Lia Perjovschi’s most recent exhibition, opened in the space belonging to Galeria Ivan at Atelierele Malmaison, under the intriguing title of Colours. A Deconstructed Painting, calls for a return to color in all its complexity and immateriality, as wavelength, pigment, and affect. After half a life spent constrained by the colors of communism, by shades of gray, after a pandemic in which our everyday was constantly mediated by screens, filters, and RGB codes, the artist’s need to reconnect to the green of leaves, to the blood-red of berries, proves to be a necessary treatment. This operation however is neither simple nor automatically hedonistic. In the age of post prefixes, few still fool themselves into thinking about the so-called return to color as a mere transfusion of optimism or a romantic refuge into nature (for that matter, the only green leaves in the exhibition are present on a piece of cloth cut from a bedding set Lia had purchased from IKEA).

What the artist delivers rather in the context of her series of fragile objects, made of paper or cloth, photos taken from the internet, and tile-sized canvases on which the artist intervenes with ink, color, berry juice, avocado, or coffee, represents a captivating analysis on how affects and colors influence the structure of discourse, be it artistic or political. We also note that Lia Perjovschi’s body of work, whether it be her performances, paintings, installations, and objects or her famous AAC/CAA (Contemporary Art Archive, founded in 1985 / Center for Art Analysis, started in 1999), is structured as a poignant argument supporting the thesis that art, having survived a series of death sentences (from Hegel to Heidegger), cannot survive in the present except as socio-political art. Which does not mean it has lost its transgressive or poetic nature. As Jean-Jacques Gleizal, the author of the famous Art and the Political, stated, “Beuys and the others are poets, and only in this way can they really be sculptors of the social.”

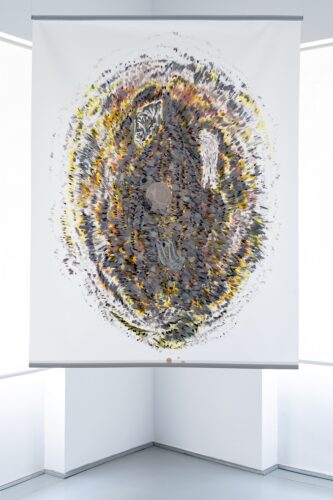

It would therefore be no mistake to say that Lia Perjovschi’s art is poetry. Writing this, two of her tile-sized canvases come to mind. On them, the artist depicts, in a few lines, the black spots that appear in our eyes when we dare to look at the sun, or a surface of light. I also think of her larger work that seems like a solar explosion in shades of yellow and brown that Lia reveals to be the story of a punch: received from potential “parents,” “masters,” childhood bullies, or other people “invested with authority.” Together with this are two small canvases that subtly poke fun at the success of the “Cluj School.” All these works encapsulate feeling and, of course, color, but at the same time, in an exemplary and unexpected fashion, they recover the unconsciousness of metaphysical inspiration given to “Poetry” by the German romantics, Hölderlin’s transgressive courage of performing yourself for the sake of truth, with the risk of losing yourself, Beuys’s later courage of creating your own school if the Academy doesn’t deserve you. In this way, Lia Perjovschi establishes her poetics and socio-political critique, always at the limit of the body and audacity, outside the circles of power and small favors (prizes, studios), creating her own institutions and her own art history curricula when the materials and knowledge are lacking, leaving behind abusive masters and “daddies,” as she conquers distant territories all by herself, biennials and exhibitions whose selections still believe in truth.

We are led to understand that color, for Lia Perjovschi, recovers the purest connotation of political or artistic freedom, satirizing both the flagrant neoliberal encodings of silver, citrus, or magenta commodities, as well as the mimesis of academic art, in concordance with Baudelaire’s inspired call: I want fields tinged with red and trees painted blue! This connection to the cosmopolitan father of Romanticism, modernity, and artificial paradises is no coincidence. Having debuted in the 1980s, within the intersection of neo-expressionism with the “decadent” intermedia waves, Lia Perjovschi integrated into the complex aesthetic tapestry of her projects an opening to processes oriented towards the body, collages of poor materials, democratization and media impact, serialism, and, especially, the expression of raw, authentic experience.

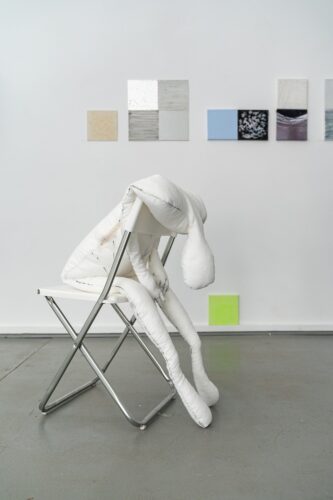

This kind of experience commented on in Baudelaire’s definition according to which poetry and painting express the same thing that emotions, shouts, tears, kisses, and caresses express, in a confused fashion, appears also in Lia Perjovschi’s work, primarily in her older projects: the series of Shadows, 2D silhouettes made of thin fabric, stored on clothes hangers to be work on any occasion like masks, heteronyms, or multiple identities, the series of cardboard and textile sculptures titled Costumes, or the three-dimensional mannequin The Doll, a replica of the artist’s body that does not however show any features or affects on its face. A few precious works from the series Costumes (Impression Maps), fragile casts of the artist’s body with graphic or text interventions, were also included in Perjovschi’s solo show at Art Basel, organized almost at the same time by the same Ivan Gallery. In the Basel exhibition, the Costumes are accompanied by documentations of her performances between 1988 and 1994, focusing also on the body and affect, on connections and discreet communications that reveal the importance Lia places on the relation with the other, with the world and knowledge, as well as on coordinating the individual body with the social one. Also important on this affective map is her personal relation to gallery owner Marian Ivan and curator Diana Ursan, who, with a metaphysical care, have supported Lia’s projects since 2016.

To return to the Malmaison exhibition, the tile-sized canvases displayed in a circle, equidistantly, together with fragments from social media debates, brings into discussion the mechanisms of the archive, its capacity to rewrite history, to settle recent memory, as well as the artist’s duty to act as a mediator of important socio-political events. The pictures on the final wall, dedicated to war and the children who have died in Syria or Ukraine, represent an inevitable return to the palette of grays, to black and white – colors of death in eastern and western cultures. The pictures of these children who cover the eyes of their dolls or raise their arms in fear before the camera mistaken for a gun, lost children (after an accident, within ourselves or in the world), children that we desired but could never had, or that we had but could not love enough, reactivate the archive in the direction of sickness and death (Derrida, Mal d’archive).

The discourse’s circular structure allows however for the possibility (illusory as it may be) of overcoming this wall of pain. Returning to the entrance we discover a shiny pair of 3D glasses, an invitation to explore virtual worlds, the metaverse, which opens before us the latest Society of the Spectacle, new species of simulacra and artificial paradises. Upon closer look, we see a multitude of deliberately artificial colors all around: a sample with carefully codified shades, a citrus-yellow painting placed close to the floor, two boxes with spheres colored in magenta, cyan, and other colors associated with the aesthetics of Vaporwave, NFTs, and other digital evasions.

This marks an unusual bridge between the neo-expressionism practiced during communism, where the infusion of color came from envelopes, stamps, and packaging from the west, pages and advertisements torn from the few foreign magazines that reached Romania, the projects of the ’90s based on xerox technology (applied in the economic and political transition but also in an art-historical recovery), and the media aesthetics centered by Hito Steyerl around the poor image.

In conclusion, the exhibition can be read as a manifesto of freeing color in the neoliberal age of media and digital encodings, in which red, yellow, and orange have become codes of fear, separation, and restriction. In order to oppose media affects, the waves of terror of the media oceans, color and feeling need to be recovered. Together with Lia Perjovschi, we will all free ourselves from EU blue, PNL (the Romanian National Liberal Party) yellow, PSD (the Romanian Social-Democratic Party) red, but also the red of the carnations placed by Putin at nationalist ceremonies that reproduce the “chill” of the Ceaușescu age. We will instead locate our own colors and shades around us, we will recover from the phenomenologists matter as matter, color in itself and for itself, as well as authentic feelings that are difficult to reduce to sets of emoticons or fears triggered in code-orange heat wave warnings or code-red pandemic or storm alerts.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Raluca Oancea

Raluca Oancea (Nestor), member of International Association of Art Critics (AICA) and European Network for Cinema and Media Studies (NECS), is a lecturer at The National University of Arts in Buchares...

www.Dplatform.ro

Comments are closed here.