Some months ago, I wrote about an exhibition containing some fragments of the famous, though lesser-known in Romania, Transylvanian Panorama,[1] painted in 1897 by Jan Styka and his international team of painters.

The curators tackled the idea of emancipation itself as well as the continuing struggle for bones – in other words, necropolitics. And so, the exhibition moved to Białystok, another Polish city, where, in a new context and under pandemic conditions, but with reinforcements, the art workers – curators, gallery owners, and artists – took up offensive positions. The exhibition they designed was called Spring In The Józef Bem Housing Estate, a late spring, in tune with the diachrony of some of the works. This time, the curators built their discourse around the holes left in the Transylvanian Panorama and in history itself, either missing or under threat, as well as around the processes that make this fact a deadly commonplace.

They made sure to include Józef Bem’s mausoleum in the exhibition, Bem being the hero of the Transylvanian Panorama, whose alternative title is Bem in Transylvania. He also appears in an oil painting by Paweł Baśnik. This work is part of a series dedicated to atypical national heroes, those who do not neatly fit the framework of nationalist or statist discourse.

Roma People in the Transylvanian Panorama

In the new exhibition assemblage, the actual fragments of the Transylvanian Panorama were not present, being replaced with a new visual interpretation. The new, quite large-sized Panorama was the work of Krzysztof Gil made especially for this exhibition. Being aware of the educational aspect of his undertaking, not a fashionable one in contemporary art discourse, Gil dedicated his work to a part of Romanian history that we do not like to remember – Roma slavery in the Romanian principalities. In the Transylvanian Panorama there was a Roma taraf [a musician ensemble – tr.n.], soothing the resting revolutionaries with their music. Gil argues that that particular fragment in the Panorama is an echo of a romanticized stereotype: Roma people were often represented in medieval texts as merrymakers, musicians, and idlers. Meanwhile, one of the great achievements of the Springtime of the People was the attempt to completely abolish slavery in Moldova and Wallachia.

Viorel Achim observed in his book The Roma in Romanian History that the first partially abolitionist laws were passed in 1843, leading to the freeing of state-owned slaves in Wallachia and in 1844 in Moldova, and, shortly after, in 1844 in Moldova and 1847 in Wallachia, church-owned Roma slaves were freed for a compensatory fee of eight to ten gold coins.

The failure of the 1848 revolutions did not mean the abolition of slavery but the stagnation of the emancipation process of slaves held by property owners until 1855-56, when “The law for the emancipation of all Gypsies”(sic!) was finally passed. Gil emphasizes that the period of Roma slavery in the Romanian principalities lasted around two hundred years longer than that of the transatlantic slave trade, led by western businesspeople. In his work’s description, Gil quotes Mihail Kogălniceanu (!), who, in 1837, wrote: “The Europeans are organizing charities and fighting for the abolition of slavery in America, while in the heart of our own European continent, 400,000 Gypsies (sic!) are held captive, and 200,000 more are victims of barbarity.” Often when the history of Roma people in Romania is discussed in Polish sources, Emil Cioran – our xenophobic scapegoat – is quoted, as is the case in a study published this month, authored by Slawomir Kapralski. To translate: Emil Cioran considered [the Roma] a primitive race of barbarians, while at the same time idolizing them for refusing the fall of eternity into Time and for their rejection of historicity.

A row of ghostly figures – as Weychert-Waluszko calls them – shamble around a few riders. They are draped in black cloaks, which erase all differences of sex, age, features. Gil claims that the work functions like a protest against romanticized and orientalized visual representations which come to replace actual historical events involving Roma people in the collective imagination. Gil claims there is no visual “documentation” of Roma slavery. The Transylvanian Panorama also documents a stereotype and does not record the historical exodus of freed Roma (and other) slaves that took refuge from the country of their former boyar owners in places like Transylvania. The Transylvanian Panorama was commissioned by Hungarian officials, likely with the goal of celebrating heroes, so, implicitly, also to manipulate, to emphasize certain events while avoiding others. But we should also remember that Styka & Co did not fully conform to the commission’s guidelines, which led to a conflict with the patrons and, later, to the Panorama being cut up.

Gil’s figures make us think of certain elements of Holocaust iconography. The heavy wave of emotionally-charged content can be seen as an essence in itself, the weight that Jews have borne throughout the centuries, wandering the world, under the threat of being struck and beaten, of pogroms, of annihilation, something banished from everyday thought but still present and, as we now know, a justified fear. Gil’s images are like rows of Requiems – I am referring here to Lazăr Dubinovschi’s sculpture housed at the Museum of Jewish Communities in Bucharest, representing a draped and seemingly hollow figure. This, in my opinion, explicit visual connection in Gil’s work between the tragedy of the Roma and Jewish peoples, tackled by Romanian artists as well, like in Radu Mihăileanu’s extraordinary film The Train of Life, is all the more interesting considering how Romanian activists committed to the liberation and emancipation of Roma people at the dawn of the modern Romanian state, of exploited peasants and workers, who also extolled “the civilizing role of women,” going so far as to suggest the proto feminist idea of including women in government, and some of whom had gone through the experience of exile, like Cezar Boliac, treated these two large communities very differently. „When the young Romanian capitalism will start to consolidate itself and begin its struggle against foreign capitalism, demanding protectionist policies and leading to xenophobic and chauvinist anxieties, Boliac will be on the same ideological and political line as this bourgeoisie,” writes Papadima. In Leon Volovici’s Nationalism and the “Jewish Question” in Romania in the 1930s, we find some more details, and the xenophobia and conservatism that 19th century Romanian politicians were guilty of are unfortunately still seen, in varying degrees, in most governments of the world, including the member states of the European Union, and the state of Israel, regarding other ethnic groups.

The table of Roma communities that Achim offers in his book is vast and gives some needed context to understand Gil’s painting, for example about the ceaseless exile that Gil speaks of, which was not unidirectional, but highly complex, being influenced by a lot of political and historical factors, as well as about the Roma community’s absence from public interest, including after their legal emancipation. Gil makes us see Transylvania as a buffer zone through which Roma people passed in their difficult journey towards freedom.

Gil is also the author of another large-format work, also in a half-circle display in 2018, Tajsa. Wczoraj i jutro [Yesterday and Tomorrow]. The term tajsa refers to the recent past and future in Romani.[2] The work was presented in the exhibition Witamy w krainie, gdzie Cygan ginie [Welcome to the Land where the Gypsy Dies] (sic!). The title referred to a hate rhyme found on a wall and debated in the Polish blogosphere a few years ago.[3] Tajsa comprised visual quotes from classic European painting, which viewers could easily identify, as they are from famous works – The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp by Rembrandt, Irene leaning over Saint Sebastian’s body from a painting by Georges de la Tour, or various still lifes from the 18th century depicting bodies of hunted animals. The viewers are easily seduced by the drawings’ elegance, which guides them towards what is visible, to the common universe of general European culture. What remains almost invisible is the essence of Tajsa’s composition, situated in the center – the result of a Heidenjachten, a Roma hunt. Gil has placed, in the center of the painting, a human body whose limbs are entangled in the bodies of the hunted animals. It is hard for spectators to notice this detail, as they lack the necessary interpretative tools. I for one did not notice it, as I was also unable to read L.M. Arcade’s Poveste cu Țigani [Gypsy Story] (sic!) or any of the author’s plays.

We are used to seeing only that which is offered us through education: elements of the dominant culture. We overlook what we do not wish to see: the victim or the hunted. For Tajsa, Gil started from a fragment from a German hunting chronicle from the 17th century: “We have shot a beautiful stag, five does, three large boars, nine smaller boars, two Gypsy men, one Gypsy woman, and one Gypsy boy (sic!).” In the 17th century, in what is now Germany and The Netherlands, there was a law that stated one could shoot a Roma person without being held accountable. The practice of hunting Roma people was thus developed. Hunting became a form of public entertainment, and this practice continued into the 19th century. Even though in the Białystok exhibition Gil does not reference Roma people from Western Europe, this earlier work of his can offer us some clues why Roma people in the East chose to remain passive instead of all fleeing from slavery towards the West, and why many Roma people from the West ended up in the Romanian principalities, the so-called netoți. Murdering slaves was, at least, illegal in the Romanian principalities.

Specialists are familiar with the issue of the Roma lăutari’s [lit. fiddler, referring to musicians playing in groups, regardless of instrument – tr.n.] image in European culture. I would defend Styka & Co’s depiction of Roma musicians for two reasons. The first is that they decided to include them in the Transylvanian Panorama. They could have simply omitted them. We know that among the laws passed by Joseph II of the Holy Roman Empire was one that sanctioned Roma lăutari – the law “De Domiciliatione et Regulatione Zinganorum” [Of the Settlement and Regulation of Gypsies] (sic!), passed October 9, 1783. I have my reservations in seeing only colonized symbols in images of lăutari. The characters in Loteanu’s Lăutarii, for example, are highly complex figures that resemble contemporary socially engaged artists, in my understanding of the term. The movie also begins with a scene in which the protagonists talk about how they will be bought, and how they can resist this, by escaping, for example. The story of Lăutarii correlates interestingly with Jewish lăutari of Sholem Aleichem – Stempenyu: A Jewish Novel or Wandering Stars. One can speculate that the lăutari were the most relevant and creative parts of the social fabric, not just guardians of the oral tradition. Undoubtedly, they tried to strengthen the unruly communities of the Roma, as the Jewish lăutari also did. It is no coincidence they were also called zicași [lit. teller – tr.n.].

Białystok used to have a considerable Jewish population. Today, all traces of this community are all but gone. It only survives in some old wooden houses still left standing, which were inhabited, and sometimes also built, by Jews. Nowadays, these houses burn down, are sometimes burned down, and in their place come new buildings, with higher living conditions, but with no memory of the past. In her Spring In The Józef Bem Housing Estate (an installation sharing the exhibition’s name), Diana Lelonek shows a surviving fragment from one of those houses that burned down. She placed it in a display case like a museum exhibit. If their inhabitants were first thrown out of their homes, sent into furnaces, and then erased from urban memory, and if their houses seems to be destined for the fire as well, the least we can do is preserve their ashes, if they can be preserved. Lelonek comments on how short our memory is, a memory that allows us to commit new atrocities, as we know we can just forget and pretend nothing bad ever happened. Not all executioners are plagued by nightmares.

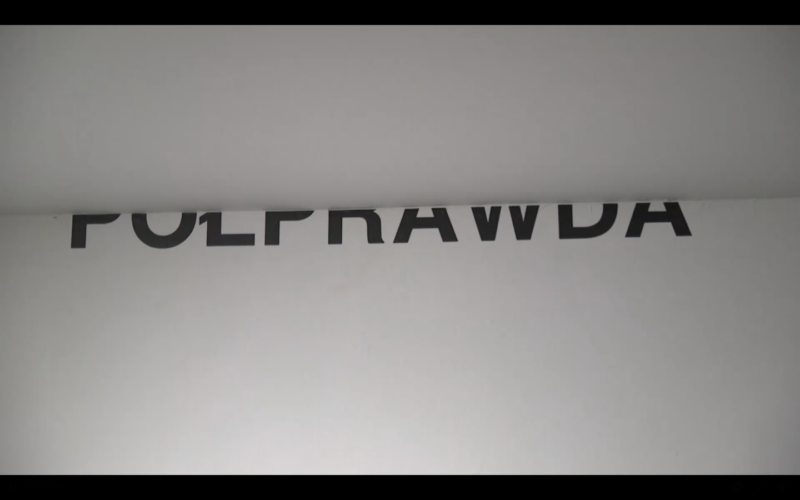

Pravdoliub Ivanov’s Half-Truth – that is how one could translate the Polish original Półprawda, which has been cleaved in half horizontally. It is often that historical events are used as props in the service of ideologies, policies, laws, or the more or less ridiculous private agendas of great and petty oligarchs alike. At the curators’ invitation, Agnieszka Dragon and Agnieszka Dybowska, together with the urban gardeners from the General Zygmunt Berling Community Garden in Białystok, in the vicinity of Bem Street, reconstructed the cut-off tops of the letters from the work Half-Truth using objects found in gardens – apples, gardening tools, flowers.

The connections between the lives of Generals Bem and Berling are also interesting. After the Sikorski-Maiski Pact was signed, Berling became the chief of staff of the 5th Infantry Division, joining the Anders Army, created by Polish prisoners from the USSR in 1943, made up of political dissidents or prisoners. Berlin revolted against the Red Army commanders, for which he was removed from his military position, while Bem fought against the Russians with units that had Russian fighters. Both generals were considered heroes and traitors in different historical circumstances.

Women – The White Traces of History

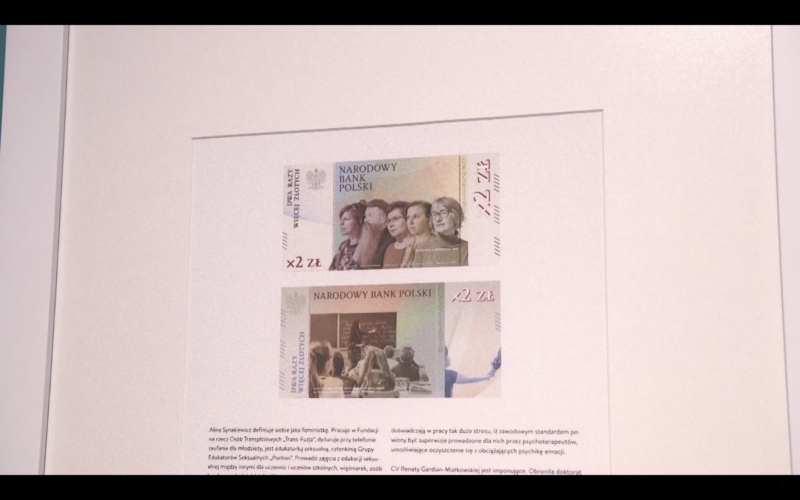

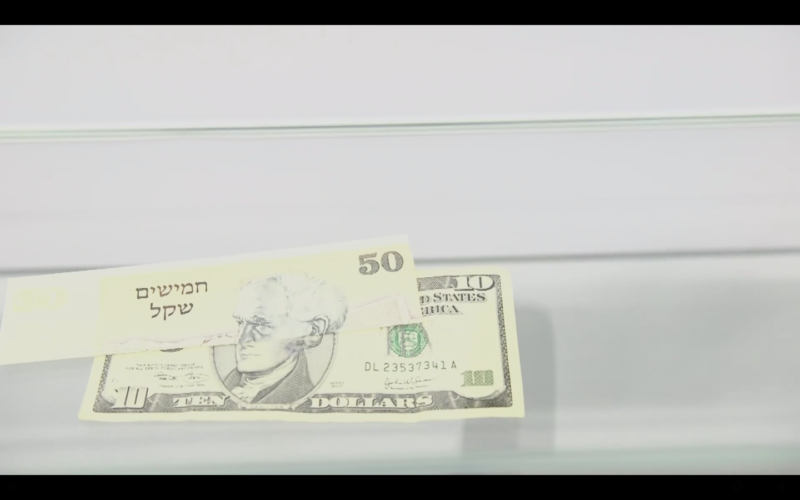

Another interesting patchwork reality transpires from the two collections of banknotes signed by Daniel Rumiancew and Konrad Smoleński. Smoleński’s banknotes bring into discussion the role of the marginals, of people of color, of sexual and religious minorities, and of women in History. I should mention that the central figure in Styka & Co’s taraf is a woman. Smoleński even has improvised Romanian lei. Rumiancew on the other hand tries to highlight the value of regular but invisible labor, from the so-called grey-zone encompassing care work, education, and reproduction, projecting the faces of ordinary people become famous onto the banknotes, among which many portraits of women. Some banknotes are marked with “X 2,” that is, twice the value – suggesting that some professions are insufficiently renumerated – female doctors and teachers. Starting from these works and from the diamonds Boliac “lost,” could someone like Harriet Tubman have existed in Wallachia and Moldova? Unfortunately, I lack the knowledge. They do not teach this in school. I only know about “the famous lăutar Dumitrache – who had obtained freedom from his boyar for 1,000 gold coins, of which 700 were gifted to him by the progressive Câmpianu. […] He would show his gratefulness by playing Boliac’s ‘Marseieza’, which he had transposed into song, at every occasion, for as long as he lived.” It seems music skills could raise the price of a slave, and for good reason. Perhaps it was how the oligarchs of the time recognized talent. I like to think that at least some of them were the mass media of their time, that they cemented an identity of resistance, an identity constructed by actors aware they are being discriminated against, on the opposite position to the majority population, having at their disposal the means to articulate this identity (Castells, The Power of Identity).

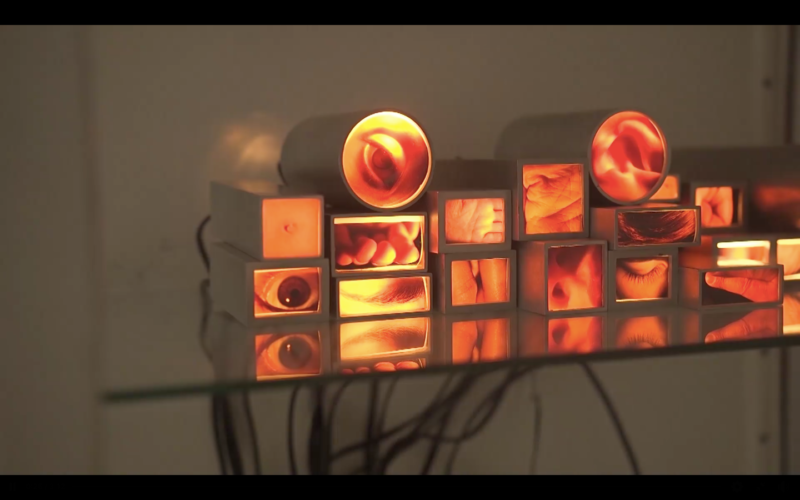

The Springtime of the Peoples entailed, among other things, a shift in women’s roles in the Romanian principalities, which contributed to their emancipation. They became increasingly active in the revolutionary unrest, and some intellectuals began having brazen ideas about allowing them to hold government power. Sometimes women were even reproached for choosing exile instead of actively engaging with the country’s matters (see Papadima). In this light, I would suggest reading Konrad Kuzyszyn’s installation Objects of Being, made in 1999. It comprises a medical cabined on which are placed a few tubes at the end of which, illuminated from the inside, you can see photographed fragments of women’s bodies. We are again faced with the task of reconstructing a totality from which only fragments are available.

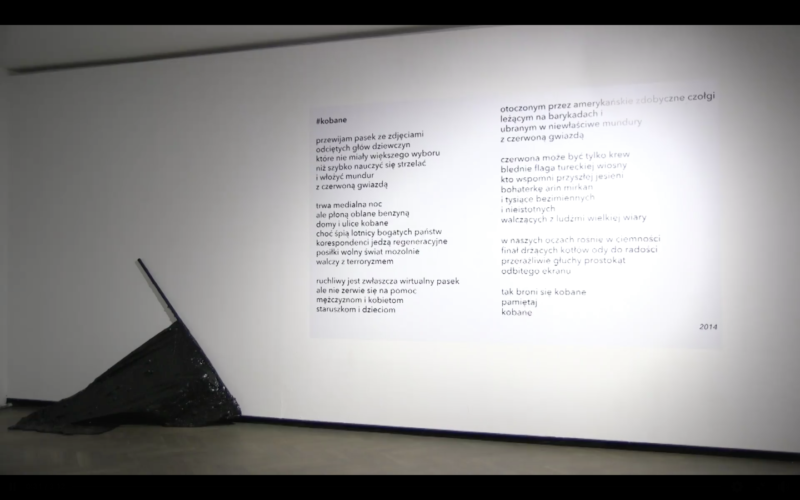

Through his poem #kobane (2014), Szczepan Kopyt, coming from the same direction of war, and of the territories through which Bem once traveled, tackles the viewer’s attempts to reconstruct the feminine subject in History, including the recent one, from which women continue to be excluded, that is, not just overlooked, but destroyed in the most direct and literal sense. The text was also printed on one of Arsenal Gallery’s walls. Kopyt talks about the beginning of the current liberation war in the new Kurdistan, on whose front lines are many female fighters. It is perhaps the most harrowing and difficult to imagine exercise in the whole exhibition –

i’m scrolling down a page of pictures –

decapitated heads of girls

who didn’t have much choice

but to learn quickly how to shoot

and don uniforms

with the red star

Marginal people are redrawn, reincorporated, and reprojected into the eye of history, at least for the duration of the exhibition, at time brought back from their diaphanous coffins. Dorota Podlaska (in collaboration with Marta Skuza and Piotr Matosek) created a work titled The Healed General – Reconstructive Embroidery on a canvas whose frame has the hexagonal shape of a coffin, 187 x 92 cm, and in whose background we see a kind of magnified cellular tissue in warm colors, on which several life-sized images of human bones are minimalistically overlapped – Bem had lost a few limbs during his many battles, but in the end he died of malaria (see Paweł Polit’s exhibition review in Szum Magazine).

Having resurrected all these people and exchanged impressions with them, we get the possibility of offering them closure by saying goodbye to them, to the heroes and their graves. Goodbye is also the title of Martyna Jastrzębska’s series of tarred objects (2014) – crossed crutches, a flag burdened by the black mass, and plane grounded perhaps by the weight of the tar of history. And then, fulfilled and a bit more enlightened, we can continue our journey, as spectators, towards a more or less blinding future. Who knows, perhaps the Transylvanian Panorama will reach Romania too one day, perhaps in a new configuration and with new forces, whatever those might be.

Spring In The Józef Bem Housing Estate

20.06.2020 – 04.09.2020

Galeria Arsenał in Białymstok

Artists: Paweł Baśnik, Przemek Branas, Krzysztof Gil, Andrzej Heidrich, Pravdoliub Ivanov, Martyna Jastrzębska, Nikolay Karabinovych, Szczepan Kopyt, Konrad Kuzyszyn, Diana Lelonek, Dorota Podlaska, Daniel Rumiancew, Konrad Smoleński, Michał Gorstkin-Wywiórski, Tihamér Margitay, Tadeusz Popiel, Zygmunt Rozwadowski, Leopold Schönchen, Béla K. Spányi, Jan Styka, Pál Vágó, Transylvanian Panorama, 1897

Curators: Ewa Łączyńska-Widz, Monika Weychert

[1] Though a 50-meter-long copy was unveiled in 2011 in Sfântu Gheorghe.

[2] See also Monika Weychert-Waluszko’s text “Ucząc się od romskiego Koczowiska” [Learning from the Roma nomads], which also discusses the recent Roma migration from Romania through Poland.

[3] In Polish, “to the land” (“w krainie”) rhymes with “dies” (“ginie”).

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Teodor Ajder

Teodor Ajder was born in Chișinău. He studied psychology at Babeș-Bolyai, Cluj-Napoca, and got his master's degree in education sciences and his doctorate in media, information and environmental sc...

Comments are closed here.