontaneously formed 4 day street manifestations triggered by these events and a deep dissatisfaction with the unqualified political class, were an eye-opener for the civil society and the political class. The prime minister and the members of the government resigned and President Klaus Iohannis invoked not just the political parties but the civil society (non-governmental organizations and for the first time the representatives of those who manifested in the street) as well, in order to solve the situation and elect a new government.

POSTED BY

Marta Jecu

Marta Jecu is researcher at the CICANT, Universidade Lusofona, Lisbon and freelance curator. She has published in magazines like: E-Flux, Kaleidoscope, Berlin Art Link, Idea Art+Society, Journal of Cu...

www.martajecu.com

1 Comment

A note on the last paragraph:

In light of recent events, the future of alternative venues (obscure places, abandoned industrial areas and so on) is at considerable risk. A lot of clubs and galleries that were important for the evolution of the scene may vanish very soon.