The exhibition project Community in Solitude, curated by Andreea Căpitănescu at WASP space, represents a recontextualization of the existential issue of dwelling during the COVID 19 pandemic, a period of isolation that augmented the virtualization of life. The exhibition therefore eloquently captures the fact that dwelling does not mean possessing just any space, cannot be reduced to an address in your ID. It refers rather to a home where you find yourself, a home which for the artist can be a studio, or for a performer, the performance room. The four projects in the exhibition deliver an artistic phenomenology investigating the relation between “to be” and “to dwell,” between the individual’s identity and the architecture, landscape, and space (physical and virtual) that they inhabit. Started by phenomenologists like Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty, applied to architectural theory by architects like Christian Norberg Schultz, the discourse around dwelling insists on the fact that we are what we are according to our buildings and landscapes, and also that there is a natural extension between our body and the world. The digital age only moves things one step forward. In this context, with finesse and mastery of new technologies, artists Matei Bejenaru, Andrei Mateescu, Gabriela Mateescu, Liliana Mercioiu Popa, and Ghenadie Popescu propose an analysis of the virtual mutations and the avatars of the so-called home in the (post)COVID age.

Liliana Mercioiu Popa’s site-specific installation, a theatrical representation on a 1:1 scale of her apartment, certifies the aforementioned phenomenologies through its suggestive title: From where to where does my person extend, where do the others start? Conceived during the pandemic, when the artist, finding herself stuck at home, worked till late on her computer and taught painting online to her students in Timișoara, the project delivers a captivating interpretation of the crisis of space and body. It is suggestive here to look at the installation’s configuration, an apartment that has been essentialized to a simple outline, reminiscent of Dogville, Lars von Trier sketch-city. Placed at the intersection of the virtual and the real, Liliana Mercioiu’s apartment’s walls are a thin, transparent plastic veil, and it is populated by white sentinels, small robots made from mini-vacuum cleaners, which, besides the DIY aesthetics, recontextualizes the technological enthusiasm and poetry so prevalent in the late sixties, when the interdisciplinary group Experiments in Art and Technology launched their collaborative sculpture Pepsi Pavilion at the Osaka World Fair.

The permeable, almost immaterial walls tremble, they react when each visitor passes by, they breathe like a living body, allowing thoughts to pass, fostering a spatial continuum like the one Fontana made by cutting his canvases in Concetti Spazziali. It is also remarkable how the Apollonian scenography, the state of daydreaming and contemplation favored by the darkened interior, the veil walls suspended from the ceiling, intersects with the need to act, to move, with the Dionysian escape from the self into the world. The encounter between the human visitors and the robots is encouraged, as is the active, insistent gaze specific to contemporary art.

The first piece of evidence that the long pandemic days spend in front of her own virtual image connected to other virtual people gave the artist important phenomenological insights is that her fine analysis employs a qualitative-affective connotation of spatiality. Liliana Mercioiu Popa distances herself therefore from a mathematical Cartesian interpretation of a homogeneous and aseptic space. Another piece of evidence is the way the artist makes her body escape its limits, its skin, the way it transforms itself, as phenomenologists have noted, into an active, present body, in a veritable chain of sight and movement that is irreducible to a bundle of functions (Merleau-Ponty). In this sense, the body becomes one with its projection in the world, it incorporates paths and territories that are haptically or virtually conquered, it becomes an extension, how far you can see, know, touch. It must be noted that this phenomenological interpretation of the body offers an answer to the fears instilled in people in the COVID age of isolation. An isolated body is an amputated body, a body cut off from the world, from the fabric in which it is often integrated together with other things, other bodies.

Liliana Mercioiu’s project leaves open the question of how capable virtual reality is to solve this crisis. The question is however be taken up by the other projects in the exhibition, all produced during the pandemic and accompanied by a series of discussions about the orientation of the contemporary artist between the pole of community and that of solitude, which were mediated by the exhibition’s curator.

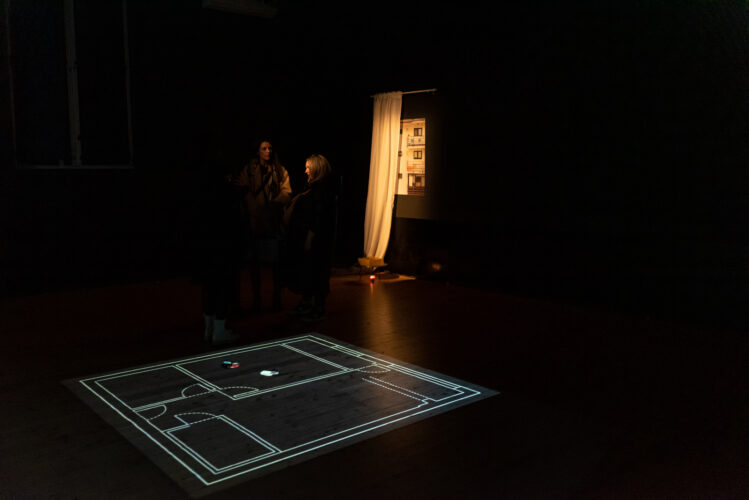

One relevant answer is delivered in a playful tone by the project IZOLAREA / ÎNAINTE, ÎMPREJUR ȘI ÎNAPOI (ISOLATION / FORWARD, AROUND, AND BACK), by artists Gabriela Mateescu and Andrei Mateescu, a digital video installation that outlines the topography of the apartment where the two spent the pandemic. The place’s architectural plan is projected onto the floor, where the visitors-become-voyeurs can watch the evolution of the two characters, who act, filmed from above.

The restricted space of only two room sis traversed in cycles, transformed into a ritualistic, affective-labyrinthian space. The two approach each other, meet, then retreat into different rooms, they double themselves occupying the space while also delivering a topographical interpretation of a relationship. We may ask ourselves how much the map of a love depends on the trajectories and positions of bodies. Vertical positions, reduced to a top-down view are combined with those stretched horizontally, together or separately, book in hand or arms under their head. The speed of movement through the rooms is added to this. What one gets at the end is not just an interpretation of a relationship but also an explicit view of dwelling, of space. Here we see the two lying down. There might be a bed here. This must be the bedroom. The living room must be over there.

I recall Georges Perec’s notes in Species of Spaces regarding the functions of rooms. If stairs represent the common space that we often ignore and doors function as barricades separating, protecting, stopping us, the bed, a space in which we spend more than a third of our lives, can turn, when lying down on it, reading peacefully, into “a baobab tree threatened by fire, a tent erected in the desert.” The Apollonian, contemplative dream, the possibility of imaginary travel, bring back to mind that quote from Pascal that curator Andreea Căpitănescu chose as the exhibition’s motto: “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

As Pascal noted, humans need the company of other humans, and yet being together authentically is no easy task. Most often, this together most often reverts to conforming to conventions or to a competition for resources and territories. An example of an impersonal, inauthentic togetherness is discovered by the same Perec in the program and strategies of the occupation of living space employed by a standard family: at six-thirty the father enters the bathroom; a quarter of an hour later, the mother takes his place; at eight in the morning the family comes together for breakfast; at nine in the evening they reunite before the television, etc. How can we be ourselves if we live in a matchbox, if our schedule, the trajectories of our every day, the consumerist function of each square meter of space are pre-established. Putting the video installation side by side with a photographic one whose central piece is the image of the apartment building located a few meters from the window of their apartment, Andrei and Gabriela Mateescu pick up Perec’s question about how various means of destabilizing the functions and occupation schedule of rooms can lead to a veritable liberation of space. Who better than an artist couple to teach us what a free relationship with space might entail?

The pandemic period, when not only distant journeys and destinations, European sites and museums, were put on hold, together with regular trips to studios and exhibition openings, certainly revealed the fact that the artist’s touch, sight, and body must be able to reach far and wide. In this sense, the limitation of this gaze, synonymous with the amputation of the body, threatens the condition of the artist as an artist.

A discourse on the gaze was also delivered by Matei Bejearu, a famous artist and professor at the George Enescu Arts University in Iași, a true practitioner of social art, of archive projects, and projects about communities, whether they concern the peripheral neighborhoods of Iași or towns on the other side of the Prut. Besides his interest in migration and poverty, one notes an openness towards collaborative art projects, which led to the formation of a Iași school of video and photography, as well as a strong artistic research community, around him. Still, despite this undoubtable openness towards others, Matei speaks in his conversations with Andreea Căpitănescu about his moments of solitude. And it is not just about the pandemic or the nostalgia of the professor forced to say goodbye to a new generation of students every year, about the so-called changing communities in academia, it is also about the artist’s need to withdraw, together with his camera, in his studio or in nature.

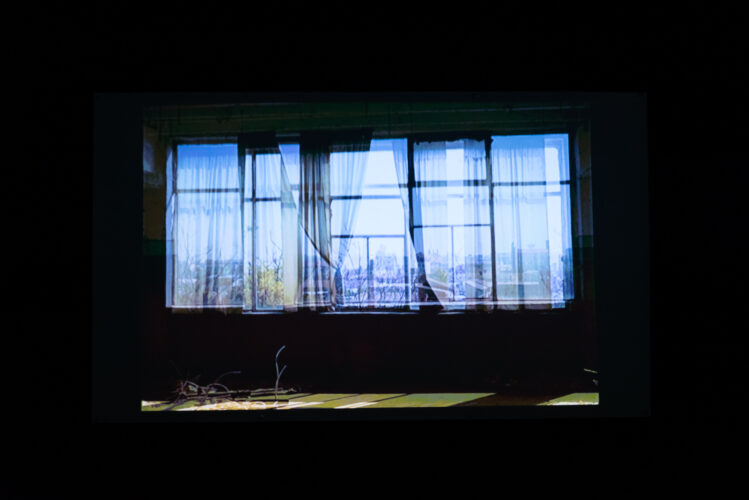

In this sense, his work From A to C is a discourse around the gaze and language, where the metadiscourse of the gaze mediated by technology plays an important part. And this is not just about the truthfulness and increasingly strong impact of virtual reality and artificial nature, it is not just about being aware of the fact that every day our contact with the world is increasingly based on filmic, photographic, and digital representations. The artist puts forth specific, intriguing questions, such as: why do we increasingly talk about the landscape as a species of photography? How can we use filmic markers, colored squares that control exposure as visual signs? We may also note that, in an age of the technical image in which critiques related to the loss of the aura, authenticity, and contemplation have been taken up multiple times in various registers, from Heidegger to Virilio, Matei Bejenaru’s position is rather appreciative. His “lover’s discourse” (Barthes) towards the poetics of the grainy image, the recorded image’s play of indeterminacy, invokes the way director Robert Bresson referred to his camera and tape recorder as “sublime machines of divination.” Matei Bejenaru’s interest in technical aspects and new experimental possibilities recontextualizes, in a postcinema age, André Bazin’s view of the technique of cinema as a veritable metaphysics, but also an entire wave of contemplative cinema (Antonioni, Apichatpong, Abbas Kiarostami, etc.) which managed to restore film’s status, reconnecting it to aesthetic value without it losing its socio-political meanings.

But placing From A to C on the theoretical maps of experimental film is not easy. If the interest for the metadiscourse of the mechanical eye places it somewhere between Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera and Michael Snow’s structuralist experiments (see the automated recording of the landscape in La Région Centrale), the work’s deeply affective atmosphere puts it close to surrealist discourse. Undoubtedly, the film is an archive that evolves between documenting certain abandoned postindustrial sites at the edge of Iași and noting the glory days of modernist architecture and communist achievements in a series of postcards: hotels, beaches, highways, and industry. At the same time, it represents a collection of sights and effects of the movie camera: industrial objectives and postcards recorded from the front, pan shots of the industrial area captured from one of the city’s tallest buildings, recordings in the forest, immersive ones at grass level or, on the contrary, slow, contemplative ones filmed from a drone, close-ups in which the Akai tape recorder, the drone, the camera, and the film become characters themselves.

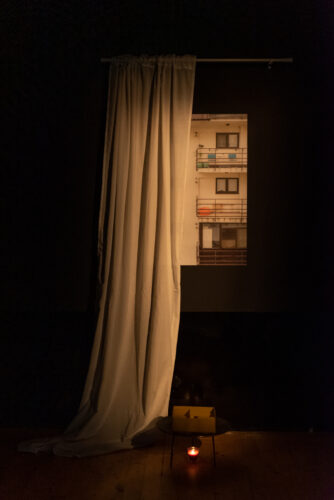

On the other hand, the video represents a confession, a personal account of the moods the artist went through during the COVID 19 crisis. The closeness of death, the isolation, solitude, and refuge into the woods near his home are a second level of his discourse, this time based on props and dramatic effects, such as the black curtain that can be seen both in the artist’s studio and, unexpectedly, in the forest. The juxtaposition of this window into the unknown with images from the woods and juicy close-ups of tropical plants reiterates the famous Freudian Eros-Thanatos duo, while also recovering Derrida’s definition of the archive (fever). Under the sign of the same Thanatos lies Ghenadie Popescu’s sculpture Leukos. The Quickest Response, a QR code made of plywood that links to personal vaccination data or, why not, to an episode of the recent war in Ukraine. We return to Pascal’s words, demanding a stop to the aggression, calling once more for an exercise in peace, be it in solitude or together.

The show COMMUNITY IN SOLITUDE took place at WASP Working Art Space and Production during 20.04.2022 – 15.05.2022.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Raluca Oancea

Raluca Oancea (Nestor), member of International Association of Art Critics (AICA) and European Network for Cinema and Media Studies (NECS), is a lecturer at The National University of Arts in Buchares...

www.Dplatform.ro

Comments are closed here.