The social apparatus for excluding women from the production of institutional culture is one that still functions quite well. Let’s say you are a child who thinks that painting and drawing are the most beautiful things in the world. If you are identified as a girl, you are taught that the world’s greatest artworks are made by men. And then when you get to high school and you’re already a “lady”, you are reminded that the gaze for which paintings are made belongs to a heterosexual man. Perhaps you won’t experience this exclusion until later, in college, when you notice that your male colleagues, who always seem to be more artsy than you, are favored by your professors. Or maybe you’ll notice it when you start your job at the art university’s painting department, where you are told that no woman ever got to be a professor there. [1]

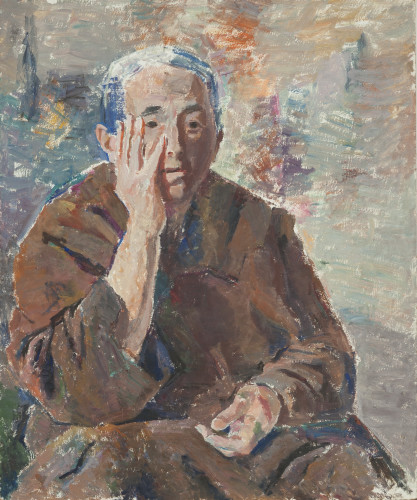

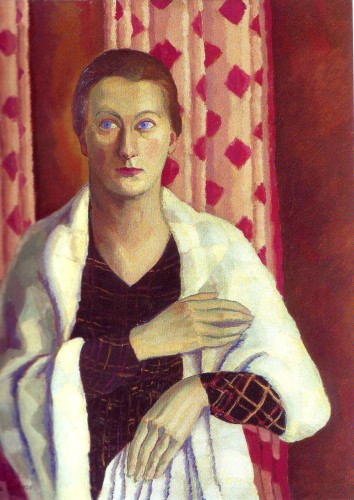

The gaze of the girl who starts to suspect this long series of exclusions should be addressed first and foremost by the exhibition “Equal: Art and feminism in Romania”, on view this spring at the National Museum of Art in Bucharest. And with the perspective of a continuation of that very efficient apparatus of exclusion, let’s contextualize the entire “Equal” project: the art show, the catalog and the connected events. As curator Valentina Iancu puts it, “Equal” is “an effort to historically map modernist female artists that activated in the Bucharest art scene” – women that activated in the art world, as well as manifested an interest in a feminist artist organization. The art show’s nucleus is chronologically placed between 1916 and 1939, a period that Iancu identified as being fundamental for the history of female artist groups. The selection of artworks made by women is considered complementary to “the militant activity for emancipation that they performed”. So, as opposed to the problematic feminist art shows that have the unique criteria of identifying artists as women, this project managed to bring together not just art works produced by women, but art works produced in the context of a political struggle for women’s emancipation. In the current context, the curator is vehemently criticizing the underrepresentation of women in art museums in Romania today (less than 5% of the body of work exhibited was made by female artists).

Going over the exhibition as well as the catalog, one can sense a tension throughout the whole project, giving the project a layer of ambivalence. The text on the wall that greets people who visit the art show talks about the intention of writing a “feminine” local art history, a retracing of modern history by integrating female names. Thus, the known history that is taught in schools – masculine and patriarchal at that – is corrected, adjusted in order to make way for some invisible trajectories. Art produced by women is considered a different kind of addition, a chapter in the dominant historical narrative with the goal of demonstrating that women can and have created art that is worthwhile. But that selection of works denotes the outline of a different kind of route that breaks the logic of women-can-also-do-it. It looks more like the shaping of an alternative universe, with its own logic and aesthetic, doubled by a special kind of organization and solidarity.

The dominating theme of the art show is that of the domestic space, women in an interior environment, with their families in their homes. The figures that are presented are almost exclusively women, with just a single portrait of a man, and the works are accompanied by the story of the political organization of the artists for their professional recognition. This structure shows the subjective, personal reading of the curator. After all, this is not a comfortable addition to the dominant historical narrative, but rather a reference to an alternative history that is not just a mere echo of the dominant direction of male artists’ art. The curator does not investigate a so-called historical truth, she undermines it and “forges” it, creating a counter-narrative that reflects “a personal feminist filter”. We must deal with the shaping of an alternative art world, with its own themes and socio-political dynamics, which represents the typical experiences of women in those times. So, the art show wants to surpass the extremely limited historic paradigm of correcting history by adding women in the mix and suggests a far more radical method of deconstructing the historical narrative. Such a deconstruction is done by interpreting various art worlds as not following in the long line of modernist “-isms”, but rather they create aesthetics and new social logic that reflect the experiences of the authors, thus questioning the very patriarchal foundations of producing the history of art.

Yet, this irreverence towards hegemonic patriarchal historical narratives is not typical of the artists in the exhibition. We are, after all, talking about people who were part of the more privileged classes of those times, privileges built on fortunes, families and institutional racism that operated then – the ongoing anti-Roma racism and anti-Semitic racism in full swing. Most of the artists rally for liberal feminism, a feminist view where – in those times, at least – women who belong in wealthy and renowned groups fight for being acknowledged in the same way as the men within those groups. It is more of a fight for equality within society, and not so much for justice.

The only one in the art show that breaks the pattern of the liberal discourse is Nina Arbore, a standout transversal artist. The little sister of Ecaterina Arbore, a remarkable figure of the socialist movement and left-wing feminism in the Romanian context, she is part of a radical left-wing family of intellectuals that also includes Zamfir Arbore – the father of the two – an influential thinker who took part in the anarchist movement in Eastern Europe. The artist herself is also an important fighter in the left-wing feminist scene and her work, from the curator’s perspective, is complementary to her political work, exhibiting an aesthetic that brings “extra value to the socio-political ideas that defined her personality”[2]. Nina Arbore must be seen, thus, not as representative for a type of art, but for a typology of artistic personality: the engaged artist.

Through the affirmation of the engaged artist type, Arbore breaks the apparent consistency of the exhibition and sheds light on the history of a different type of feminism, a much more radical and democratic one [3]. Socialist and communist feminism – left-wing in short – has a parallel genealogy to liberal feminism. This type of feminism comes from the experiences of industrial and domestic female workers from the underprivileged classes, aiming not only towards “equality”, but also towards a structural change in the conditions of labour and social organization within society. In other words, left-wing feminism was not aiming to feminize the masculine statuses of society, but to radically reorganize society so that women’s experiences be acknowledged and be able to influence governance, labour and the organization of public resources. The women organizations that popped up in the first decades of the 20th century were fighting to end the war, stopping fascism, workers’ rights, fair pay, taking part in governance, children’s protection and education, etc. The 30s were the years of massive general strikes and the explicit antifascist organization among women. Some of the organizations founded in those years were Working Women’s Union (1930), Women’s Antifascist Committee (1934) and The Feminine Front (1936), with Nina Arbore activating in the first and last. These initiatives will have the same fate as the small organizations and committees before them: they will outlawed by Carol the Second’s fascist regime. At the same time, this regime accommodates the structures of bourgeois feminism, further antagonizing the two feminist routes. One should see the art show with women artists organized by the Ministry of Propaganda in 1938 from this perspective – an art show taken as a temporal mark for the Equal project.

For the spectator unfamiliar with feminism’s diversity, “Equal” does not do much to honor this complex history. Unfortunately, it rather strengthens the idea that there is only one type of feminism – liberal, based on fitting in history or society without questioning the basis for exploiting and oppressing patriarchal structures.

Thus, we can ask ourselves: why consider a few very privileged women, that were part of a high class, the predecessors of us all? One possible answer would be not to see them as predecessors, but as women who, at one time, gained something that can be of use to us today. The project “Equal” offers to the general audience the idea of a model for organizing and concrete transformation of the social apparatus for excluding women in the visual arts field. It is a good model for organizing based of solidarity, yes. But not just solidarity based on gender, but also one based on privileges. And, it is not just that this is not enough, but in today’s context, it should be condemned from the start. More than just revealing a historical pattern for a feminist political organization, the project talks about attacking the places where patriarchal hegemony is reproduced together with class and race privileges. In universities and museums, where canonical knowledge is produced and reproduced – all these should be seen as a battlefield and not spaces of retreat and safety. This way, we see the relevance of the curator’s historiographic method and Nina Arbore’s artist typology.

The patriarchal mechanisms of reproducing canonical culture must be questioned, provoked and stopped from a necessarily transversal, anti-racist and anti-classist perspective. And marginal subjectivities are never safe within the spaces where the cannon lives in. So, maybe the greatest merit of the women artists from this art show is that they began outlining a parallel history, they put up a few bricks – even though their basis was their own privileges from class and race – in the scaffolding of a siege against the canon itself, an attack that manages to hit only after the play “Del Duma. Talk to them about me” was performed in the halls of the Museum of Art, as a connected event.

In contrast to the peace and safety surrounding the characters in the exhibited works, we get to listen to stories of Roma women interpreted by Mihaela Drăgan: stories filled with anger and solidarity, dignity and nerve – affects and attitudes that are the marks of oppression and not privilege. It is only through the words of Mihaela, Maria, Calofira and Roxana in “Del Duma”, that “Equal” becomes coherent as an act of denouncement – via sisterhood – of the spaces where the canon is reproduced and an act of claiming the art field as battlefield and not a place of leisure and safety.

[1] Episod real care a stat la baza cercetării și intervenției „Arborele sub care am crescut”, 2012.

[2] Valentina Iancu, “Equal. Art and feminism in modern Romania”, the exhibition’s art catalogue, Vellant, 2015, p. 50.

[3] See Elena Georgescu and Titu Georgescu, “The democratic and revolutionary movement of women in Romania”, Scrisul Românesc, 1975 and Luciana M. Jinga, “Gender and Representation in Communist Romania. 1944-1989”, Polirom, 2015.

“EQUAL. Art and Feminism in Modern Romania” is between 17 December 2015 – 17 April 2016 at the National Museum of Art of Romania.

The curator of the exhibition is Valentina Iancu, a specialist in the Section of Modern Romanian Art of the National Museum of Art of Romania.

POSTED BY

Veda Popovici

Veda Popovici (b. 1986, Timisoara, Romania) works as a political artist, engaged theorist and local activist. Her interests include identity representations in art, intelectual genealogies of power, c...

veda-popovici.blogspot.ro/

Comments are closed here.