#74-75 A Segment of Romanian Artists Originating from Romania

2025

The print magazine comes out three times a year with double issues starting with 2010.

It is available in bookshops around the country such as Cărturești, Humanitas, Librarium, Alexandria, P U N C H; at Dispozitiv Books (Bucharest), La Două Bufnițe (Timișoara), Kyralina (Bucharest) and Quadro Shop (Cluj); in Relay and Inmedio newsstands; in partner galleries such as Galeria Posibilă and Mobius Gallery in Bucharest; from our editorial office, as well as in UAP local headquarters.

By clicking on the title of each magazine below, you can buy individual issues either as digital content or in print format.

For orders outside the EU please email us.

Annual print subscriptions for our readers in Romania and the Republic of Moldova cost 110 RON (24 Euro).

Annual print subscriptions for our readers in the EU cost 160 RON (33 Euro).

The current dossier is dedicated to the International Association of Art Critics (AICA), the most prestigious global organization in the field, founded in 1950 and affiliated with UNESCO, as well as to the positive influences brought about by Romania’s accession to this structure beginning in 1966.

“The Romanian Union of Fine Arts Awards are an excellent annual occasion for a collegial evaluation of the artistic activity and cultural production of the previous year. It is an opportunity to identify and reward both the performance and the involvement of artists in the Union’s social and cultural life.

Our attention is focused on all types of expression in the field of visual arts, but also on art critique, specialized literature, including art history, research and curatorship. We also intend to map the remarkable artistic productions in Bucharest, which is a strong scene with a spectacular dynamic of events, but also in the region, where we have noticed an effervescence worthy of interest. In this context we have to mention Timișoara, a city that has become a great cultural center, of course also helped by the happy context of its designation as European Capital of Culture in 2023. The frequency of cultural events has increased all over the country and the interest of artists to create visibility and imagery, I believe, or at least I hope, that it has also been stimulated by the projects that the Union of Fine Arts has been promoting regularly in recent years through Annuals, Biennales, the National Contemporary Art Salon, the Romanian Union of Fine Arts Awards, etc.”

Petru Lucaci, President of the UAPR.

Today, we find ourselves in the same pedagogical impasse – the continuous need for curricula, course materials and lesson plans to legitimize and validate education, even though they are merely normative acts and a bureaucratic way of teaching, which turns us and a large part of the educators into mere functionaries of different subjects. It performs an education whose merits come only from grades, marks, Olympic medals, and standardized tests, because otherwise, most of our society consider it inadequate and adrift.

This Arta dossier dedicated to education, appears thanks to the invitation addressed by Marina Oprea, together with Gabriela Mateescu, and encompasses the majority of the dilemmas we have faced throughout our journey as artist-educators: from the need for certainties that give meaning to our efforts, to the necessity of relating to current theoretical frameworks; from knowing the historical context to understanding the contemporary one; from the idea of educational spaces to the idea of safe and inclusive learning spaces; from being stuck in the narrative of “alternative” and “non-formal” workshops, to the need for long-term programs; from the fear of education suspended between ”edutainment” and “pedagogical aesthetics”, to the hope that art still has the ability to invent “mutant coordinates” and generate “unprecedented qualities of being”

Laura Borotea & Gabriel Boldiș (Minitremu)

“During the last decades, Moldova has undergone significant changes in various realms of life, including politics, economy and the social and cultural domain. The country has gone through a global transformation: the transition from Soviet socialism to neoliberal capitalism, from a centralized economy to a market economy, from a socialist organized society to a consumer society. The process of this transition period, along with the democratization of public life, was interspersed with economic crises, political tensions and social problems. In such an unstable and rapidly changing environment, artistic life also experienced changes and transformations. The liberalization and decentralization of the arts sector in the late 1980s and early 1990s encouraged the development of cultural centers, alternative platforms for exhibitions, both commercial and non-commercial, and a number of other initiatives. It has expanded the ability of artists to express their ideas, creative approaches and the diversity of artistic practices. After the collapse of the USSR, in Moldova, as in the entire post-Soviet space, the Western influence began to strengthen, which gave birth to new trends and directions in art. New cultural actors have appeared: curators, managers, gallery owners, those who have transformed and are actively transforming the artistic environment in the last three decades, thanks to whom we observe the diversity of artistic expressions and the freedom to create outside of traditional institutional frameworks. (…)

The current dossier of ARTA Magazine contains documents and testimonies that reflect the process of forming a democratic society in the Republic of Moldova through the active influence of artists, cultural workers and activists as agents of change and transformation.”

Tatiana Fiodorova-Lefter

“As always in recent years, issue 64-65, the third issue in 2023 of ARTA magazine, is dedicated to several major collective programs of the Romanian Fine Artists Union. The main dossier of the issue includes texts and images about SNAC – The National Salon of Contemporary Arts. Now in its sixth annual edition in its post-1989 formula, and thus resumed in 2018, SNAC 2023 is placed under the general thematic banner of ‘Survival’ in these troubled and tense times. With over 300 visual artists from all over the country, SNAC took place in 9 art galleries and 3 partner museums in Bucharest.

The second thematic dossier of this issue is dedicated to the 2023 UAP Awards. UAP’s priority project, like SNAC, which has also been running continuously for several years, the UAP Awards – 19 in number – were awarded to the following disciplines: painting, sculpture, graphics, design, multimedia, decorative arts, scenography, diaspora, art critique, youth, religious art, art in the public space, excellence, ARTA magazine, the UAP Board of Directors, the Jury, the AVV Foundation, Ion Atanasiu Delamare, and last but not least, the grand prize. Detailed presentations of the winners can be found in the pages of the magazine.”

Magda Cârneci

The European Capital of Culture (ECOC) is a European Union initiative launched in 1985, with the title awarded to cities in the Member States on a rotating basis each year. Timișoara is not the first such Romanian “capital”, after Sibiu, in 2007, coincidentally also the year of Romania’s accession to the Union, first tested the waters of such a project.

Probably not many would have expected to find in Timișoara – and only in the first half of the year – paintings and drawings by Adrian Ghenie, gathered in the exhibition “The Impossible Body” organized by Art Encounters, about which Maria Orosan Telea writes; by Ioana Bătrânu and Adela Giurgiu, also at AE, in a film-visual dialogue with Agnès Varda, written about by Raluca Oancea; contemporary art as in “Different degrees of freedom”, at the Kunsthalle, reviewed by Horațiu Lipot, or as in “On the generation of generative forms”, about which Bogdan Ghiu writes; or even more Romanian contemporary art, as in “GAME ON”, an exhibition based on the idea of competition, recounted by Ada Muntean; the late Mircea Nicolae and the small and precious things, about which Elvira Lupșa writes so nostalgically; Irina Gheorghe’s experimental performance, part of the “New Times” exhibition, reviewed by Gavril Pop; and, last but not least, “The Sculpture after Sculpture” at Cazarma U, a feast of volumes in space, about which Corina Șuteu writes with great admiration.

“The dossier of this issue of ARTA magazine is structured around the painter Hedda Sterne. Born in 1910 in Bucharest, active at a very young age in the Romanian avant-garde movement, alongside Victor Brauner, Marcel Iancu, and M.H. Maxy, introduced to the French surrealism of the 1930s, but settling in New York in 1941, where she discovered abstract expressionism and abstractionism, Hedda Sterne is a fascinating personality who deserves being introduced in the international modernist canon.”

Magda Cârneci

The 59th edition of the Venice Biennale (23 April – 27 November 2022) stands under the sign of “The Milk of Dreams” proposed by curator Cecilia Alemani, following surrealist artist Leonora Carrington (1917-2011). A biennial that has been postponed one year due to the pandemic, a rigorous research-biennial that focuses on the history of 20th century art more so than in the past. For the curator, it is vital to revisit the historical avant-gardes, but in a different way from what we are used to: this edition of the biennale belongs exclusively to avant-garde women artists, whose discourses find themselves relevant, fresh, present in the tissue of contemporary art. In Venice, the avant-gardes become bridges not only with the present but also – something you notice as you visit the exhibition spaces – with the future. We appear to be witnessing a unique time, a time of perfectly contemporary historical compositions that impeccably anticipate the future.

The 52-53 issue of Revista ARTA proposes a foray into the history of the 100 years of professional organization of visual artists in Romania, from the Fine Arts Union of 1921 to the Union of Visual Artists of today – a long period, marked by many political changes and radical, social or economic problems. The guild of visual arts professionals has not only brilliantly survived but continues to produce major exhibition events within the contemporary art scene, events discussed in the pages of this issue. The National Salon of Contemporary Art, the U.A.P. Awards Gala, the dozens of domestic and international exhibitions recorded in the gallery’s diary are just a few examples of events produced or supported by the organization now known as the Union of Visual Artists in Romania.

Issue coordinated by Petru Lucaci

This dossier proposes an investigation on the way in which concepts such as memory, archive, and database are approached in the visual arts, in the context of the important recent changes like the dismissal of linear narratives, dissolution of gender, proliferation of interdisciplinarity and inter-mediality. In addition, the research will also probe the interferences between the role of the archivist artist and that of the historian, anthropologist, and collection curator. Our contribution – inevitably, a partial one – to this extremely wide topic debate will look at questions such as: What does the archive, as a form or medium, mean? What kind of gaze does the memory engage? How do acts of memory and archived items gain an educational, anthropological, or historical meaning? What is the often-mentioned transformation of “documents into monuments” (Foucault)?

Coordinators: Horea Avram & Raluca Oancea

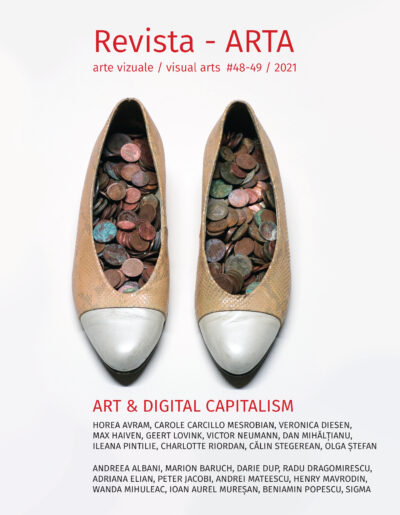

Even if today many of the theories and claims formulated in the Communist Manifesto and Capital have materialized, have become the norm or are understood as necessary in most developed democracies, without necessarily undergoing a proletarian revolution, exploitation, inequity and exclusion, however, are gaining other dimensions, entering the digital globally controlled world by the internet giants, the “Agents of digital capitalism”. Digital Capitalism, a term widely circulated today and analyzed in various publications by a number of authors, not only represent projection of current theoretical positions and philosophical ideas, but also a reality that requires an approach and a deep understanding. The articles included in this issue of the magazine attempt to analyze this theme from an “artistic perspective”.

(Dan Mihălțianu)

“The two coordinators of the file, art historian and professor Ruxandra Demetrescu and curator Diana Marincu, invited a series of Romanian and international theorists and curators to discuss the role of the curator today, in close connection with the exceptional situation created by the global pandemic. Some of these texts are an absolute novelty, and some authors were translated into Romanian for the first time on this occasion. The magazine’s content was also adapted on the fly and the traditional sections were dropped in order to make room for Romanian artists to show us how they faced this unprecedented situation. 17 artists answered: Silvia Amancei & Bogdan Armanu, Sandor Bartha, Liliana Basarab, Anca Benera & Arnold Estefan, Răzvan Boar, Alex Bodea, Răzvan Botiș, Roberta Curcă, Lucian Indrei, Lera Kelemen, Aurora Kiraly, Ciprian Mureșan, Lea Rasovszky, Ioana Stanca, Miki Velciov. In addition, 7 art spaces from Bucharest and across the country presented the projects they initiated for this emergency situation.” (Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-chief)

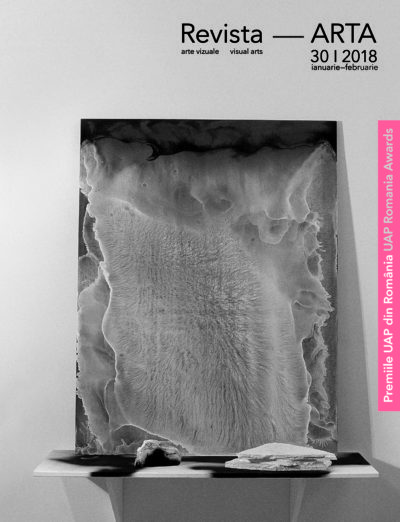

”The Romanian Artists’ Union Awards 2018 showcase the year’s visual arts achievements in all their diversity. The award also aims to consolidate the collaborative tradition we have had with the Ministry of Culture, which can ensure the continuity of the project and, we hope, its expansion, including it into the larger scheme of an international art salon with awards, grants for young artists, and the selling of works for state collections, following the model of the interwar Official Salons.” Petru Lucaci

The magazine also includes two interviews with Cătălin Bălescu and Mihai Zgondoiu, numerous reviews of Romanian exhibitions such as “24 arguments” at MNAR, “Mattis-Teutsch” at Scena9 Bucharest Residence, “Iulian Mereuță” at MNAC, a wide range of reviews for international exhibitions including “Victor Brauner” exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, “Brâncuși” at BOZAR Brussels, “La Fondazione Roma”, “Tim Walker” at Victoria and Albert Museum London and the mapping of some of the most recent cultural events in Romania.

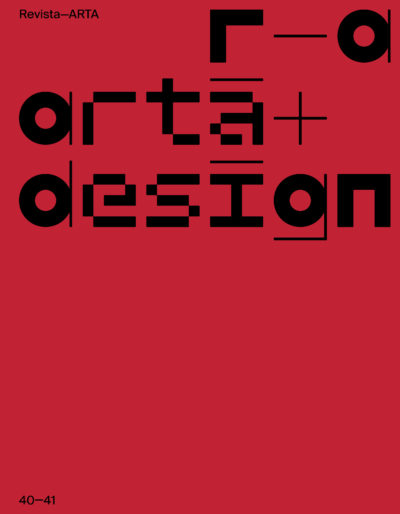

“There is a beautiful structural similarity between the Art-Design relationship and the double helix of our DNA; a paradoxical evolution that unfolded in parallel and simultaneously in interdependence; a synthesis dynamics in which we can see elements that come into contact, are combined and are united by bridges, thus forming new complex structures. There is the assembly stage or the Fusion moment. Subsequently, there is a process of dispersion, when the elements get further away from one another, seemingly needing recoil to analyze the result or the newly created bigger picture. There is the Diffusion stage, a particle flux, a gradual mixture and homogenization; then, the passage to another level. The environment of creativity and ideas, obviously fluid, is also the environment in which design is developed, where, exactly like a chemical mixture, links are being done and undone through affinities and exchange of energy values between parties.”

Gabriel Decebal Cojoc

In the hopes of making available to the general public a dense and structured information about this quite recent field in Romania, the design file aims to outline the local history of this profession at the intersection of technology with art and mass production, as well as draw the vectors of innovation and creativity of the new generation of young designers. Last but not least, the file documents the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the design department at the University of Arts in Bucharest, comments on the retrospective exhibition organized on this occasion at MNAR, and pays tribute to some important figures from this area such as Paul Bortnovschi, Norocel Constantinescu, Ion Bițan and Vladimir Şetran, Alexandru Călinescu-Arghira, Marcel Klamer, Radu Teodorescu and more.

We would like to thank all of our collaborators for authoring the extremely stimulating texts present in this issue: Ioana Avram, Răzvan Boar, Cătălin Boto, Gabriel Decebal Cojoc, Radu Comșa, Monica Crânganu, Mirela Duculescu, Adrian Guță, Lucian Hrisav, Mălina Ionescu, Miriam L. Leonardi, Horațiu Lipot, Elvira Lupșa, Ioana Marșic, Adina Mocanu, Cristian Nae, Ramona Novicov, Dieter Penteliuc-Cotoșman, Gabriela Robeci, Cristina Russu, Cristina Sabău, Simona Stanciu, Călin Stegerean, Bogdan Teodorescu, Radu Teodorescu, Anne-Lou Vicente, Maria Zinz.

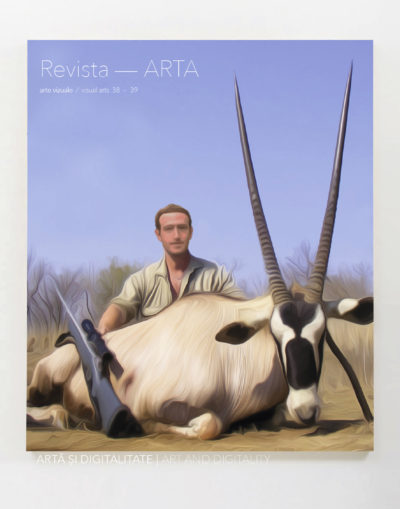

We are traversing some interesting times in which even the confabulatory acumens of science or fiction cannot keep up with the wondrous effects machines employ towards modulating our sense of reality. The political, social and aesthetic regimes they install superseded our ways of thinking about them. They impair the power we need to muster in order to reorient machines from their co-option from capital towards less compromised ideals. It is as if we are under a permanent state of anaesthesia, spellbound by either awe or horror. Even worse, sometimes our fascination with what we perceive as utterly complex, inventive tech witcheries makes us casually skip the fact that they are also being part or instruments for the further dissemination of inequality and exploitation. Bias and prejudice make their way even there, in the apparently neutral and unpeturberd sequences of code. Benjamin Bratton pointed to this fact, that we submit rather shamelessly to a fantasy of permanent innovation and unlimited intelligence “with prejudice toward disenchantment and without deference for superstition and sentimentality. Other alternatives suggest instead worlds of shit and pain” (The Stack, MIT Press, 2015). An equally escapist faith could be traced down in the way we expect art to behave around our deeply technological times. And, at times, we might feel let down by the fact that theorists and artists alike often chose to paint a rather disheartening picture for our future around machines: “In the muck of symbolic interchangeability (art into money into toy into energy into symbol into .JPG into art into money), the building project needing donors is a new structure that can give rhythm and shape to the global noise. Its gambit embarks headlong into the banality of the universal so as to find the coordinates of eclipse, and the recognition that the end of this world does not mean the end of worlds, but rather of us, which may be our only means of survival. Humans: we come and go.” (Idem)

But why would such conversation be opened here, in Bucharest? After all, Bucharest is not known, at this precise moment of speaking, for being one of those digitally shaped hyperbolic geographies proper to London, Shenzhen or San Francisco? This is not a space laden with promiscuous layers of tech-magic although one is yet to measure how powerful and deep the influence of algorithm-driven decisions from the aforementioned mega centres goes on peripheral spaces like Eastern Europe or the rest of the world which is not a ‘first’. As art practitioners based here in Romania, and profiting loads from the digital divide, we tried to bridge, for the purpose of knowing, how these remote geographies interact. We are delighted to feature some of the most interesting Romanian artists that engage with the topic of technology, while also opening up and paying attention to the international context.

Georgiana Cojocaru

Coordinator of the issue

The Tandem France-Romania

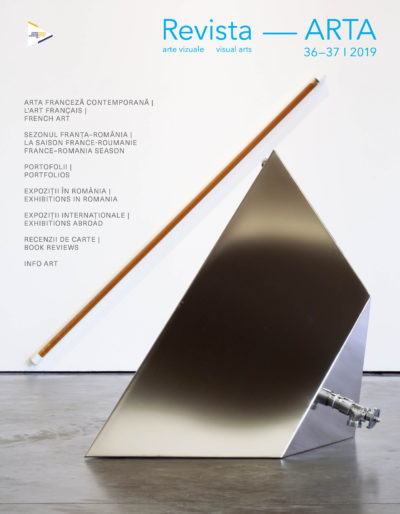

Is it still possible to compile a dossier, inevitably within a limited number of pages, on the contemporary art scene of such a complex and active, not to say ambitious, cultural space as it is the case with France? A space that functions fully on the state of “cultural exception” which turns art production into an important vehicle of France’s European and international strength?

In a world with globalized aesthetic tendencies, could it still be timely to try and define, even briefly, the profiles of artists, groups and movements that could highlight a tendency, a local specificity, one that would bring added value to the universal market of national cultures?

We believe so. Especially when referring to a country such as France, towards which we, Romanians, exercised an enduring cultural fascination. We believe it is worthwhile, at least once in a couple of decades, to put together useful if not relevant information on several artists, groups or visual phenomena that could hint from the smaller scale, specific to the format of an art magazine, that which is happening on a much wider scale – things that give consistency and ground to France’s current cultural strength.

In our dossier, you will find texts about artists such as Pierre Huyghe or Marc Desgrandchamps, about groups known as Supports/Surfaces, about powerful artists such as Tania Mouraud, Apolonia Sokol or Sophie Zenon, about artists who are building themselves a name such as Julien Previeux, Giroud et Siboni, Katinca Bock and Marie Voignier or emerging artists; you will also find interviews with critics, gallerists, exhibitions and book reviews, texts about new trends, and on the progressive return to painting and the figurative after decades in which French art suffered from the “terror of displaying the slightest national feature” (Catherine Millet).

For sure, our intention was to host within our own pages, articles devoted to established artists such as Bertrand Lavier, Bernard Venet, Gloria Friedmann, Eric Rondepierre, Jean-Pierre Raynaud, Vincent Bioulès, Simon Hantai, François Morellet, Bernard Dufour, Gilles Barbier; we would have liked to submit cameos of a number of famous women artists such as Sophie Calle, Annette Messager, Tatiana Trouvé or Camille Henrot; we wanted to be in possession of more information on photography and video. Limited space and other constraints have conditioned our selections, but I think what you will most definitely find in the following pages is a significant sample of today’s visual production in France, too rich and diverse to become easily estimated.

A considerable part of the magazine is dedicated to the exhibitions of Romanian artists in France within the generous format enabled by the Franco-Romanian Season lasting from November to July 2019. What emerges from this selection is the emphasis placed on the experimental, avant-garde dimension of a series of Romanian artists – starting with Brâncuşi to Victor Brauner, to Ion Grigorescu, Geta Brătescu or Ana Lupaş and arriving at the likes of Dan Perjovschi or Mircea Cantor – all of whom challenged and innovated French and Western modernity throughout the 20th century and to this day.

Compiled in tandem with the artpress magazine in Paris, which, in its turn, devoted a dossier on Romanian visual arts in its February issue, this present issue of ARTA magazine took shape during the France-Romania Season 2019 and benefited from the generous support of the French Institute in Bucharest. We take this occasion to express our gratitude.

Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-chief

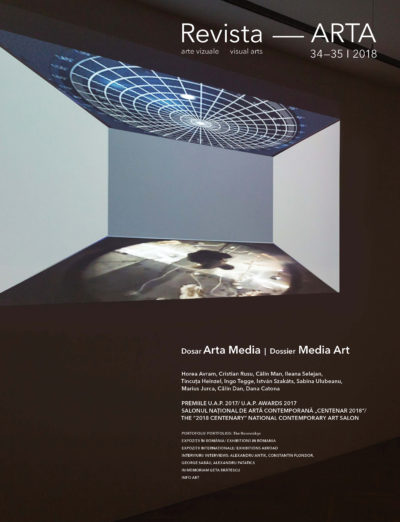

Ideo-mapping: A few reference points about media art

The first difficulty when talking about media art is related to the name itself. What kind of discourse or artistic expression does it stand for? What kind of approach and direction does it embody? Is it related to a time period, or to any particular cultural area? What we know for sure is that media art has stayed with us for decades (some trace it as far back as to a hundred years ago), that books are being written and exhibitions are being made in its name, and that there are specializations and departments in universities devoted to it. We also know that under its semantic arch (sometimes in a bulk), numerous endeavours are carried such as: experimental films, video art, multimedia installations, interactive systems, digital image processing, internet art, sound experiments, mobile devices and applications, Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, video-mapping, social media, CD-Rom, crowd-sourcing and open source applications, ubiquitous computing, the Internet of Things etc. But who can provide an easy and brief explanation on what media art actually is? In St. Augustine’s words, when being asked how can we define time: “if no one addressed this question to me, then I would know what time is”. That’s how things look like in this case as well. And yet, even if it is difficult to capture it in an easy-to-follow definition, one can infer some defining landmarks of media art, which usually boil down to three aspects: the relationship with the so-called mainstream art (the art of major institutions and exhibitions), the medium specificity (following the pathlines opened by modernism) and the role of the digital (sometimes considered a sine qua non/requisite in the definition of media art).

Horea Avram, Coordinator of the special feature

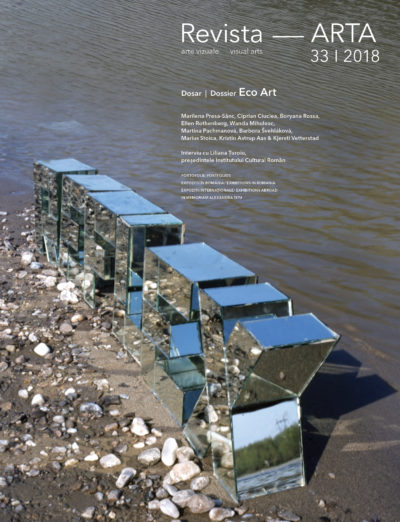

The multiple modern democracies are riding herd, between political correctness and more theoretical efforts of ethical universalism, on a topsy-turvy world marked by the presence of armed confrontations, hybrid wars for territories, markets, oil, etc., delivering geo-political histories full of suffering for both man and the life of the planet.

In the rush for immediate prosperity, one forgets that the Earth, as a living organism, has a limited degree of endurance, and that the wounds we cause it can end up destroying us and the world we live in.

I believe that this state of affairs has helped diversify the concepts and artistic practices originally stemming from Land Art. The aesthetic, introverted, or demiurgic dimension in the relationship between artist and nature and reflected in the 1960s and 1970s environments has become increasingly participative-militant, centered on lived-and-relational aesthetics in contemporary art. Over the past two decades, many critical studies, performative actions, site-specific urban installations made with natural and recyclable materials, abandoned industrial spaces turned into green cultural areas, media works and transdisciplinary exhibitions have been aimed at raising awareness, education and action to protect the environment and quality of life in the globalized digital age.

In this vein, a visionary, complex, and emblematic event was held in Karlsruhe in 2015 at the ZKM (Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie). I am talking about the Globale project, a concept by Peter Weibel, which included a series of exhibitions whose themes analyzed the effects of globalization in the digital era and presented, from an anthropological and geo-political perspective, the histories of humanity in the process of forging a new identity, more responsible for the fate of the planet.

Hybrid groups of artists, scientists and sociologists, carry out in situ or virtual multimedia projects, engage in debates, think holistically starting from heuristically possible assumptions in search of models of living and cohabiting with reality in a postcolonial and posthuman future.

Eco-Art, in this context, blends forms of art, generates attitudes, a constructive way of thinking, of imagining a world. It provides a home for the living.

Text by Marilena Preda-Sânc

Translated by Roxana Ghiță

It goes without saying that the present dossier included in this issue of Revista ARTA cannot and does not aim for an entire coverage of the vast phenomenon of mail art in Romania, a phenomenon that has been going on for several decades (from around the mid-70s up to the present moment). The movement included hundreds of mail artists active on a national and international level who have produced and posted hundreds and thousands of works and postages in a network that virtually covered the whole world connected to the international mailing system. As the mail art practice is founded upon contacts and direct individual exchanges between authors and, simultaneously, on the dialogue established with institutions and independent initiatives (that materialised into projects, exhibitions, publications and archives) it is easy to imagine the amplitude of this network but harder to recover and return its integral dimension. This could act as an invitation to further parallel research and initiatives to fill all the pieces of the puzzle on a truer scale.

Dan Mihălțianu, coordinator of the issue

The 2017 Venice Art Biennale: Beyond Viva Arte Viva

Daria Ghiu

What lies beyond this Long live art/ Viva Arte Viva exhortation? How far can art’s boundaries expand when the viewer gets the feeling that any work of art present in the Biennale’s exhibition can easily be replaced by another work from one’s own memory?In other words, the extremely broad curatorial direction, the hyper didactic tone behind the subsections of the exhibition – what do they say about the status of contemporary art in 2017?.What stays with us after this edition? At its 57th edition the Biennial is strongly marked by the presence of women artists in many pavilions: Rachel Maclean (Scotland), Geta Bratescu (Romania), Tracey Moffat (Australia), Kirstine Roepstorff (Denmark), Lisa Reihana (New Zealand) or Anne Imhof, (winner of the Golden Lion for her performance project, Faust, in the German Pavilion) to name a few.

In the following pages, you are invited to read a dossier about the latest edition of the Venice Biennale. The first article belongs to Cristian Iftode, associate professor at the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Bucharest. In it, Cristian aims to critically analyze and dissect the opening message advanced by Christine Macel for the central exhibition Viva Arte Viva, a curatorial discourse that is superficially engages instruments of philosophy, in an attempt to appropriate a Deleuzian heritage in its main dictum – art as an act of resistance. The second article, signed by art historian Denise Parizek, takes another cut in understanding last year’s biennial: in her analysis, she deals with the artistic positioning of certain provocative artists. These are Phyllidia Barlow, Geta Bratescu, Brigitte Kowanz, Tracey Moffat and Senga Nengudi. Art critic and curator Eleonora Farina makes a case study out of Romania and Italy, as they mirror each other in both the central exhibition and in the national pavilions.

In the second part of the dossier I interviewed Magda Radu, art historian and curator of the Apparitions exhibition, by artist Geta Bratescu, in the Giardini Romanian Pavilion. We tried to achieve a double contextualization: first, what could such a national representation mean in the context of the biennial and what does the strong participation of female artists in solo exhibitions mean within national pavilions? What were the reactions of the international art scene? Then we tried to draw the artistic directions of Geta Bratescu’s work and define the different hypostases of her visual discourse under the sign of “apparitions”. Beatrice Boban comes with an insider view from the Biennial, following her experience as gallery custodian in the Romanian Pavilion. The dossier concludes with an essay by writer Achim Wamssler, centered around Memory, a monumental, yet minimalist work by Geta Bratescu, which occupies one of the walls of the Romanian Pavilion: a reflection on the folds of memory and the “remembered life”.

And so, we present this dossier on last year’s Biennial and Central Exhibition – one that critics have not hesitated to call picturesque and comfortable, rooted in safe, apolitical grounds – but also about the positions of the Biennale’s artists, in several national pavilions, and the artistic force of Geta Bratescu. See you in less than two years at the 58th Venice Biennial.

Translated by Marina Oprea.

Sorin Oncu. Queer Art in Romania

Valentina Iancu

The news of Sorin Oncu’s death at the end of July 2016 came suddenly, shockingly and without explanation. The artist spent his last days at Timișoara County Hospital, where he had been hospitalized with a suspicion of an infection in the body, which has remained, up to this day, unidentified. He was healthy, admitted into hospital care with a minor problem and he died in less than 10 days. Soon after, Cristina Bogdan invited me to write an article about him for Arta magazine’s online version. I realized that I had a first and big blockage in writing a specialized, reasoned and equidistant text, as Sorin Oncu’s more than 10-year work required.

Our collaboration started within the ACCEPT organization, close to the beginning of my curatorial activity, and developed into a very solid intellectual friendship. We intersected ourselves in the context of organizing SilenceKills exhibition, which we jointly curated with Simona Vilău in 2011, a group project that X-rayed by artistic means the most common ways Romanians discriminate. Back then the contact with Sorin Oncu’s work has been very enlightening since our theoretical and political interests were complementary. Sorin Oncu brought to light, through his art, marginal discourses, grave social problems, treated as invisible by the majority.

Being part of a minority, both by belonging to the LGBT community and especially by the condition of “a foreigner” (Serbian) permanently forced to justify his residence in Romania in order to obtain a residence permit here, Sorin Oncu used the filter of personal experience in the construction of a critical art, which poetically questioned society’s limits. Starting from a global understanding of the world in general, Sorin Oncu’s art ”displaces the exclusive focus on the idea of Europe as the cradle of humanism, motivated by a form of universalism that endows it with a unique sense of historical purpose.” 1 The egalitarian utopias widely present in the European Union and the United States of America are in sharp contrast to the discriminatory realities in which the LGBT minority lives, for example.

Sorin Oncu analyzed the migrant’s condition, seen from the position of the Serb citizen who was struggling to obtain citizenship in an EU country, Romania (he failed, despite being born in a family of ethnic Romanians in the Serbian Banat). The last project of the YU-Ro series was completed with the help of Cosmin Haiaş and exhibited at the Calina Gallery in September 2016, after Sorin’s death. The projects of the YU-RO series question the junction and opposites engraved by ethnicity and nation in one’s personal identity. The works exhibited at the Calina Gallery, anti-aesthetic projects articulated in the vicinity of the arte povera language, translate personal experience into a political discourse about the limits that new national mythologies have inscribed on individuals.

Queer identity became his main research focus as his first works exhibited in Timișoara. As his activist activity intensified within the Timişoara association LGBTeam, Sorin Oncu began to build installations from found objects, which were ascribed different meanings and contexts. He explored more experimental territories, videos, animations, found assemblages or assemblages built out of the most whimsical materials. His artistic practice claimed itself from a school of thought which was completely absent in Romania. In Romania, more than anywhere in Central and Eastern Europe, homosexuality remained criminalized until 2001, and the feminist movement began timidly as a drooping periphery of the academic discourse. It truly began to infiltrate the academic space only post-1990. The effects of the interdictions practiced in national-communist Romania, closed by the “iron curtain”, are very visible until today, including in the conservative discourses that still dominate the cultural space. Sorin Oncu challenges all the myth-making structures that underpin discrimination, offering to the audience the experience of their own alterity. The series Identity (2005), Coming Out (2006), Antihomophobic (2006-2013) include manifestations of his own sexuality labelled as “deviant”.

At the queer art group exhibitions opened in Bucharest during the LGBT History Month, Sorin Oncu proposed critical works on the dominating system, ironically reporting the Romanian reality. At OTA in 2012, he exhibited an installation that questioned the absence of the term “homophobe” in the Explanatory Dictionary of Romanian Language. The vehement, political discourse is packed in a poetic art, solved in controlled anti-aesthetic forms. Through this brief, but intense activity, Sorin Oncu opened several debates that remain to this day of major importance in the national culture. More than 15 years after the decriminalization of homosexuality, before a gay movement succeeded in shaping and asserting itself in the Romanian space, a citizens’ initiative puts in the official monitor the intention to redefine marriage in Article 48 of the Constitution. Within this context, the continuation of Sorin Oncu’s activity by studying and exhibiting his art becomes more than a need for knowledge, an important political gesture at a time of crisis.

Translated by Roxana Ghiță.

1. Rosi Braindotii, The Posthuman, Hecate Publishing House, 2016, p. 75.

The Visual Artists’ Union of Romania (U.A.P) Awards 2016

The Visual Artists’ Union of Romania Awards Gala represents a good opportunity to designate excellence in contemporary visual arts and to reward the efforts of Romanian artists with outstanding work in 2016. It is the moment when we can highlight the performance of a segment of contemporary culture that is increasingly active on the Romanian and international scene. The magnitude of the visual phenomenon entitles us to look with great confidence to this rather marginalized field in our culture.

We capitalize this year also on the support of the Ministry of Culture and National Identity, thus being able to ensure the continuity of the project and the consolidation of the tradition. We hope that in the near future we will be able to resize this format by including it in a broader program – a National Exhibition of Contemporary Art, following the model of the Interwar Saloons, organized under the high patronage of the Ministry of Culture.

At the same time, we hope to materialize the promises of the Ministry regarding the furtherance of a package of laws that will help to strengthen the artist’s regulations, to create an adequate National Contemporary Art Fund, to stimulate creativity and to fit up museums with a valuable contemporary art fund.

With an appropriate normative framework and an effort undertaken by the authorities to treasure up contemporary art, the quality and dynamics of artistic life would increase significantly. The artist would benefit from a favourable work environment, entering into a cultural dialogue inside the fellowship and feeling appreciated. The public could get into a deeper contact with the contemporary art phenomenon. Art collectors would have a wider range of credible offers, the museum being a space of consecration. The art investment is a sustainable one. All the people involved would simply gain.

Professor Petru Lucaci, PhD

President of Visual Artists‘ Union of Romania

Director of Revista ARTA

Changing Museums

Here is an exciting topic: museums are trendy! Museums are vertically growing! Museums are in transition and changing! It has become evident that in recent decades there has been a spectacular growth in the number and variety of museums around the world. Museum sciences and practices have greatly diversified, and the relationship of the museum with the public and the community has changed radically.

Under the influence of liberal thinking and aggressive neo-capitalism, museums have been rapidly changing their philosophy and practice, and their functions are subject to a profound change in the classic conservation / research / communication ratio. From a typical institution of cultural modernism, the museum has to adapt to a postmodern world in frenetic globalization. From the 1970s to the present, various definitions of the museum, more or less adapted, which have aimed to embrace novel concepts of education and entertainment, cultural policies adapted to societal changes have emerged, increasingly diverse and “immaterial” patrimonies have been created, strong practices focused on democratic relations with increasingly differentiated audiences have been implemented.

Located today at the ambiguous intersection between pragmatic and cultural, between commerce and communication, between the mass public and the elite, the museum is summoned to reinvent itself again. Subject to a market logic, becoming an increasingly “spectacular temple”, the museum is forced to adapt to the Internet, social networks and the digital age in which we have entered, but also to preserve its formative and identity formation role. Being the centre of diverse human communities, the museum must take on a role of socialization and conviviality. In a post-capitalist world of globalization, museums must therefore “produce democracy” without neglecting their standards. Here are some ideas gathered from a vast problematic ocean tackled by numerous specialists and commentators.

Is this moment of major change positive or negative for museums? How do Romanian and foreign museums react to these radical challenges of the present? How do artists, curators, art critics and theorists position themselves regarding these current themes? You will learn about all these important aspects in this issue, coordinated by the museum curators Valentina Iancu and Mălina Ionescu.

Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-chief

Translated from Romanian by Roxana Ghiţă

Hundred Year-Old Dada

One hundred years after its outbreak in Zürich, is Dada still a hot up to date topic for a strictly contemporary visual arts magazine like ARTA? Is Dada still a viable combustible, radical state of mind or a still-productive artistic movement? Well, yes, da. Da, da. DaDa. Re-discussed with last year’s centenary, celebrated on the Romanian scene with an ample exhibition at Art Safari Bucharest, but celebrated in fact all around the world, dada remains a provocative and stubborn catalyst of 20th century modern art. This issue’s special section, coordinated by art historian and curator Igor Mocanu, retackles and demonstrates – with the help of renowned specialists from Romania and abroad – a few important theses. Firstly, that Dada represented a trigger for many important visual avant-garde movements, both pre- and post-war, from surrealism to Fluxus, Lettrism, Situationism, happening, Neo-Dada, and others. Then, the belonging of many avant-garde artists, Dadaists included, to the “cultural international” of European Judaism, marked by a syncretic, internalizing logic, especially in the central and eastern parts of the continent. Then there’s the fact that Dada was and remains – perhaps more than we’d like to admit – a defining ingredient for both modern and postmodern Romanian cultural identity. Herein lies the importance of the Romanian component – through Tristan Tzara, Marcel Iancu and his two brothers, Iuliu and George, Arthur Segal, and others – in the field of international academic studies dedicated to the movement. Finally, this issue manages to prove beyond doubt – through the influence in the art of young Romanian and foreign visual artists – that Dada still emanates an exceptional creative fertility which, in spite of a hundred years, will not deplete too soon, because in it lies the indefinite possibility of evolution through insubordination and contradiction.

Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-Chief

Hybrids – art from inside the cyclone

With this issue, Revista ARTA attempts an experiment – perhaps a risky one – regarding both the theme and the design. To discuss hybrids, hybridisation, hybridity in the current status of the Romanian art scene, as young curator & art critic Cristina Bogdan, our coordinator, proposes, does not lack showiness, perhaps courage, certainly an amount of danger. Hybridity may seem like an umbrella term for contemporary art, a notion both obvious and difficult to refine in its conceptual ramifications and its psychological, cultural and social effects. Hybridity defines the ecclectic mix of artistic techniques and genres, the suprising articulation of modes of action and aesthetic theoretisation, as well as the ingenious blending of cultural & non-cultural codes and references which the artistic production of the past 10 years has made us witness. A practice embraced by the radical wing of the new generation of artists and critics from Romania and elsewhere, hybridisation refers to a programmatic and fluid transgression of the various aesthetic barriers left standing after modernisms and postmodernisms, to a productive mix between abstract discourse and relational and sociologic gestures in art, in order to invent possible evolution scenarios. It highlights the dominance of super-conceptual artistic actions which chose the amalgam of natural, artifical and virtual to put forth provocative means of questioning the world in socio-political terms. Finally, hybridity announces an ambiguous paradigm change in the contemporary art world, towards an apparent dilution within an immanent philosophy of “art without art”, aiming to rescue the efficiency and relevance of the artistic in a world seen as increasingly relativised and banal, ruled by financial capital. And yet a new, fascinating world.

The texts in this issue of Revista ARTA will inform you, in a highly theoretical style and a language which is itself new, about singularities and performativity, about the destabilising and desirable collision between mediums and disciplines, about Esthetic Entities coming from the future and works which address, modify or create their own conditions of existence, about alienating strategies, about the political & creative hacking of existing codes – in a word, about the need of contemporary art to configure its “own form of hybridity, between the conceptual and the aesthetic”. You will also learn about concepts, actions and projects (additivist litterature, Second Artworld, Second Body, Dead Thinking, Eternal Feeding, End Dream, Black Hyperbox, Postspectacle, institutional hybridity, etc.) of specific artists and groups, in Romania and elsewhere, for whom this practice is symptomatic.

In an artistic world with many cultural speeds – polarised between generations, urban centres and various artistic groups, working on one hand with leftovers of modernism and postmodernism, attempting on the other hand new fluid and ambiguous forms of integrating an immediate reality, non-representable with traditional artistic means, part of a global socio-political problematics – to discuss such artistic phenomena, apparently marginal but in fact situated right at the centre of the cyclone, becomes not a risk, but a duty. Or rather, a commitment.

Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-chief

Graphic arts, a necessary reconsideration

The dossier of this issue of Revista ARTA is part of those which our editorial team dedicates to various visual disciplines, be they traditional or recent, with the aim to offer a concentrate but symptomatic panorama of the state of visual arts in Romania and, if possible, in our geographical neighbourhood. Although multivalent by its numerous classical techniques, graphic art seems not to have got the status it deserves, i.e. of major art, in spite of the fact that the innovations brought about by the techno-sciences and the predominance of the visual in all forms of communication should push us to reconsider it.

But this Revista ARTA dossier, coordinated by Ciprian Ciuclea, himself a multidisciplinary graphic artist, does not speak about the relation between graphic arts and advertising, mass-media or internet. It is more like a quick review of what graphic art meant for the Romanian scene before and after 1989, with its artists, exhibitions, and places that defined its territory. It is even more about what has happened with graphic arts in the last twenty years, within the present-day civilization dynamism, wherein a continuous redefinition of concepts, techniques, and problematics takes place, as well as a permanent hybridization with other forms of artistic action, and a contamination with multimedia and informational technology. All these characteristics place graphic arts under the sign of a generalized experimental mentality, which assumes uncertain, haphazard, and virtual visual formulas, an opening towards the social and the politics, as well as a post cultural condition in the attempt to vividly capture the enormous pulse of our contradictory, ever changing reality.

Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-chief

Conceptualism in Eastern and Central Europe

This issue is dedicated to a theme that has been expected for a long time now: conceptualism in the Romanian and East-European visual arts. This trend which appeared in the West in the context of the reevaluation of classic modernism during the post-war neo-avant-gardes of the 1960s has become a sort of compulsory aesthetic paradigm in the last decades. More and more inclusive and diluted, conceptualism deserves an applied and exigent analysis nowadays. Set under the sign of an intransigent purism coming from Duchamp’s provocation from the beginning of the last century, but also influenced by the intellectual debates of the 1960s, conceptualism has reduced the artwork and the artistic action to their rational, logic, idea-centered essence – an essence “freed” of the traditional elements of “sensoriality”, expressivity, affective resonance, cultural symbolism etc. Nevertheless, in contact with the historical texture of each cultural space, conceptualism has arrived progressively to mix with numerous local influences which have given very different, even contradictory, colors to its content. The capacity of conceptualism to radically deconstruct ideological, linguistic, or visual mechanisms has transformed it into a favorite instrument of the most interesting East-European visual artists in their resistance against the political system. The file of this issue of Revista ARTA – coordinated by art critic and theoretician Cristian Nae – intents to demonstrate with the help of several brilliant texts signed by well-known Romanian and East-European commentators, how conceptualism has evolved in this cultural area towards a more hybrid and impure formula – but a formula which is succulent and very charged semantically (and politically). This is a way of transforming the disadvantage of a marginalized geo-strategic position and cultural provincialism into an advantage rooted in an incredible, even exceptional, cultural and spiritual richness.

Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-chief

The true value of certain awards

Let us tell the truth: the force and quality of contemporary visual arts in Romania do not have the visibility and recognition they deserve in the local public space. In a culture traditionally centered on literature, and recently more oriented towards the spectacular-performing arts which attract a large public, visual arts are a sort of Cinderella that has to demonstrate all the time its value and utility. Nevertheless, starting with Brâncuși in the past and up to Adrian Ghenie in the present, the most famous and expensive artists of Romanian origin were (and are) visual artists. Moreover, the vitality of the young visual scene in Bucharest and in other Romanian cities is astonishing and very promising, although little reflected in the mass-media.

That is why we are dedicating the thematic file of the issue no.19 of Revista ARTA to the 2015 Awards of the Union of Visual Artists of Romania (UAP). Resumed after eight years, with the help of the Ministry of Culture, these awards represent a sign of normality in a convulsive socio-political reality. These sixteen awards were conferred to well-established artists belonging to different visual domains, but also to several gifted young artists, and they all deserve our recognition.

We also wish to believe that these awards demonstrate a new interest of the authorities for an artistic field which was deprived of correct institutional support and funding so far. But, beyond recognition and respect, Romanian visual culture needs much more, in fact: a National Fund for contemporary art, created by annual acquisitions of art works, and a big International Biennial of visual arts in Bucharest, supported by the same Ministry of Culture, would be the two projects that could render to the visual arts their true importance.

Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-chief

The cultural value of sound

Maybe visual artists and the public at large will be astonished to notice that the current issue of Revista ARTA is tackling a topic such as sound art – and not a strictly visual topic. But in our times of trans-mediality, where all sensorial combinations and techno-artistic hybridizations are possible, getting closer to the sound space in which we are all immersed becomes not only obvious, but necessary. We need to become more conscious of the countless forms of soundscape to which we have access and which model us unconsciously, not only because the present-day visual and curatorial practices have used for decades now the relationship with sound in installations, video art, performances etc, but because sounds have become an essential, even overwhelming dimension of our lives, just as much as the visual dimension. We live not only in a unchained civilization of the visual, but also in a civilization of sounds, noises, sonorities, music that is increasingly mixed, sophisticated and all-pervasive. That is why we need a culture of the sonorous identity of our contemporary existence – with its democracy, facilitations, excesses and dangers – as much as we need a culture of the visual, which has in fact entered earlier in our common habits. Taking the pretext of the Sound Week in Bucharest from March 2016, the thematic file of this issue of Revista ARTA proposes, under the coordination of Anamaria Pravicencu and Octav Avramescu, a fascinating incursion into the territories of sound art, radio art, radio theater, visual-sonorous installations of all kinds, for a forceful initiation in the culture of hearing. This culture is important not only for musicians, sound engineers, film producers, ecologists, psychologists or anthropologists, but also for visual artists and visual specialists – since sound is, paradoxically, a key-element for our visual perception. And sound creation is an important part of the complex multisensory performance in which we live continuously, not only in the white cube of art galleries and museums, but also in our everyday life.

Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-chief

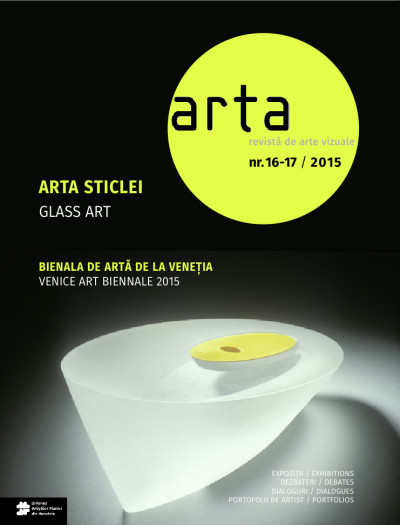

Glass Art

Following the dossier dedicated to contemporary ceramics in the issue no.13 of Revista ARTA, it became obvious, even necessary to us o propose a dossier dedicated to contemporary art glass in this double issue 16-17 of our magazine. Bearing a vertiginous process of emancipation from the strict domain of an applied, “decorative” occupation, art glass is heading nowadays in a spectacular manner towards major approaches, proving its conceptual and expressive capacities in such areas as the sculptural, the monumental, ambient, installation. Through its diverse techniques, more and more sophisticated – blown glass, modeled at warmth, glass produced through fusion and baking, optical crystal etc – today’s art glass is adding new experimental and scientific parameters to its traditional expressivity related to light, transparency, and unpredictability. Coordinated by art critic Aurelia Mocanu, the dossier we are proposing in this issue is offering a symptomatic radiography through the present-day state of this difficult and fragile art, by questioning well-known glass artists, from Romania and abroad, and by trying to take the pulse of the domain’s international state through a series of theoretical, more general texts.

The Venice Biennial 2015

The second dossier of this issue, aiming at reviewing the recently closed Venice Biennial of visual arts, is coordinated by art critic Daria Ghiu. The 56th edition of Venice Biennale is discussed in our pages by curators, gallerists, and art commentators, from Romania and abroad, such as Mihai Pop, Edit Andras, Diana Ursan, Eleonora Farina, Gabor Andrasi a.o. The accent is set on the two Romanian participations in this edition: Darwin’s Room, by Adrian Ghenie, curator Mihai Pop, at the Romanian Pavilion – and Inventing the Truth. On Reality and Fiction, a group exhibition curated by Diana Marincu at the Romanian Institute for Culture and Humanistic Research in Venice. This second exhibition showed young artists such as Michele Bressan, Carmen Dobre-Hametner, Alex Mirutziu, Lea Rasovszky, Ștefan Sava, and Larisa Sitar. The conclusion of the analyses and comments are encouraging: the existence of two „national” projects create the possibility of a dual presentation, which offers a expanded and more nuanced perspective on what contemporary Romanian art “which matters internationally” means.

Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-chief

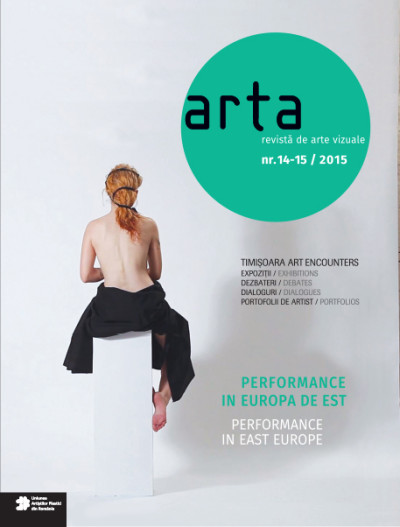

Performance Art is Alive

Performance art is not dead, as some people would like to have it! This is the good news brought by the main dossier of this double issue of Revista ARTA. Under such names as happening, processual or performative art, situationist or contextual art, actionism or corporal / body art, performance art has remained since the 1960s maybe the most direct, incisive, and cutting-edge form of artistic expression of the last decades. Positioned at the cross-point between the visual, the discursive, and the theatrical, involving the artist with his/her entire physical, psychological, and spiritual being, in front of the public or together with it, performance art has not yet run out of resources in the context of the last years, when other forms of visual intervention have become more fashionable. Since the 1960s, performance art has represented a form of protest of the artists against the aesthetic establishment, accelerated muzeification, and the consumerism of the art market. The dossier coordinated by Ileana Pintilie demonstrates all these assertions, but also underlines the emancipating dimension performance art has had in the former communist countries of Eastern Europe – the fascination and fear which totalitarian regimes developed in front of this provocative form of social and artistic non-conformism.

Art Encounters Biennial

The second dossier of this issue, coordinated by Sorina Jecza and dedicated to the recently closed Art Encounters Biennale of Timisoara, sheds some light on the resurgence of a large and important city into the more and more dynamic and competitive field of visual arts in Romania. Taking place in multiple locations, highlighting non-conventional spaces, and reaching social communities very little involved in such cultural actions so far, the Art Encounters Biennale – under the direction of the two main curators, Nathalie Hoyos and Rainald Schumacher – was a success. Under the title “Appearance and Essence”, this biennale proposed not only a concentrated image of the most original, individual and collective, visual projects of Romania’s last decades. It was also a demonstration of the capacity of present-day Romanian visual artists to integrate, with their own specificity, the global artistic network.

Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-chief

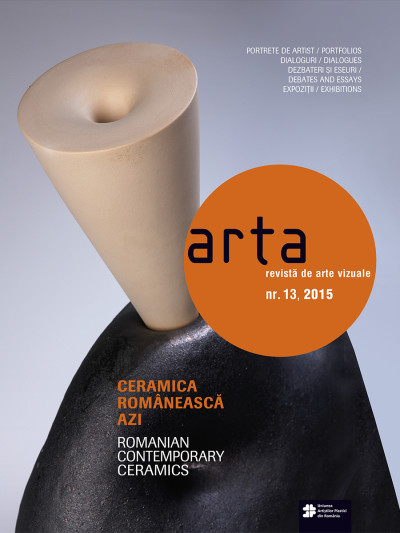

I think the moment has come for Revista ARTA to dedicate a consistent thematic file to one of the most dynamic arts in the present-day Romanian visual world. Ceramics has been for some time now in an alert process of demarginalization, of leaving behind its traditional retirement and discretion to get in the middle of today’s formal battles. There is nowadays a more and more offensive and wide-spread consciousness that the decorative can represent, in all its forms of expression, a major artistic exercise, a visual research as complex, elaborate and open towards superior senses as any other modality of practicing the artistic impulse.

From the traditional pole to the avangardist one, new practical procedures have explosively dynamized this ancient art of fire: digital technologies, mixed-media, multimedia, 3D printing, but also “author’s techniques” invented by the artists themselves for new materials and chemical processes. All this confers to the domain of ceramics an active experimental dimension, extremely diversified and personalized.

The freedom to try everything, interdisciplinarity, the transfer between artistic techniques and visual currents be they modern or postmodern, have explosively marked this art of the clay, sandstone, and porcelain. In its field one can notice nowadays the existence of such tendencies as conceptual or historicist ceramics, installation and sculptural ceramics, experimentalist and cultural quotation ceramics etc, combined in the most diverse and inventive manners. The present-day impetuosity of ceramics is proved as well by the fact that it is practiced – as an art of interior or as an art of public spaces, with assumed social dimensions – by more and more artists coming from unexpected domains of action.

The current emancipation of ceramics at an international level – evident in the number of biennials and big exhibitions, in specialized art magazines and art fairs, but also in the global professional community sustained by blogs and social networks on internet – this emancipation is equally obvious at our local level. The special file of this issue of Revista ARTA wants to demonstrate that Romanian ceramists have now a more intense consciousness of their possibilities of a major creation and cultural recognition and that Romanian ceramics can and wants to play a more visible role in our society.

Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-chief

This issue’s thematic dossier is something quite new in comparison with the usual format of Revista ARTA. After previous issues dedicated to visual genres (painting, sculpture, photography, urban art), to local schools of painting (the Cluj school of grey, the 1980s generation), to movements like postmodernism and feminism, or to international events like the Venice Biennale, we thought it might be interesting, and even useful, to open the pages of our magazine to the international art milieu, in order to allow a better knowledge, in Romanian, of some prestigious and influential national art scenes.

And what could be more tempting nowadays than British art, with its creative spirit, so unleashed and provocative, and its competitive taste, so courageous and dangerous? The world of visual arts in London remains for the time being – as the famous City district for the financials – a sort of Mecca of our domain, to which lots of artists, gallery owners, dealers and curators from all parts of the world are constantly attracted, whether they are established or beginners. Are not the universities of London the most coveted in the world, towards which a river of students of all nationalities flow in haste every year ? From the YBA (Young British Artists) generation, from the 1980s up to the present, the language of visual and commercial radicalism in art is the Londonian, the same way as the lingua franca of today is and remains English.

We owe to our young collaborator Cristina Bogdan, Lecturer in Art Theory in London, this extremely interesting thematic dossier about the British art world, with its ups and downs, wherefrom many Romanians will have something to learn, be they artists, professors, curators, critics, historians, or gallery owners. Produced with personal efforts and without any sponsorship from a British institution, the file can be an extremely useful instrument for either a young aspirant, to prepare him or her for the British utopias and sirens, or for a mature person, to comfort him or her from the illusions of a place too much dreamed of not to hide in it the warning of a famous Latin formula: Hic sunt leones!

Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-Chief

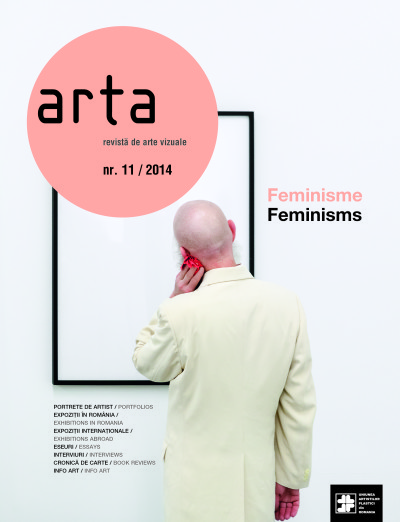

Consistent with its initial program to scan those themes that seem stringent to our artistic actuality, ARTA tackles now the area of feminisms in the Romanian and Central-East-European visual region, and partially in the Western world. We speak of feminisms in the plural as after the combative and politically engaged feminism of the 1970s, what followed was a more and more diversified and nuanced deployment of a multitude of debates on social, cultural, regional, post-colonial and national issues, carried on within the central topic of gender and sexual politics of the paradigmatic feminism.

In the dossier of Revista ARTA, coordinated by art critic and curator Olivia Nițiș, a first set of texts debates on theoretical aspects of feminist trends in the Anglo-Saxon world, wherefrom feminism has started, and in the Central-Eastern European world where we live. A series of texts follows that recuperate the history of feminist attitudes – not very numerous, but substantial – in the Romanian visual arts of the last twenty years. At last, a final section of the dossier sheds light on recent and alternative r/evolutions to the feminist mainstream, which take into account queer, ecologist and leftist positions of the young generation.

Without being exhaustive, this issue of Revista ARTA intends to give the pulse of a cultural and artistic phenomenon which becomes more and more visible in Romania. After the pioneering issue of Artelier art magazine in 1999/2000 devoted to the same theme, this issue no.11 of Revista ARTA confirms, at 15 years of distance, the vitality of a domain of reflection which, without being central in the local debate of ideas, has contributed a lot to the humanist and aesthetical refinement of our present-day sensitivity and to the integration of Romanian visual production into a large international context.

Magda Carneci, Editor-in-chief

It was probably inevitable for us to dedicate the special dossier of this issue of Revista ARTA to the Venice Biennale of this year. Obviously, because it is the most important event of this kind in the global visual world, but also because the theme of this 55th edition was simultaneously fascinating and intriguing. Under the title “Encyclopedic Palace”, we witnessed a selection of artists și artworks which seems to go against the general visual trend of today, marked by so much (post) conceptualism, sociologism / (eco) relationism, and a pragmatic formalism with commercial undertones.

On the contrary, what we could see in Venice this year was an inverse selection so to say: artworks and attitudes which are envisioning an impossibility – the visual image tempting an integral figuration (and trans-figuration) of the world, an Imago Mundi, the effort of certain artistic (and non artistic) brains to catch through visual forms those elements often invisible (as being subconscious or superconscious) which are structuring our coherent understanding of reality. The selection of this Venice Biennale privileged, after a long time of absence, those visual poetics that are focalized on the subtle relationship of the self with the world, the dialogue of the profound psyche with the universe: in other words, those visual discourses obsessed mostly with the “inner image”, so important for our good psychic evolution and so badly overwhelmed by the huge diluvium of external images in which we are living.

Artistic as much as anthropologic, spiritual as much as ethnographic, poetic and scientific, “passeist” and futurist, imaginative and visionary, The Venice Biennale of 2013 has meant a challenge for our recent visual habits. The special dossier of this issue of Revista ARTA – coordinated by Diana Marincu and Anca Mihuleț – has addressed this challenge in texts signed by contributors from Romania and abroad, who take into discussion also several national pavilions, among which the Romanian one which was very successful.

Magda Carneci, Editor-in-chief

How do sculptors understand themselves and how is sculpture perceived on the cultural scene of today’s Romania ? Even if marked by the aesthetic transformations of the last more than twenty years as any other visual genre, sculpture seems a little bit out of the public attention, if it is not about monuments of a debatable taste ordered by the political power in place. More determined by its material conditioning and by its apparently “atemporal” link to space, sculpture seems to have developed a tortuous, even tensioned relation cu modernism and postmodernism. Nevertheless, after the years 1965-1989, a period which gave several important names to this medium, Romanian sculpture has evolved and transformed itself constantly, and new names and provocative formulae have appeared, of which this issue of Revista ARTA intends to offer testimony.

In the first chapter of the issue, the texts of the dossier coordinated by Adriana Oprea set themselves intentionally under a more restrained, “implosive” definition, that of modernist sculpture and of its continuation up to the present by several new and strong names. In the second chapter, this perspective is completed by an enlarged, “expanded” definition of sculpture, in the sense given by Rosalind Krauss to this sintagm. An art inquiry sums up the opinions of twelve Romanian sculptors about their production in the last more than twenty years; to this the answers of several sculptors of Romanian origin living abroad are added. The “explosive” sense of contemporary sculpture is also illustrated by several examples of Romanian art galleries focused on sculptures and by several examples of curatorial projects that tackle new ways, more circumstantial and temporary, of placing sculptural objects in the public space.

Even if it only re-opens the taste for an artistic medium which is more disvantaged than others by the economic and political crises of today, I thing this issue of Revista ARTA proves, even if succintly, that sculpture remains a major genre in the contemporary art of Brancusi s original country.

Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-chief

This issue on photography intends to offer a possible synthetic image of the multiple ways in which this dominant, even ”imperialistic,” medium is understood and utilized in nowaday’s Romanian art. After six years from a previous collective volume dedicated to this subject, Revista ARTA invited the best-known Romanian visual artists, critics, and curators who dealt with photography, to collaborate in this issue, consistent from many points of view. The two coordinators of the issue – Iosif Király and Simona Dumitriu – have conceived a transversal section through a very arborescent domain: from the presentation of the departments of photography within the main universities of art in Romania to the pre- and post-1989 history of this medium in the local visual arts; from projects of well-known artists to projects of still young and student artists; from essays and theorical texts on photography to the analysis of the modalities in which this medium has been used in the interdisciplinary research. If we add to all this the interviews, the exhibition reviews, the reviews of books of art, and the art inquiery, all of them mostly dedicated to the same common denominator of the issue – we hope the image proposed by Revista ARTA of the complex way photography dominates and permeates the present-day Romanian visual scene becomes consistent and credible.

Magda Carneci, Editor-in-chief

This issue’s theme was born from an obvious observation. Even though it reached the age of consecration, the 80s generation of visual arts doesn’t have the same public recognition (or knowing) like that of literature, which generated the (disputed) concept of the literary eighties. Although it produced concepts of its own like the “neo-expressionism” or the “intermedialism”, along with the famous and controversial “postmodernism”, the 80s generation of visual arts doesn’t seem to be a “front” as coherent and compact as its literary counterpart.

In the post-communist upheaval of the 90s and in the economic boom of the 2000s, the visual eighties artists placed themselves in between the mature generation that kept control over several levers of institutional power, and the young and very young generations that knew the privilege of new foundations, centers, galleries and curators that showed up in the meantime, either in the country or abroad, always looking for “alternative art”.

As opposed to their literary brothers who had a sufficiently abundant exegesis and a sort of “classification” in these last 20 years, all because literature was predominant in the Romanian cultural field, the eighties practitioners of visual art had to make due in difficult work conditions and make up inconvenient and atypical professional trajectories, oscillating between working within the country and working abroad, all this while having the most unusual side jobs. This is why the fulfilment of their art is less evident. It is true that the eighties artists had a small appetite for public life. They appeared to be marked by a psychology of marginalization, perhaps coming from behavioral reflexes inherited from before 1989. Even though they were hard working and productive, assuming discreet roles on the institutional stage while building solid careers, the way the visual eighties artists were seen suffered, not cause of the coming together of their own works, but because of the wide cultural reception of their art. And still, the 80s generation of visual arts has a few big names, some of which known abroad, that deserve to be recognized by the wider audience, at least as much as the literary artists. Here are some of these artists in no particular order: Dan Perjovschi, Ioana Bătrânu, Iosif Kiraly, Marilena Preda-Sânc, Dan Mihălţianu, Mircea Roman, Călin Dan, Miklos Onuscan, Petru Lucaci, Romelo Pervolovici, Marian Zidaru, Gheorghe Rasovszky, Ion Aurel Mureşan, Christian Paraschiv, Ștefan Râmniceanu, Alexandru Păsat, Vioara Bara, Rudolf Bone, Alexandru Antik, Marcel Lupșe and other that are present in the pages of this issue.

The file dedicated to the eighties generation “revisited” after 20 years was coordinated by Magda Cârneci and Adrian Guță, two of its critics and theorist that published books on this matter. The list of artists in this issue is not comprehensive, overlooking names of painters (Gheorghe Ilea, Mihai Chioaru, Andrei Chintilă, etc), sculptor (Vlad Aurel, Mircea Popescu, etc), graphic artists (Mircea Stănescu, Dorel Găină, Gheorghe Urdea, etc) and decorative artists (Daniela Făiniș, Titu Toncian, Ilie Rusu, Simona Tănăsescu, Mihai Țopescu, etc), that we hope to present in future issues. It remains to be seen whether this approach to make a compact presentation of the eighties artists will offer the public a sufficiently coherent image of “the visual eighties” and if it will be an incentive, a dare even towards newness, evolution, or if this is the beginning of a “classicization”.

Magda Cârneci, Editor-in-chief

The revival of painting?

There was a lot of hesitation amongst the editorial staff about the title for the main theme for this double issue of ARTA. Should we call it the Neo New Painting of today? The New Photo-Realism or The New Figurative? Should we call it The New Honesty, The Neo Pop-Socialism or The Revival of Painting since the 2000s? All of these possible (and questionable) labels only partially cover an obvious phenomenon that has been going on in the Romanian art scene in the last decade. We are witnessing an amazing, enormous, even viral comeback of this reign of visual art in its classic signification as painting.

The turbulent 90s that were so bewildered by the invasion of new artistic techniques and the sudden openness to internal and international contradictory aesthetic ideologies appeared to be placed, at least in the most visible part of the Romanian art scene, under the menacing threat of “the death of painting” as a major way of visual molding and aesthetical marking of reality. As opposed to the irruption of installation and performance art, of photography and video art as fast and dynamic formulas for implementing the artistic gesture in the concerning now, practicing painting seemed a traditional and repetitive occupation, incapable of visual freshness and technical anachronism – someone once said “whoever painted during those years was stupid” (Mihai Pop). The political urgencies of that moment, the need to rapidly adapt to anticommunism activity and to pro-capitalist ideologies, the rivalry between the new mediums, they all seemed to permanently invalidate painting’s capacity to say something profound about the new human condition and to adapt to the new world the arose in Romania. This occurred everywhere in Eastern Europe because of the difficult overlapping of a tenaciously viral post-communism and a new liberal ferociousness.

Still, painting survived in the depths of the studios for this “crossing of the transitional desert” even though it appeared to be killing painting in the public interest’s eyes. During the late 90s and especially in the mid 2000s there was a gradual and spectacular revival that placed painting back in cultural interest. The Rostopasca Group, a series of symptomatic exhibitions in the capital and in other cities, The School of Grays in Cluj, the Bucharest Neo-pop, these are just some of the marks belonging to this intense and overflowing phenomenon, of which you will find consistent and very interesting texts in this double issue of ARTA.